Diagnostic tests

Testing for COVID‑19

- Anna Brischetto, Jenny Robson

- First published 15 October 2020

- Aust Prescr 2020;43:204-8

- 1 December 2020

- DOI: 10.18773/austprescr.2020.067

For a more recent article on this topic, see Testing for COVID-19: a 2023 update.

Accurate diagnostic tests that provide results in a timely manner are essential for the clinical and public health management of COVID‑19 disease.

The choice as to which test to use will depend on the clinical presentation and the stage of the illness.

Nucleic acid tests, using real‑time reverse transcriptase‑polymerase chain reaction, are the most appropriate for diagnosing acute infection. Combined deep nasal (or nasopharyngeal) and throat swabs are the preferred sample.

Serology can be used to diagnose previous infection, more than 14 days after the onset of symptoms.

Antigen tests are in development and their role is not yet defined.

Interpretation of results must take into account the pre‑test probability of the patient having the disease. This is based on their clinical presentation and epidemiological risk.

COVID‑19 is caused by the SARS‑CoV‑2 virus and was first identified after an outbreak of pneumonia in Wuhan, China in December 2019. Since then, no country has escaped the ensuing pandemic that continues on an upward trajectory. Access to accurate and reliable diagnostic testing is key to the public health response. Identifying infected individuals, tracing their contacts, and quarantine and isolation measures are an essential part of reducing the transmission, morbidity and mortality from COVID‑19.

There are a number of different diagnostic tests for COVID‑19: nucleic acid tests, serological tests for antibody detection, and antigen tests. These can be laboratory‑based and point‑of‑care tests (see Table). It is important to be aware of what the different tests are, when they should be used, what samples should be collected and how to interpret test results.

Table - Diagnostic tests for SARS‑CoV‑2 infection

|

Test |

Purpose of test |

When to order this test |

Sample type |

|

Point‑of‑care nucleic acid tests |

Diagnosis of current infection (when a rapid turnaround is required) |

Symptomatic patients early in their illness |

Combined nasopharyngeal or deep nasal with throat swab, or sputum or BAL if lower respiratory symptoms |

|

Laboratory‑based nucleic acid tests: many commercial and in‑house laboratory developed assays |

Routine diagnosis of current infection |

Symptomatic patients early in their illness |

Combined nasopharyngeal or deep nasal with throat swab, or sputum or BAL if lower respiratory symptoms |

|

Laboratory‑based testing for antibodies to various antigens including nucleocapsid and spike proteins |

Diagnosis of past infection |

At least 14 days since the onset of symptoms. Repeat testing out to 28 days is recommended when there is a high pre‑test probability |

Serum from blood sample |

|

Point‑of‑care antibody tests |

Detection of IgG and IgM antibodies |

Should not be used until at least 2 weeks post symptom onset. |

Venous or finger prick blood tests |

|

Antigen tests |

Rapid diagnosis |

Usually symptomatic patients within 5 days of symptom onset. Role for these assays not yet defined |

Respiratory specimens as for RT‑PCR. Repeat testing may be required as reduced sensitivity compared to RT‑PCR |

RT‑PCR reverse transcriptase‑polymerase chain

reaction

BAL broncho‑alveolar lavage

Ig

immunoglobulin

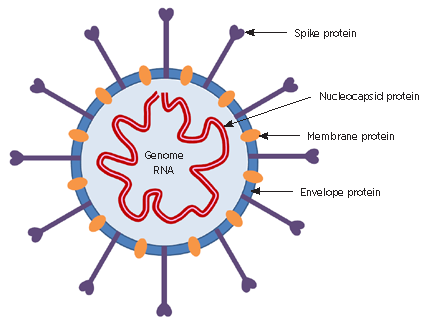

SARS‑CoV‑2 is a member of the coronavirus family. This is a diverse group of enveloped, single‑stranded, positive‑sense RNA viruses. Four important structural proteins are the most common targets for diagnostic tests (see Fig. 1):

The mean incubation period for infection with SARS‑CoV‑2 is five days, with a range of 2–14 days reported. The most common symptoms are fever, dry cough and fatigue, with sore throat, rhinorrhoea, dysgeusia and anosmia also described. Reported fatality rates vary from 0.7% to approximately 5%.2

Transmission is primarily via respiratory droplets or fomites. Viral shedding is thought to peak on or just before the onset of symptoms, with viral loads decreasing thereafter.3

