What is in this Leaflet

The information in this leaflet will answer some of the questions you may have about PRAVACHOL. This leaflet does not tell you everything about the medicine.

Your doctor and pharmacist have been provided with full information and can answer any questions you may have.

This leaflet is no substitute for talking with your doctor or pharmacist. You should follow all advice from your doctor when being treated with this medicine.

Ask your doctor or pharmacist if you have any concerns about taking this medicine.

You should read this leaflet carefully before starting PRAVACHOL and keep it in a safe place to refer to later.

What is it used for

PRAVACHOL is used to treat people who have had a heart attack or an episode of unstable angina, or who have high blood cholesterol levels. In these people PRAVACHOL can reduce the risk of further heart disease, reduce the possibility of needing a bypass operation, or reduce the risk of having a stroke.

It lowers high blood cholesterol levels (Doctors call this hypercholesterolaemia). It is also used if your cholesterol levels are normal if you have had a heart attack or an episode of unstable angina.

It is used to treat heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia in children and adolescent patients aged 8 years and older as an adjunct to diet and lifestyle changes.

If you have had a heart attack, an episode of unstable angina or you have too much cholesterol in your blood, then you have an increased risk of a blood clot forming in your blood vessels and causing a blockage. Blood vessels that become blocked in this way can lead to further heart disease, angina or stroke.

PRAVACHOL may be used to lower lipids in heart or kidney transplant patients, who are also being given immunosuppressive medicine.

It is used to treat long-term (chronic) conditions so it is important that you take your PRAVACHOL every day.

It is not addictive or habit forming.

It is only available upon prescription from your doctor.

How does it work

PRAVACHOL tablets contain pravastatin sodium, a drug that reduces the level of cholesterol in your blood and helps to protect you in other ways from heart attack or stroke. It is more effective if it is taken with a diet low in fat.

Before I take it

Before taking PRAVACHOL, you should be aware of the following:

You should not take it

- if you are or may become pregnant

- if you are breast feeding

- if you have ever had an allergic reaction to pravastatin sodium or any other ingredient listed at the end of this leaflet

- if you have ever had liver disease

- if you have had muscle pain from any other medicine used to treat high cholesterol

Do not give your medicine to any one else even if they have the same condition as you have.

Before you take it

You must tell your doctor if:

- you are taking other medicines or treatment

- you drink alcohol regularly

- you have ever had liver problems

- you have a problem with your kidneys

- you are or may become pregnant

- you are breastfeeding

- you suffer from hormonal disorders

- you suffer from central nervous system vascular lesions

- you suffer from allergies

- you suffer from homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia, (a doctor will have told you this)

- you have increased triglycerides in your blood (a doctor will have told you this also)

- you suffer from muscle disease (including pain, tenderness or weakness).

Taking other medicines

Some medicines can affect the way PRAVACHOL works.

You should always tell your doctor about any other medicines you take, even those bought without a doctor's prescription.

It is especially important that you tell your doctor if you are taking any of the following:

- any other medicine to lower cholesterol

- cyclosporin

- ketoconazole

- spironolactone

- cimetidine

- gemfibrozil

- cholestyramine and colestipol

- antacids

- Macrolides

- Propanol

- Bile acid sequestrants

- Digoxin

- Warfarin or other Coumarin anticoagulants

Please discuss any of these with your doctor if you need to take any of them.

It generally does not interfere with your ability to drive or operate machinery. However some people may experience dizziness, so you should be sure how you react to PRAVACHOL before you drive a car, or operate machinery.

How to take it

How much to take

PRAVACHOL should only be used as directed by your doctor. Your doctor will decide on the dose, this will depend on many factors including your cholesterol level. The dose for lowering cholesterol is 10 – 80mg, and is 40mg for reducing the possibility of a stroke or heart attack.

The recommended dose is 20 mg once daily for children 8 – 13 years of age and 40 mg once daily in adolescents 14 – 18 years of age, with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia.

How to take it

Take PRAVACHOL once a day in the evening before bed-time.

For best results, take PRAVACHOL on an empty stomach (ie. two or more hours after your last meal).

Take PRAVACHOL at about the same time each day. Taking it at the same time each day will have the best effect and will also help you remember when to take it.

If you forget to take it

If you forget to take a dose of PRAVACHOL, take the next dose normally at your usual time.

Side Effects

All medicines, including PRAVACHOL, can sometimes cause unwanted effects. This is not an exhaustive list.

The most common side effects are:

- upset stomach

- nausea

- diarrhoea

- wind

- constipation

- headache

- dizziness.

Tell your doctor as soon as possible if you have any of these side effects or any other problem while taking PRAVACHOL.

