Mild asthma: practical considerations and a new treatment option

Managing asthma is an interplay of practical considerations, shared decision-making and treatment guidelines. We discuss what to consider when navigating treatment options for mild asthma, including the new reliever option of low-dose budesonide + formoterol.

Key points

- Recent changes to asthma guidelines aim to improve treatment of mild asthma for adults and adolescents

- As-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol is now PBS-listed as a reliever option for people with mild asthma

- Most adults and adolescents with asthma are now advised to start with either a regular daily maintenance low-dose ICS plus SABA as needed, or as-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol as their only treatment

- Regular review, shared decision-making, and patient education are essential to selecting the most appropriate treatment and improving health outcomes for people with asthma

Mild asthma is common, however severe flare-ups (also known as exacerbations) among this population make up 30%–40% of emergency presentations.2

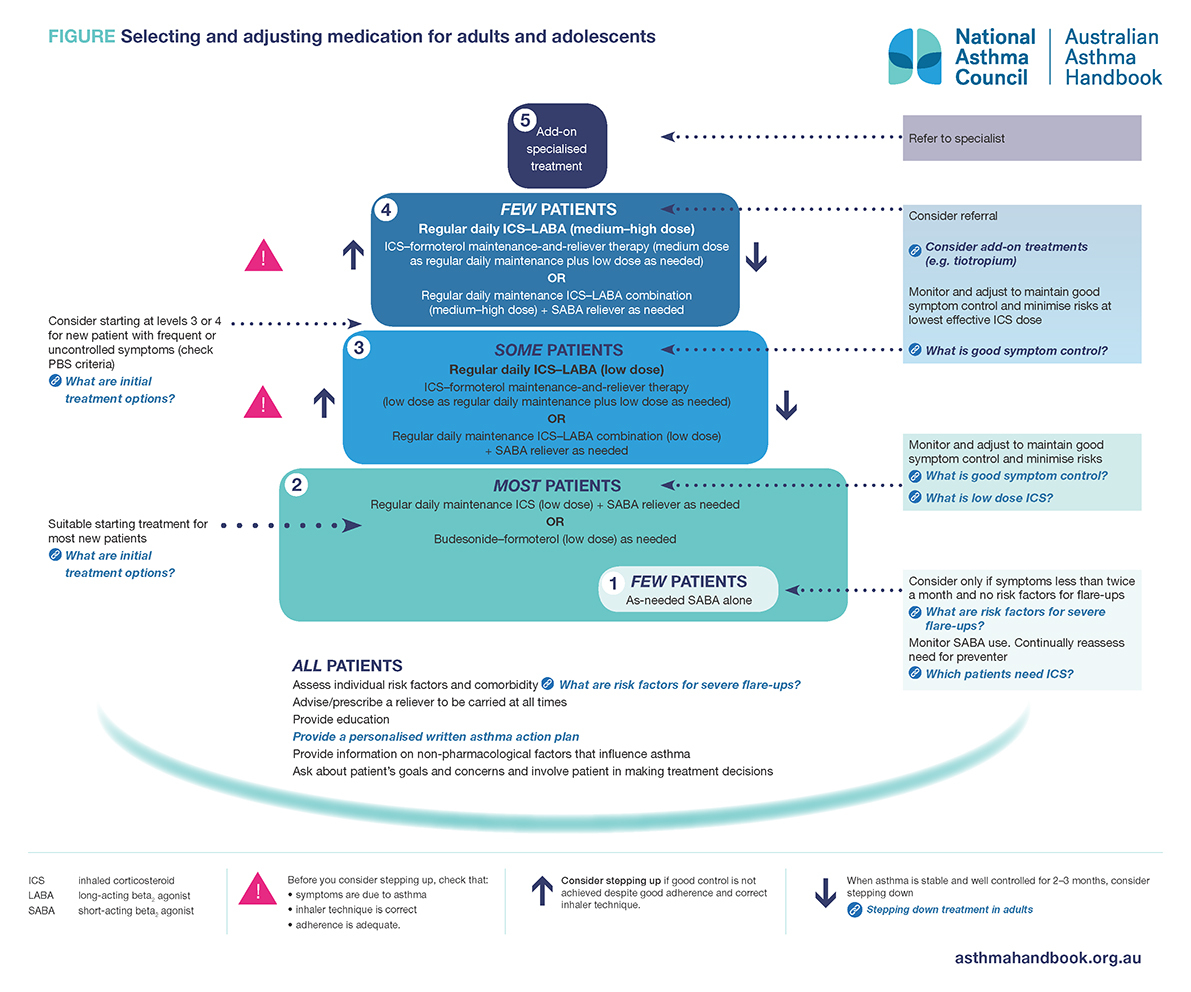

Inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) inhalers are the most effective preventer medicines for asthma. This means that people with mild asthma will experience few or no symptoms when their asthma is well controlled by Step 1 or 2 treatment (as seen in Figure 1).3,4

