Article

Prescribing medicinal cannabis

- Jonathon C Arnold, Tamara Nation, Iain S McGregor

- First published 29 September 2020

- Aust Prescr 2020;43:152-9

- 1 October 2020

- DOI: 10.18773/austprescr.2020.052

Corrected 9 October 2020. View correction.

This is the corrected version of the article.

The Australian Federal Government legalised access to medicinal cannabis in 2016.

More than 100 different cannabis products are now available to prescribe. Most are oral preparations (oils) or capsules containing delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol or cannabidiol. Dried-flower products are also available.

As most products are unregistered drugs, prescribing requires approval under the Therapeutic Goods Administration Special Access Scheme-B or Authorised Prescriber Scheme.

Special Access Scheme Category B applications can be made online, with approval usually being given within 24–48 hours. However, supply chain problems may delay dispensing by the pharmacy.

By the end of 2019, over 28,000 prescribing approvals had been issued to patients, involving more than 1400 doctors, mostly GPs. More than 70,000 approvals are projected by the end of 2020.

Most prescriptions are for chronic non-cancer pain, anxiety, cancer-related symptoms, epilepsy and other neurological disorders. However, the evidence supporting some indications is limited.

Many doctors are cautious about prescribing cannabis. While serious adverse events are rare, there are legitimate concerns around driving, cognitive impairment and drug dependence with products containing delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Cannabidiol-only products pose fewer risks.

Legal access to medicinal cannabis products is now increasing. Many countries are relaxing their restrictions on cannabis in the face of escalating community interest, commercialisation of products and strong patient demand for access. The vast majority of Australians support access to medicinal cannabis.1 This support is galvanised by media stories of patients with intractable conditions whose lives have been transformed by cannabis-based medicines.2

The medical profession is understandably cautious around medicinal cannabis. A survey of Australian GPs reported that they felt uneducated around access pathways, available products and the evidence base supporting medicinal cannabis.3 Patient enquiries are common, yet only a small proportion of doctors feel comfortable discussing cannabis with their patients. Overall, GPs are positive about medicinal cannabis prescribing, given sufficient education, particularly for serious conditions such as cancer pain, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, epilepsy and difficult-to-treat neurological conditions.3 Specialist colleges and the Australian Medical Association remain conservative voices in the medicinal cannabis debate with concerns around the limited evidence from clinical trials and possible adverse effects.4,5

The cannabis plant contains hundreds of bioactive molecules, most of which are as yet uncharacterised. The two best studied cannabinoids are delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD).

THC is responsible for the intoxicating effects of cannabis due to its action on CB1 cannabinoid receptors.6 Despite intoxicating effects at higher doses, clinical trial evidence generally supports the efficacy of THC in treating conditions such as chronic pain, spasticity in multiple sclerosis, anorexia and cachexia, Tourette syndrome and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.7,8 Trials currently underway will help to better define the role of THC as a therapeutic across these and other conditions.9,10

CBD has a very wide range of pharmacological actions but no intoxicating effects. Early evidence suggests therapeutic actions of CBD at relatively high doses (300–1500 mg) in treating epilepsy, anxiety and psychosis.11-13 Numerous clinical trials are underway for other conditions such as neuropathic pain, drug and alcohol dependence and neurodegenerative disorders. In many countries, CBD is readily available in over-the-counter nutraceutical ‘wellness’ products. These contain very low doses (e.g. 5–25 mg) for which there is little current evidence of health benefits. Over-the-counter access to CBD is not yet available in Australia, although the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) is currently examining the possibility of such simplified access.14,15

Useful Australian websites on medicinal cannabis are listed in the Box.

Nabiximols (Sativex) is the only cannabis-based medicine currently listed on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods. It is an oromucosal spray containing THC and CBD in a 1:1 ratio and is approved for treating spasticity in multiple sclerosis. Another product, cannabidiol (Epidiolex), is a plant-derived oil-based formulation of CBD. It has recently been approved in the USA and Europe for the treatment of refractory childhood epilepsy, such as Dravet syndrome.11 The TGA is currently undertaking an expedited review process for registration of this product in Australia.

