There is a range of interventions that can reduce the risk of falls. A multidisciplinary approach may be helpful.

Review the regimen

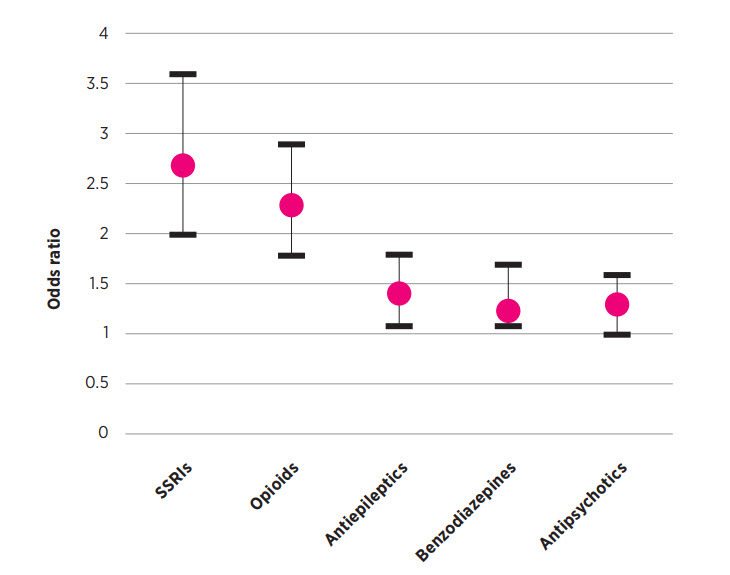

Reviewing and modifying older people’s medicines to align with their preferences, expectations, treatment goals and level of function is good practice.20 Gradual withdrawal of psychotropic drugs can reduce falls.1 When considering which drugs to taper or cease, prioritise them based on their risk and the patient’s needs, as well as the ease of dose reduction or cessation, and the availability of safer alternatives. It may be necessary to consult with other prescribers and discuss the options and potential outcomes with the patient.20 If deprescribing, stop one drug at a time and wean doses slowly over weeks or months while closely monitoring the patient for benefits or adverse effects.20 Stopping too quickly can cause withdrawal syndromes.

Avoid starting an antidepressant for mild to moderate depression. Psychological management alone is appropriate first-line treatment.21 For older patients with full resolution of symptoms, consider tapering and ceasing SSRIs. (To find out how to taper and cease an antidepressant, go to The Veterans' MATES Depression management therapeutic brief or Australian Prescriber's Switching and stopping antidepressants.)

For older patients taking an opioid for chronic pain, consider a multidisciplinary approach to help them understand why pain can persist even after an injury has healed and how active self-management strategies can help them overcome their pain.22 Review the use of opioids and, where possible, slowly taper and cease or substitute with a non-opioid analgesic as the patient’s ability to regain control and self-manage increases. (To find out how to taper and cease an opioid, go to The Veterans' MATES Understanding chronic pain therapeutic brief.)

In dementia, behavioural and psychological symptoms often fluctuate over time, and occur episodically, most commonly as a result of unmet physical or psychological needs combined with impairment of brain function, and lowered stress thresholds due to the disease process.23 If an antipsychotic is prescribed for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, limit the dose and duration and also consider the timing of the dose. When possible use non-pharmacological interventions.23 (To find out how to taper and cease an antipsychotic, go to The Veterans' MATES Dementia and changes in behaviour therapeutic brief.)

Avoid starting benzodiazepines in older patients. If a benzodiazepine is absolutely necessary, use for a short time only, at a low dose and monitor the patient closely.24 (For information on how to manage benzodiazepine dependence, and how to taper and cease, go to NPS MedicineWise's Managing benzodiazepine dependence in primary care.)

Discuss risk factors

Encourage patients to work with a range of health professionals to help them stay active and socially connected. Patients at high risk of falling include those who are visually impaired, have cognitive impairment, advanced diabetes or a neurological disease.1,25 Research suggests that multifactorial interventions that include individual assessment, group or home-based exercise programs, and home safety interventions are effective in helping to reduce falls.1

Explain to patients that some medicines can cause adverse effects that might increase their risk of falling. Encourage them to report any dizziness, drowsiness, confusion, or blurred vision. Ask them if they are willing to discuss possible changes to their treatment.

At least once a year and after changes to the treatment regimen, ask older patients if they ever feel unsteady on their feet or if they have fallen. Previous falls increase the risk of subsequent falls.25 Reassure patients that many things can be done to help prevent falls and to help them stay steady on their feet. A quick and simple falls-risk screen can identify patients who might be at risk of falling.25 This can be added to the template for a GP Management Plan and for health assessments in patients aged over 75 years.

Being involved in group or home-based exercise classes that focus on improving balance and building strength can reduce the risk of falls. It can also help to prevent injuries resulting from a fall.1

In Australia, one in four men and two in five women aged 50 years and over sustain a minimal trauma fracture, most commonly because of osteoporosis or osteopenia.26 Identify patients, without a history of a previous fracture, who are at high risk of poor bone health and refer them for a bone mineral density scan. There is a Medicare subsidy for bone mineral densitometry for people over 70 years who have not had a bone mineral density scan before and for younger people with specific risk factors for osteoporosis.27

Allied health interventions

Interventions by an occupational therapist to improve home safety can be effective particularly if the patient is at high risk of falling. (To find an occupational therapist, go to Occupational Therapy Australia.)

An assessment of foot pain by a podiatrist and advice about appropriate footwear, ankle and foot exercises, customised insoles and falls prevention strategies can help to reduce the risk of falling.1,25 DVA funds podiatry services for eligible DVA patients. (To find a podiatrist, go to the Australian Podiatry Association.)

Encourage patients to have their eyesight checked every two years or more often if needed.23 Remind patients that eye drops or eye ointment can cause blurred vision which can increase their risk of falling.