Your doctor may arrange blood tests.

You must tell your doctor immediately, or go to the hospital, if you suffer any of the following:

- unexplained muscle pain

- tenderness

- weakness.

It is also possible to suffer from an allergic reaction to PRAVACHOL, so tell your doctor if you develop a skin rash or itchiness, fever, joint pain or shortness of breath.

In few cases, statins have been reported to induce de novo or aggravate pre-existing myasthenia gravis or ocular myasthenia.

If you take too much (Overdose)

Call your doctor immediately if you or someone else has taken too much PRAVACHOL.

If your doctor is not available call your nearest hospital or a Poisons Information Centre on 13 11 26.

Storage

Store PRAVACHOL in a cool dry place, and keep the tablets in the blister until it is time to take them.

Store PRAVACHOL below 25°C, and protect from light and moisture.

The expiry date is printed on the pack. Do not take it after the expiry date or if the tablets have changed in appearance colour or taste.

Ask your pharmacist about disposal of unused tablets.

Keep all medicines out of reach of children.

Product description

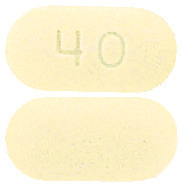

What it looks like

Pravachol 10mg tablet - engraved ‘10’. AUST R 68706

Pravachol 20mg tablet - engraved ‘20’. AUST R 68704

Pravachol 40mg tablet - engraved ‘40’. AUST R 58075

Pravachol 80mg tablet - engraved ‘80’. AUST R 101491

Pravachol tablets are yellow capsule shaped tablets supplied in blister packs containing 30 tablets per pack.

Active ingredients

Pravachol 10mg tablets - 10mg pravastatin sodium

Pravachol 20mg tablets - 20mg pravastatin sodium

Pravachol 40mg tablets - 40mg pravastatin sodium

Pravachol 80mg tablets - 80mg pravastatin sodium

Inactive ingredients

PRAVACHOL tablets also contain lactose, povidone, microcrystalline cellulose, croscarmellose sodium, magnesium stearate, magnesium oxide and iron oxide-yellow.

Contains sugars as lactose.

Sponsor & Distributor

Arrow Pharma Pty Ltd

15 – 17 Chapel Street

Cremorne Victoria 3121

This leaflet was revised in October 2023.

Published by MIMS December 2023

There was no statistically significant difference in the change in lens opacity between the control and pravastatin treatment groups during this time interval.

There was no statistically significant difference in the change in lens opacity between the control and pravastatin treatment groups during this time interval. In a pooled analysis of two multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia, treatment with pravastatin at a daily dose of 80 mg increased HDL-C and significantly decreased total-C, LDL-C and TG from baseline after 6 weeks. The efficacy results of the individual studies were consistent with the pooled data. Mean percent changes from baseline after 6 weeks of treatment were: total-C (-27%), LDL-C (-37%), HDL-C (+3%) and TG (-19%), with placebo subtracted changes for LDL-C and TG of -36% and -20% respectively.

In a pooled analysis of two multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia, treatment with pravastatin at a daily dose of 80 mg increased HDL-C and significantly decreased total-C, LDL-C and TG from baseline after 6 weeks. The efficacy results of the individual studies were consistent with the pooled data. Mean percent changes from baseline after 6 weeks of treatment were: total-C (-27%), LDL-C (-37%), HDL-C (+3%) and TG (-19%), with placebo subtracted changes for LDL-C and TG of -36% and -20% respectively. The effect on the combined endpoint of coronary heart disease death or nonfatal myocardial infarction was evident as early as six months after beginning pravastatin therapy.

The effect on the combined endpoint of coronary heart disease death or nonfatal myocardial infarction was evident as early as six months after beginning pravastatin therapy.