All other medicinal cannabis products available in Australia are unregistered medicines. Most of these are oral preparations, sprays or capsules of cannabis extracts with only a small fraction involving cannabis plant material such as the flower (intended for vaporisation). The products can contain THC only, CBD only or various ratios of CBD to THC. Around one-third of available products are CBD only.14,16 Trace levels of other cannabinoids and bioactive compounds (e.g. terpenes) may also be present.

Therapeutic doses of THC (5–20 mg) tend to be much lower than for CBD (e.g. 50–1500 mg). Many combined products therefore contain CBD:THC ratios of 10:1, 20:1 or 50:1.

Unregistered cannabis-based medicines are accessed through the TGA Special Access Scheme Category B (SAS-B) and the Authorised Prescriber Scheme. The vast majority are via SAS-B, although some prescribing also occurs through the Authorised Prescriber Scheme. The latter grants approval for a doctor to prescribe a specific product to a class of patients, rather than an individual patient (e.g. paediatric neurologists prescribing CBD products for children with refractory epilepsy).

SAS-B and Authorised Prescriber applications can be submitted without cost via the TGA’s website. The online portal has a single application which includes any additionally required applications for state and territory health departments, except for Tasmania (see Table). SAS-B applications are typically processed within two days if all the necessary information is provided. The vast majority of these are approved without modification.

Table - Australian state and territory requirements for prescribing Schedule 8 medicinal cannabis products

|

WA |

VIC |

NSW |

QLD |

TAS |

NT |

ACT |

SA |

||

|

Authorised |

General practitioner prescribing |

Yes* |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No† |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Documents required |

TGA online portal application |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

– |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

State Health application |

Done simultaneously via TGA online portal |

Done simultaneously via TGA online portal |

No – unless <16 years of age or a drug- dependent person |

No – unless a drug-dependent person |

– |

No – but required to notify the NT Chief Health Officer if the patient uses a Schedule 8 medicine for >8 weeks |

No – unless a drug-dependent person |

Yes‡ The patient can be put on a 2-month trial (and then health authority approval must be sought), if they are not on any other Schedule 8 medicine or drug dependent. |

|

|

Clinical justification and treatment plan |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

– |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Cannabis-based consent form |

No§ |

No§ |

No§ |

No§ |

– |

No§ |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Letter of support from specialist |

No*# |

No# |

No# |

No# |

– |

No# |

Yes |

No# |

* GPs in WA are required to seek specialist approval when prescribing to children under 16 years of age or to drug-dependent individuals.

† Only specialists can prescribe in Tasmania.

‡ Patients over 70 years of age or notified palliative care patients do not need a SA Health Schedule 8 approval.

§ Cannabis-based medicine consent forms are not required, but it is recommended to have one in the patient’s records.