In 2020, the treatment options at step 2 changed to include the option of as-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol.4

Active management is important for people with mild asthma

A person’s level of asthma control and risk factors can help determine whether there should be a stepping up or stepping down of asthma management.4

Evidence from clinical trials shows that most adults with asthma will benefit from using ICS as part of their asthma management, as ICS inhalers are the most effective preventer medicine for asthma. This can be achieved by using regular maintenance ICS or as-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol.4

Patients with infrequent symptoms or who do not have risk factors for flare-ups (and do not meet the criteria for routine ICS treatment) may still receive treatment with ICS.4

Additionally, only a few patients should be receiving treatment with a SABA only (patients who meet all the criteria for step 1 in table 1 below). Increased use of SABA for symptom relief, especially daily use, indicates worsening of asthma control.4 This is discussed in more detail below.

Table 1: Australian Asthma Handbook guidelines for initial treatment choices for mild asthma4

|

Severity |

Suggested management |

|

Step 1a For patients who:

Patients with newly diagnosed asthma in primary care often do not meet these criteria. |

SABA reliever aloneb |

|

Step 2 For patients who:

*Note: The patient must not be only using as-needed SABA, must be monitored frequently and could be considered for specialist referral |

Regular daily maintenance ICS (low dose) plus SABA reliever as needed OR Budesonide + formoterol (low dose) as needed |

a this refers to few patients.5

b As of August 2020, terbutaline (Bricanyl Turbuhaler) is only PBS-listed for people who are unable to coordinate use of MDI to deliver SABA or are unable to use another SABA due to a clinically important adverse event during treatment.4

What is the new treatment option?

As-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol has now been approved by the TGA as an alternative to maintenance low-dose ICS.4 It is PBS-listed for patients with mild asthma who need anti-inflammatory reliever therapy and who are not on concomitant LABA therapy.6

The new listing includes:7

- budesonide 200 micrograms + formoterol fumarate dihydrate 6 micrograms per dose, 120 doses (Symbicort Turbuhaler 200/6 for 12 years and over; DuoResp Spiromax for 18 years and over).

- budesonide 100 micrograms + formoterol fumarate dihydrate 3 micrograms per dose, 120 doses (Symbicort Rapihaler 100/3 for 12 years and over).

See the PBS website for more details.

For a person who needs preventer treatment for asthma but does not take a regular low-dose ICS (either by choice or due to suboptimal adherence), the combination of the ICS and formoterol ensures rapid bronchodilation when symptoms occur, as well as delivery of anti-inflammatory medicine to address the underlying inflammation. Additionally, using this combination as a reliever will result in the person receiving more regular ICS.4

NB: this is not the Symbicort Maintenance and Reliever Therapy (SMART) regimen. Use of as-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol by people with mild asthma is not a maintenance and reliever therapy as it is only indicated for use as a reliever alone. SMART is not considered until Step 3 and 4 of the treatment algorithm developed by the National Asthma Council (see Figure 1), while as-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol for mild asthma is a treatment option at Step 2.4

Reproduced with permission, from Australian Asthma Handbook, version 2.1. © National Asthma Council Australia 2020, accessed 27 October 2020.

Read an accessible version of the information in this figure

What’s the evidence?

The Symbicort Given as Needed in Mild Asthma (SYGMA) 1 and 2 trials looked at the use of as-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol for people with mild asthma.