In the Long-term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) study, the effect of pravastatin 40 mg daily was assessed in 9014 men and women with normal to elevated serum cholesterol levels (baseline total-C = 4.0-7.0 mmol/L; mean total-C = 5.66 mmol/L; mean total-C/HDL-C ratio = 5.9), and who had experienced either a myocardial infarction or had been hospitalised for unstable angina pectoris in the preceding 3-36 months. Patients with a wide range of baseline levels of triglycerides were included (≤ 5.0 mmol/L) and enrolment was not restricted by baseline levels of HDL cholesterol. At baseline, 82% of patients were receiving aspirin, 76% were receiving antihypertensive medication, and 41% had undergone myocardial revascularisation. Patients in this multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled study participated for a mean of 5.6 years (median = 5.9 years). Treatment with pravastatin significantly reduced the risk for CHD death by 24% (p = 0.0004). The risk for coronary events (either CHD death or nonfatal MI) was significantly reduced by 24% (p < 0.0001) in the pravastatin treated patients. The risk for fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction was reduced by 29% (p < 0.0001). Pravastatin reduced both the risk for total mortality by 23% (p < 0.0001) and cardiovascular mortality by 25% (p < 0.0001). The risk for undergoing myocardial revascularisation procedures (coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty) was significantly reduced by 20% (p < 0.0001) in the pravastatin treated patients. Pravastatin also significantly reduced the risk for stroke by 19% (p = 0.0477). Treatment with pravastatin significantly reduced the number of days of hospitalisation per 100 person years of follow-up by 15% (p < 0.001). The prespecified subgroup (age, sex, hypertensives, diabetics, smokers, lipid subgroups) analyses were conducted using the combined endpoint of CHD and nonfatal MI. The study was not powered to examine results within each subgroup but formal testing for heterogeneity of treatment effect was undertaken across each of the subgroups and no significant heterogeneity was found (p ≥ 0.08), i.e. a consistent treatment effect was seen with pravastatin therapy across all patient subgroups and event parameters. Among patients who qualified with a history of myocardial infarction, pravastatin significantly reduced the risk for total mortality by 25% (p = 0.0016); for CHD mortality by 23% (p = 0.004); for CHD events by 22% (p = 0.002) and for fatal or nonfatal MI by 25% (p = 0.0008). Among patients who qualified with a history of hospitalisation for unstable angina pectoris, pravastatin significantly reduced the risk for total mortality by 26% (p = 0.0035); for CHD mortality by 26% (p = 0.0358); for CHD events by 29% (p = 0.0001) and for fatal or nonfatal MI by 37% (p = 0.0003). See Table 7.

In the Long-term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) study, the effect of pravastatin 40 mg daily was assessed in 9014 men and women with normal to elevated serum cholesterol levels (baseline total-C = 4.0-7.0 mmol/L; mean total-C = 5.66 mmol/L; mean total-C/HDL-C ratio = 5.9), and who had experienced either a myocardial infarction or had been hospitalised for unstable angina pectoris in the preceding 3-36 months. Patients with a wide range of baseline levels of triglycerides were included (≤ 5.0 mmol/L) and enrolment was not restricted by baseline levels of HDL cholesterol. At baseline, 82% of patients were receiving aspirin, 76% were receiving antihypertensive medication, and 41% had undergone myocardial revascularisation. Patients in this multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled study participated for a mean of 5.6 years (median = 5.9 years). Treatment with pravastatin significantly reduced the risk for CHD death by 24% (p = 0.0004). The risk for coronary events (either CHD death or nonfatal MI) was significantly reduced by 24% (p < 0.0001) in the pravastatin treated patients. The risk for fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction was reduced by 29% (p < 0.0001). Pravastatin reduced both the risk for total mortality by 23% (p < 0.0001) and cardiovascular mortality by 25% (p < 0.0001). The risk for undergoing myocardial revascularisation procedures (coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty) was significantly reduced by 20% (p < 0.0001) in the pravastatin treated patients. Pravastatin also significantly reduced the risk for stroke by 19% (p = 0.0477). Treatment with pravastatin significantly reduced the number of days of hospitalisation per 100 person years of follow-up by 15% (p < 0.001). The prespecified subgroup (age, sex, hypertensives, diabetics, smokers, lipid subgroups) analyses were conducted using the combined endpoint of CHD and nonfatal MI. The study was not powered to examine results within each subgroup but formal testing for heterogeneity of treatment effect was undertaken across each of the subgroups and no significant heterogeneity was found (p ≥ 0.08), i.e. a consistent treatment effect was seen with pravastatin therapy across all patient subgroups and event parameters. Among patients who qualified with a history of myocardial infarction, pravastatin significantly reduced the risk for total mortality by 25% (p = 0.0016); for CHD mortality by 23% (p = 0.004); for CHD events by 22% (p = 0.002) and for fatal or nonfatal MI by 25% (p = 0.0008). Among patients who qualified with a history of hospitalisation for unstable angina pectoris, pravastatin significantly reduced the risk for total mortality by 26% (p = 0.0035); for CHD mortality by 26% (p = 0.0358); for CHD events by 29% (p = 0.0001) and for fatal or nonfatal MI by 37% (p = 0.0003). See Table 7.

The safety and efficacy of pravastatin doses above 40 mg daily have not been studied in children. The long-term efficacy of pravastatin therapy in childhood to reduce morbidity and mortality in adulthood has not been established.

The safety and efficacy of pravastatin doses above 40 mg daily have not been studied in children. The long-term efficacy of pravastatin therapy in childhood to reduce morbidity and mortality in adulthood has not been established.