# Unless a GP is applying to treat a condition outside of their area of expertise.

TGA Therapeutic Goods Administration

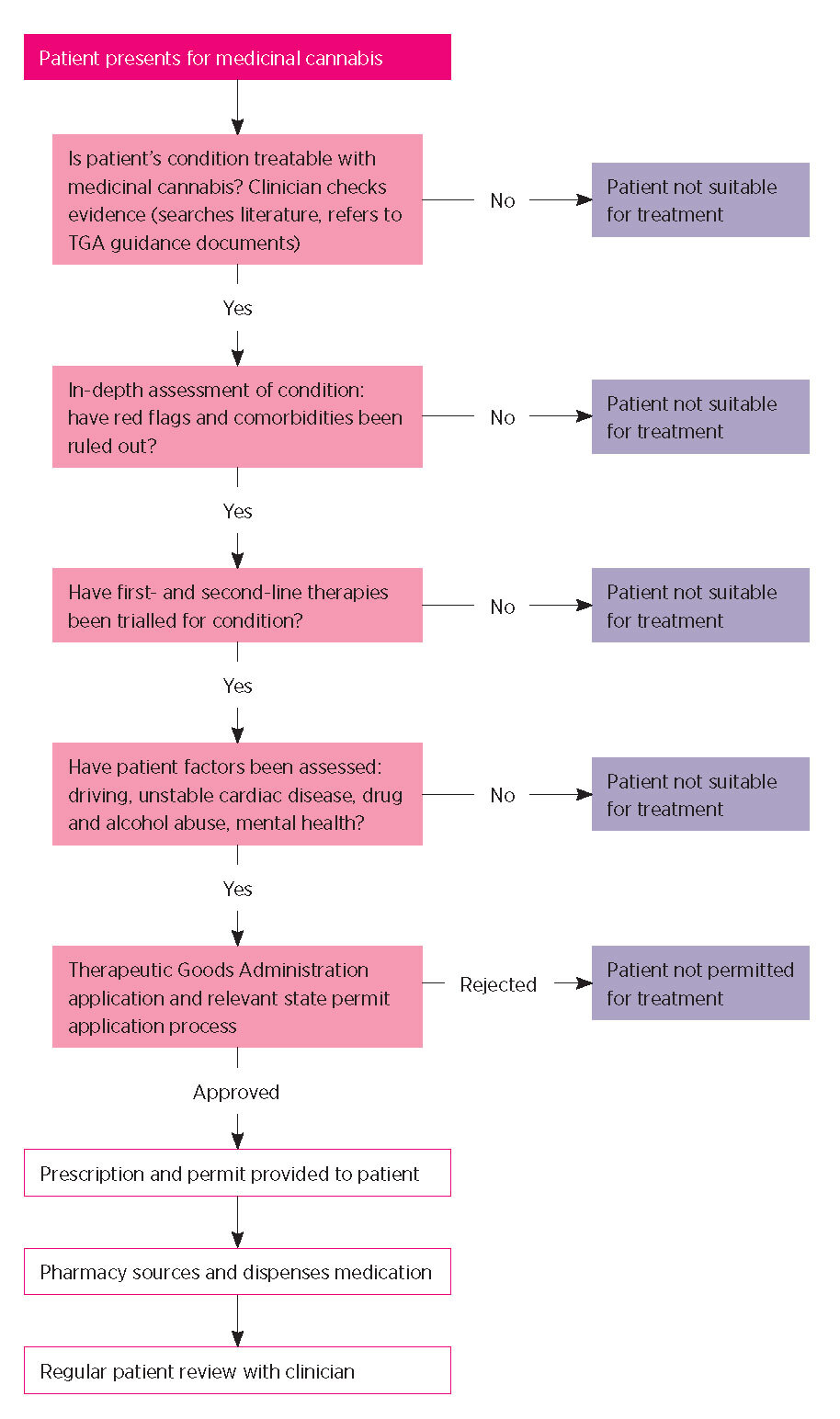

Generally, an SAS-B application must state the clinical justification for the use of a specific medicinal cannabis product for a particular patient. This includes the reasons for using an unregistered product rather than a registered medicine. Relevant safety and efficacy data and details of patient monitoring are required. There is also the option to attach any letters of support or recommendations from other treating specialists involved in a patient’s care. Prescribing doctors typically report that the first few SAS-B applications are time consuming but that the process rapidly becomes familiar and routine. The process for prescribing medicinal cannabis in Australia is outlined in Fig. 1.

By the end of 2019, more than 18,000 patients in Australia had accessed medicinal cannabis. This prescribing was by more than 1465 medical practitioners, mostly GPs.14 The number of approvals is rapidly increasing with a total of more than 28,000 individual applications approved as of 31 December 2019.14 As of June 2020, current approvals are running at around 4500 per month. The difference between the number of patients (18,000) and number of approvals (28,000) reflects repeat applications for the same patients – approvals are usually only provided for one year.

THC-containing products in Australia are included in Schedule 8 (controlled drugs). Prescriptions therefore require approval by a state or territory health department like other Schedule 8 medicines. The Table summarises the current requirements. Products that contain CBD only (at least 98% of total cannabinoid content) are Schedule 4 (prescription-only) medicines and do not require such approvals.

When prescribing for patients located in other states and territories, the prescriber must be mindful of meeting the Schedule 8 authorisation requirements of the location in which the product is dispensed. Tasmania has stringent additional requirements so there are few approvals in that state.14

Medicinal cannabis products are dispensed by pharmacies. It is critically important that the dispensing pharmacist has an understanding of the product and has clear lines of communication with the patient and prescriber. There is often a dose titration during the first weeks of therapy and this needs to be clearly communicated with the patient.

Supply chain problems can prevent access to a product that has been specified in the SAS-B application. It may then become necessary for a clinical re-evaluation to find a more readily available product and to apply for a new SAS-B permit for that product.