SYGMA 1 found that as-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol provided superior control of asthma symptoms when compared to as-needed terbutaline. However, it was inferior to budesonide maintenance therapy.8

SYGMA 2 found that as-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol was non-inferior to twice-daily budesonide maintenance therapy in terms of rate of severe asthma flare-ups, but was inferior in controlling symptoms.9

As-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol was the only treatment option studied in the SYGMA trials, as other ICS + LABA combinations were not included.8,9

Managing asthma: involve the individual

SDM improves health outcomes for people with asthma. A Cochrane review found that patient education, regular medical review, self-monitoring and use of a written action plan supported improved health outcomes compared to usual medical care.11

It has also been demonstrated that patients with poorly controlled asthma achieved better adherence to their asthma medicines when shared decision-making about their treatment was incorporated into management, compared to usual care (no asthma care management). As a result, these patients had better asthma-related quality of life, fewer asthma-related medical visits, reduced use of reliever medicines, better controlled asthma and lung function compared to patients receiving usual care.12

Through SDM the clinician can explore what a patient understands about their asthma, what their management goals are and what their ability is to self-manage (using a personalised asthma action plan). This can help to minimise the impact of asthma on quality of life, optimise symptom control and reduce flare-ups and potential adverse medicine effects.4

Practical considerations to discuss with patients

Managing a person’s asthma involves several practical considerations (Table 2). A longer appointment may be required to allow sufficient time to cover these and other points for discussion (see What else should I discuss with patients?).

Table 2: Practical considerations for the management of asthma

|

Considerations |

Points for discussion |

|

Cost Discuss the cost of as-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol compared to SABA relievers or a maintenance ICS inhaler plus SABA when required. The patient may also worry about the cost of ongoing medical appointments. |

“Many people buy [Ventolin] every few months or even monthly. On an annual basis, the cost of Symbicort used as-needed may be less than relying on OTC salbutamol.” – Debbie Rigby For most people, 80%–90% of the benefit of ICS is obtained with low doses when used correctly. Better control means less risk of flare-ups and less need for other medicines.13 People with asthma can save costs by using their inhaler correctly. Good inhaler technique means less medicine wastage and more medicine reaching the airways.13 For people with mild intermittent asthma, as-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol is more effective than a SABA reliever for a range of clinical parameters. This may allow people to save money in the long run, if they are using SABA relievers frequently. Reinforcing the long-term benefits may help to address the barrier of cost.14 For more information, see the Australian Prescriber article ‘The cost of asthma medicines’. This article discusses how ICS, when used correctly, can reduce treatment costs. |

|

Diagnosis and treatment |

Provide the patient, and their family and other carers, with information to help them manage their asthma in partnership with their health professionals. This should include information about their asthma diagnosis, the rationale for treatment, and how relievers differ from preventers’.3 Patients should also understand the differences between the roles of ICS and SABA in asthma management (ie, that SABAs help symptom relief by relaxing bronchial smooth muscle, while ICS for maintenance treatment reduce airway inflammation and bronchial hyperactivity).10 “The conversation about ‘relievers’ and ‘preventers’, the reason they are labelled as such and the correct way to use them, is always useful. The pathophysiology of an exacerbation; inflammation, mucus overproduction and smooth muscle spasm and the way medications effect the process is useful information. Giving ‘both barrels’ and explaining that inflammation benefits from ICS and there is less scarring of the airways and thus over time far less reduction in overall lung function can sway some doubters.” – Dr Ian Almond |

|

Perception of risk Patients may not feel they need to consider changing their regimen to include regular ICS if they have mild asthma.15 |

One study that looked at Australian data reported that 15%–20% of adults who died from asthma experienced symptoms less than weekly in the preceding 3 months.16 As most adults with asthma will benefit from ICS treatment, using the as-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol inhaler is an enabler and may be more appealing for some people compared to using a daily maintenance inhaler.4 “For people just relying on Ventolin for symptom control, especially OTC use without a regular check-up by their GP, we can talk about the benefits of not only helping their immediate symptoms, but also impacting on the underlying inflammation in the lungs and reducing the risk of a severe exacerbation.” – Debbie Rigby1 |

|

Inhaler technique Most people with asthma do not use their inhalers properly and also have not had their inhaler device technique checked.4 |

When selecting the most appropriate treatment option, consider patient preferences for devices and their ability to achieve good inhaler technique. Ensure they are taught correct technique and this is reviewed regularly.3 A standardised checklist to monitor and correct inhaler technique can help improve asthma control for adults.3 Factors to consider include mishandling of devices (such as failing to clean the spacer, or allowing the mouthpiece of DPIs to become blocked), and using an empty or expired inhaler.4 See the NPS MedicineWise inhaler technique device-specific checklist. |

|

Adherence Poor adherence can result from having trouble with the inhaler, the regimen (including using multiple inhalers) or misunderstanding instructions. It may also be intentional if the person does not feel the treatment is necessary.3 |