No cannabis products currently have a subsidy on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and costs can be considerable. These are typically around $5–$15 a day,16 but substantially more for patients with conditions such as epilepsy that require very high doses of CBD. It is important for prescribers to have an open conversation with their patients around likely ongoing costs. Patients receiving disability pensions, aged pensions or other Centrelink benefits may be unable to afford medicinal cannabis.

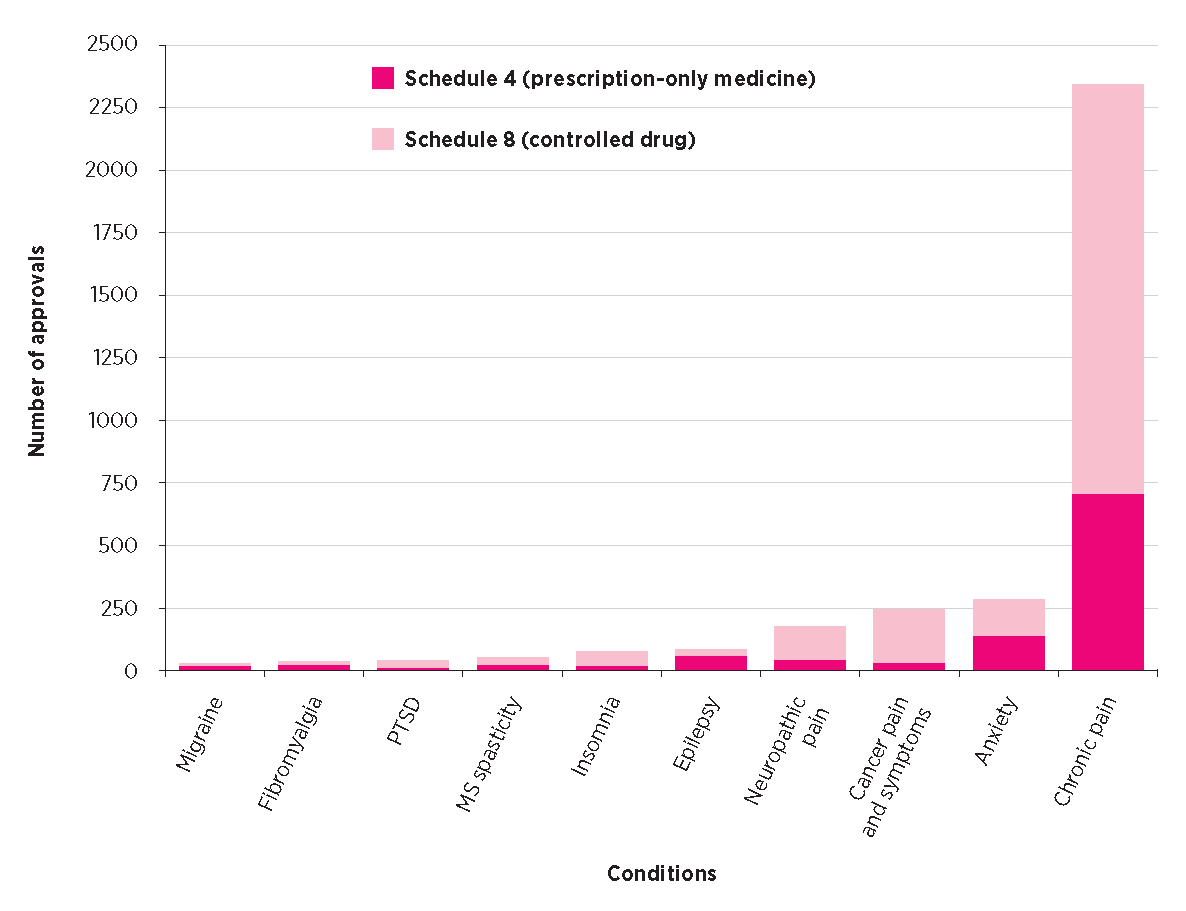

Most approvals under SAS-B are for the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain (Fig. 2). This includes conditions such as arthritis, lower back pain, neck pain and various forms of neuropathic pain. These are typically treated with oral solutions that contain THC and sometimes additional CBD. Other common conditions among SAS-B approvals include anxiety, cancer-related symptoms (e.g. pain, nausea, anorexia), epilepsy, insomnia, and spasticity in multiple sclerosis (Fig. 2). CBD-only products are being used in all of these conditions, but there is a greater use of them in patients with epilepsy and anxiety. The anxiolytic effects of CBD are described in the literature.13,17,18

PTSD post-traumatic stress disorder

MS (multiple sclerosis) spasticity includes approvals for MS spasm, pain and spasticity. Epilepsy includes approvals for epilepsy, seizure and psychogenic seizures.

Neuropathic pain includes approvals for neuropathic pain and peripheral neuropathy. Anxiety includes approvals for anxiety and social anxiety disorder.

* Data are for 3364 approvals under Special Access Scheme Category B. Sourced from Freedom of Information Request #1409 to the Therapeutic Goods Administration.

The TGA has published a series of clinical guidance documents that summarise the available evidence for medicinal cannabis products in chronic pain, palliative care, epilepsy, spasticity in multiple sclerosis and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. However, definitive evidence in support of specific medicinal cannabis products for various conditions is often not available. This absence of evidence reflects historical difficulties in undertaking clinical trials with cannabis products7 and the recency with which CBD has been identified as a therapeutic drug. Nonetheless, TGA assessments under SAS-B appear to give the benefit of the doubt with regard to evidence. SAS-B approvals have been given for conditions such as autism, insomnia and movement disorders despite a lack of compelling supportive evidence.

It is recommended that medical practitioners discuss with their patients the risks and benefits of medicinal cannabis so that the patient can provide informed consent to this therapeutic pathway. Patients need to be given information about common and serious adverse effects. Cannabis, THC and CBD are generally well tolerated by patients with few serious adverse effects.6,19-22 At higher doses, THC can have sedative effects and make naïve users feel dizzy and ‘spaced out’.6,19-22 Appetite stimulation (‘the munchies’) is also common with THC.6 A typical intoxicating dose of THC in a naïve user is at least 10 mg, although some patients may be more sensitive. Starting low and slowly titrating the dose upwards is the best practice. The more troubling symptoms of THC intoxication, such as paranoia, severe anxiety and psychotic reactions, can be minimised with careful titration and also by combining with CBD which may have antipsychotic and anxiolytic effects. Regular review of patients is recommended.

CBD has been shown to be well tolerated at very high doses (up to 5000 mg).23 CBD is a potent inhibitor of various cytochrome P450 enzymes.24,25 Higher doses may increase plasma concentrations of anticonvulsant drugs such as clobazam and topiramate.26 Children with epilepsy who are on concomitant anticonvulsant drugs may be vulnerable to related adverse effects such as sedation, gastrointestinal upset and elevated liver transaminase levels.11,27 In clinical trials outside of childhood epilepsy the only significant side effect with CBD was diarrhoea.27 Interactions of CBD with drugs such as benzodiazepines, antidepressants and opioids appear unlikely to be clinically significant in adult clinical populations, but more research is required. Given this uncertainty, upwards dose titration is a valid precautionary practice in patients given CBD-containing products, particularly if they are also taking other medicines.

Driving is a key issue to discuss with patients as it is currently illegal to drive while being treated with products containing THC. At present in Australia, if THC is detected in oral fluid by mobile drug testing, patients can be prosecuted. There is currently no exemption for people with a legitimate prescription for THC. There is however evidence suggesting that driving impairment is modest in those who repeatedly use THC.28,29 Current tests can detect cannabis for several hours after THC consumption, but there are large individual differences so some patients are more vulnerable to a positive test than others.30 Patients should wait at least six hours after consuming THC-containing products before driving and be aware that, even then, they remain vulnerable to prosecution under current laws. Issues associated with workplace use of THC-containing products also need to be carefully considered, especially for patients working in transportation industries and in workplaces requiring the safe operation of heavy machinery.