Adherence to preventer medicines may be a concern, especially when someone is only experiencing mild or infrequent symptom and may not feel the need to take a regular preventer.4 Adherence is significantly improved when people are given the opportunity to negotiate the treatment regimen, based on their personal goals and preferences.4 For people having difficulty using their medicines correctly (particularly those taking multiple medicines), it may be helpful to refer them to an asthma educator, or for a MedsCheck by a community pharmacist, or Home Medicines Review by an accredited pharmacist (if eligible).4 Another enabler for adherence is the NPS MedicineWise app. This can be used to set up medicine reminders. |

|

Side effects People with asthma may worry about adverse effects from using asthma medicines, such as oral candidiasis and dysphonia from use of ICS.3 |

Most people using asthma medicines do not experience adverse effects. The risk of adverse effects increases with higher doses of asthma medicines and incorrect inhaler technique.3 For people prescribed pMDIs, a spacer can improve delivery and reduce the potential for local adverse effects from ICS.4 For people using ICS, the risk of candidiasis can be reduced by rinsing the mouth and spitting out after use.3 Note that this step is not necessary for people using as-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol as reliever therapy.4 |

|

Follow-up and review If good control of a patient’s asthma symptoms can’t be achieved, referral and further assessment may be required to re-confirm the diagnosis or investigate other causes. |

Consider using questionnaire-based tools to help review control of asthma symptoms.4 Asthma control questionnaires are available from the Australian Asthma Handbook website. If a diagnosis cannot be made with confidence from clinical features, spirometry testing and response to treatment, consider further investigation and referral to appropriate specialists (such a respiratory or general physician).4 Referral may also be considered if signs and symptoms do not respond to a treatment trial, or if work-related asthma is suspected (eg, referral to a respiratory physician, occupational physician and/or allergist with experience in work-related asthma).4 “It is important to provide a formal follow-up appointment, especially if there are concerns or there has been a change of treatment.” Dr Ian Almond, GP and member of the National Asthma Council Guidelines Committee |

What else should I discuss with patients?

As-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol as reliever therapy

This reliever replaces their previous SABA reliever, which should only be used in an emergency if their own reliever is not accessible. Even though formoterol is a LABA, it has a rapid onset of action with bronchodilator activity within 1–3 minutes.10

Budesonide + formoterol may also be used before exercise for exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Before exercise, the person should take one standard dose (one inhalation of budesonide 200 micrograms + formoterol 6 micrograms via DPI, or 2 puffs of budesonide 100 micrograms + formoterol 3 micrograms via pMDI). This should be noted on their written asthma action plan.4 Note that these medicines are not PBS-listed for the treatment of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in the absence of asthma.7

What if symptoms worsen?

People using as-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol as a reliever, without a daily maintenance preventer, may take extra doses if their symptoms worsen or do not improve a few minutes after initial use.4 The information in table 3 should be included in their personalised written asthma action plan.

Table 3: When patients may need medical attention based on their usage of as-needed low-dose budesonide + formoterol4

|

Metered-dose inhaler (Symbicort Rapihaler 100/3) |

Dry-powder inhaler (Symbicort Turbuhaler 200/6, DuoResp Spiromax 200/6) |

|

More than 12 inhalations per day for more than 2–3 days:

|

More than 6 inhalations per day for more than 2–3 days:

|

|

More than 24 inhalations needed in one day:

Keep taking more doses as needed while waiting. |

More than 12 inhalations needed in one day:

Keep taking more doses as needed while waiting. |

Overuse of SABA – why do we need to be careful?

“The overuse of SABA and increased risks of serious exacerbations which do not respond should be emphasised [to patients]” – Dr Ian Almond

Patients with well-controlled asthma will not need to use their SABA reliever on more than 2 days per week (excluding doses taken for preventing exercise-induced bronchoconstriction). Increased use of SABA relievers for asthma symptoms, especially daily use, suggests worsening asthma control.4

The risk of severe flare-ups is increased for patients using only SABA relievers, without ICS (or with poor adherence to ICS). High doses of SABA do increase the risk of asthma flare-ups. Regular continued use of SABA can lead to receptor tolerance to their bronchoprotective and bronchodilator effects, which could result in a poor response to emergency treatment for severe asthma.4

Patients should also be aware that frequent use of SABA relievers may be a sign of poorly controlled asthma and could potentially increase their risk of asthma flare-ups.4 Patients who have been dispensed more than three SABA inhalers in a year (average 1.6 puffs per day) have an increased risk of flare-ups. Those who have been dispensed 12 or SABA inhalers in a year (average 6.6 puffs per day) have an increased risk of death from asthma.4

“The SABA is doing nothing for the underlying inflammation. Yes, it’s helping with the symptoms due to bronchoconstriction, but it’s doing nothing for the inflammation.” - Debbie Rigby.14

Despite this, salbutamol still plays an important role in treating acute asthma (which can be classified as mild-moderate, severe or life-threatening). Salbutamol should be given immediately to patients with severe or life-threatening acute asthma and in some cases may need to be given through a nebuliser. (Note that nebulisers have a high risk of transmitting viral infections by generation of aerosol droplets that can spread for several metres and remain airborne for over 30 minutes).4

Written asthma action plan for adults

People with asthma should have a personalised written asthma action plan, which should be updated regularly (at least once a year and whenever their treatment changes).4

Further information

Tools and resources to support health professionals

- NPS MedicineWise webinar: New asthma guidelines

- COVID-19 and asthma: Australian Asthma Handbook

- National Asthma Council Australia health professional resources

- Asthma Australia health professional resources

Educational resources for patients

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the experts who contributed to this MedicineWise News.

Dr Ian Almond is a general practitioner in Tasmania and a member of the National Asthma Council Handbook Committee.

Rebecca Edwards is a consumer advisor who has been working with Consumers Health Forum for over 10 years.

Debbie Rigby is an advanced practice pharmacist with postgraduate qualifications in clinical pharmacy, geriatrics and respiratory medicine. She is a certified asthma educator.

References

- Paola S. Combination inhaler PBS listed for mild asthma. Chatswood, NSW: Australian Journal of Pharmacy, 2020 (accessed 23 September 2020).

- Dusser D, Montani D, Chanez P, et al. Mild asthma: an expert review on epidemiology, clinical characteristics and treatment recommendations. Allergy 2007;62:591-604.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. USA: GINA, 2020 (accessed 22 September 2020).

- National Asthma Council Australia. Australian Asthma Handbook, Version 2.1. Melbourne: National Asthma Council Australia, 2020 (accessed 22 September 2020).

- National Asthma Council Australia. Preview to Australian Asthma Handbook V2.1 released. South Melbourne: NAC Australia, 2020 (accessed 23 September 2020).

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Budesonide + formoterol (eformoterol). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2020 (accessed 24 September 2020).

- NPS MedicineWise. RADAR: Budesonide with formoterol for mild asthma: New PBS listings. Sydney: NPS MedicineWise, 2020 (accessed 24 September 2020).

- O'Byrne PM, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, et al. Inhaled combined budesonide-formoterol as needed in mild asthma. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1865-76.

- Bateman ED, Reddel HK, O'Byrne PM, et al. As-needed budesonide-formoterol versus maintenance budesonide in mild asthma. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1877-87.

- Australian Medicines Handbook. Respiratory drugs. Adelaide: AMH Pty Ltd, 2020 (accessed 30 September 2020).

- Powell H, Gibson PG. Options for self-management education for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003:CD004107.

- Wilson SR, Strub P, Buist AS, et al. Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;181:566-77.

- Reddel HK, Lembke K, Zwar NJ. The cost of asthma medicines. Aust Prescr 2018;41:34-6.

- Paola S. Symbicort now registered for mild asthma. Chatswood, NSW: Australian Journal of Pharmacy, 2019 (accessed 23 September 2020).

- Lewin E. New paper discusses barriers to optimal asthma management. Sydney: RACGP, 2019 (accessed 22 September 2020).

- Reddel HK, Busse WW, Pedersen S, et al. Should recommendations about starting inhaled corticosteroid treatment for mild asthma be based on symptom frequency: a post-hoc efficacy analysis of the START study. Lancet 2017;389:157-66.