CBD is not intoxicating. There are no restrictions around driving while taking CBD-only products. THC contamination of CBD products is a significant worldwide issue and it is therefore prudent for doctors and patients to request certificates of analysis from the manufacturer.31

Cannabis is euphorigenic and can be habit- forming, leading to dependence in approximately 10% of recreational users. Sudden withdrawal can cause a clinically significant but relatively benign withdrawal syndrome that includes mild sleep and appetite disturbances, cannabis craving and emotional lability.32 The likelihood of drug-seeking behaviour in patients wishing to use medicinal cannabis products should be carefully assessed by prescribers. Patients using higher doses of THC are best gradually titrated off THC-containing products when discontinuing their use. Withdrawal from CBD does not appear to be associated with any significant discontinuation syndrome.33

Prescribing medicinal cannabis may feel like a ‘leap in the dark’ for many GPs who feel uneducated in this emerging area of clinical practice. Australian doctors are fielding daily enquiries about medicinal cannabis from their patients, so it is prudent to learn more regardless of whether they wish to prescribe cannabis or not.3 There are educational events, online courses and accredited workshops such as those by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Doctors who do not want to prescribe may wish to direct their patients to one of the many clinics specialising in cannabis access that have been established in many Australian capital cities.

Despite the exponential rise in approvals under the SAS-B scheme, surveys suggest that many Australians continue to self-medicate with illicit cannabis.34,35 Indeed, the National Drug Strategy Household Survey recently reported that 600,000 Australians use cannabis for medicinal purposes, but only 3.9% obtain it via legal pathways.36 The reasons for this may include the high cost of unregistered cannabis- based products compared to illicit cannabis (which is often home-grown), the inability to find a doctor who will assist in making an application to the TGA, lack of knowledge of official access pathways, and a reticence to discuss cannabis use with a doctor.34,35

Illicit cannabis products are likely to be suboptimal as therapeutics. They probably contain a great deal of THC and little CBD37 and may also contain contaminants such as pesticides and heavy metals. Artisanal cannabis oils used in Australia to treat intractable childhood epilepsies have pronounced variation in their cannabinoid composition. In some cases, products that were purported to be CBD-dominant were actually rich in THC.38 Products obtained through official schemes must abide by the Australian standard TGO 93 for medicinal cannabis.

While there is an intent to enable access to quality-controlled medicines via the SAS-B and Authorised Prescriber schemes, the current framework remains a work in progress. It is arguably still short of meeting community expectations around access for patients. A recent Australian Senate Inquiry14 has offered numerous recommendations for improving patient access to products, as well as identifying strategies to improve the education of doctors in this rapidly developing and sometimes challenging area of clinical practice.

Jonathon Arnold is Deputy academic director of the Lambert Initiative for Cannabinoid Therapeutics, a philanthropically funded research centre at the University of Sydney. He has served as an expert witness in various medicolegal cases involving cannabis and advised the World Health Organization in their recent expert reviews of cannabis. His research is funded by the Lambert Initiative and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Jonathon Arnold and Iain McGregor hold patents on cannabinoid therapies (PCT/AU2018/051089 and PCT/ AU2019/050554).

Iain McGregor is Academic director of the Lambert Initiative for Cannabinoid Therapeutics. He has served as an expert witness in various medicolegal cases involving cannabis, has received honoraria from Janssen, is currently a consultant to Kinoxis Therapeutics, and has received research funding and fellowship support from the Lambert Initiative, NHMRC and Australian Research Council. He holds a variety of patents for non-cannabinoid therapeutics.

Tamara Nation has received a speaker fee honorarium from Althea, Spectrum Therapeutics/Canopy Growth, Cannatrek and a case-study fee from Entoura.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by the Lambert Initiative for Cannabinoid Therapeutics. The authors gratefully acknowledge Barry and Joy Lambert for their continued support. They are grateful to Little Green Pharma for assistance in the preparation of the Table, and Rhys Cohen and Melissa Benson for assistance in the preparation of Fig. 2.

Australian Prescriber welcomes Feedback.

NPS MedicineWise. Medicinal cannabis: what you need to know. https://www.nps.org.au/professionals/medicinal-cannabis-what- you-need-to-know [cited 2020 Sep 1]

Deputy academic director, Lambert Initiative for Cannabinoid Therapeutics, Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney

Associate professor, Discipline of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine and Health,

University of Sydney

General practitioner, National Institute of Integrative Medicine, Melbourne

Academic director, Lambert Initiative for Cannabinoid Therapeutics, Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney

Professor of Psychopharmacology, School of Psychology, Faculty of Science, University of Sydney