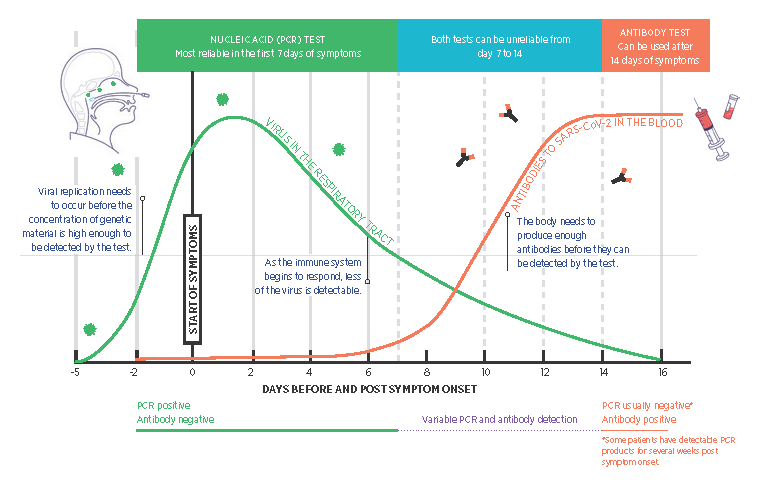

Prolonged detection of viral RNA is not uncommon, with reports of detection by PCR up to 12 weeks after symptoms have resolved.4 However, this does not necessarily mean there is infectious virus present. Transmission of the virus is thought to be unlikely 10 or more days after the onset of symptoms based on viral culture and epidemiological studies (Fig. 2).5 Asymptomatic infections are increasingly recognised as important in the ongoing transmission of the virus. However, testing should continue to be targeted and avoid non‑clinically indicated asymptomatic testing to preserve reagents and testing capacity.6

Testing should be performed on patients who have a compatible clinical illness, or as part of enhanced surveillance of asymptomatic individuals in high‑ risk settings such as returned travellers, healthcare workers, contacts of confirmed cases and in outbreak situations. Individuals in enclosed environments with an increased risk of transmission, such as aged‑care facilities, abattoirs and prisons, may also be tested. Testing guidelines should be checked as they are regularly updated.7,8

Real‑time reverse‑transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT‑PCR) assays are the cornerstone of acute diagnosis for COVID‑19 and work by detecting SARS‑CoV‑2 RNA in respiratory tract specimens.7 At least one, but often two or more RNA target sequences are generally used. While the analytical sensitivity of these tests is excellent, their clinical interpretation depends on the prevalence of SARS‑CoV‑2 in the population tested. Other factors contributing to this variability include the adequacy of the sample collected and the timing of sample collection in relation to the likelihood of viral shedding and stage of the illness (Fig. 2). A single negative result is generally sufficient to exclude disease in most cases, but in patients with a clinically compatible illness and a high index of suspicion, repeat testing should be performed. Overall, the likelihood of false positives and false negatives occurring is very low.9

To maximise the chance of virus detection, sampling the oropharyngeal (throat) and bilateral deep nasal (or nasopharyngeal) sites is recommended.10 Using the same flocked or foam swab for both is preferred. This is more sensitive than throat‑only swabs. For those with lower respiratory tract symptoms, sputum or broncho‑alveolar lavage specimens (on intubated patients) are preferred.7

Self‑collected nasal and throat swabs have been shown to be as sensitive as samples collected by healthcare workers and are an appropriate alternative.11 The option of self‑collection can be offered by a medical practitioner or under public health direction. Where possible, it should be supervised.

Saliva may be another alternative sample type, albeit slightly less sensitive. However, there is insufficient evidence at present to recommend its use.12 Although SARS‑CoV‑2 RNA has been detected in faecal samples, these specimens are not recommended for routine testing. They can be considered when there is a high suspicion of SARS‑CoV‑2 in patients with a negative PCR result on respiratory samples.

For nucleic acid testing, swabs should ideally be

placed in suitable validated liquid media and

transported at ambient temperature to the

laboratory.

A point‑of‑care RT‑PCR test, the Xpert Xpress SARS‑CoV‑2 (Cepheid, USA), is currently in use in Australia (performed on the GeneXpert system).13 The advantage of this test is the short time for a result to be available (approximately 45 minutes from the time the sample arrives), as there is no separate extraction step. However, this system is not suitable for simultaneous testing of large numbers of samples and reagent cartridges are of limited availability nationally. Similar rapid assays that include multiplexed additional respiratory virus targets are becoming available, such as QIAstat‑Dx Respiratory SARS‑CoV‑2 Panel (QIAGEN GmbH) and the cobas SARS‑CoV‑2 and Influenza A/B nucleic acid test (Roche Molecular Systems). The ID NOW COVID‑19 assay (Abbott) is in use in some point‑of‑care settings such as hospital emergency departments. It uses isothermal nucleic acid amplification technology. Analytical sensitivity is reduced compared to other sample‑to‑answer platforms.14

There are many available commercial and in‑house‑ developed nucleic acid tests in use in Australian laboratories. Extraction of the RNA from samples before amplification is required and so the total test time is approximately six hours. However, due to transport time and the need to batch samples together, the actual turnaround time is closer to 24–48 hours. The advantage of these tests is the ability to perform a large volume of tests at the same time.

New fully integrated sample‑to‑answer molecular diagnostic platforms are now available. Examples include Hologic’s Panther Fusion and Aptima SARS‑CoV‑2 assays and Roche’s cobas SARS‑CoV‑2 test, which offer high throughput, and DiaSorin Molecular’s Simplexa COVID‑19 Direct kit, which in addition offers improved turnaround times.

Serological testing detects antibody responses (IgM, IgA and IgG) to SARS‑CoV‑2 in patient sera. Due to the delay in antibody production, serology is not recommended for the diagnosis of acute infections. Sero‑positivity increases from day seven of the illness, with most patients seroconverting by day 14, although some can take up to 28 days (Fig. 2). It is thought that 5–10% of patients may never seroconvert following infection with SARS‑CoV‑2.

Assays most commonly are designed to detect antibodies to the spike protein, or the nucleocapsid protein, with the choice of antigen designed to minimise cross‑reaction against other human coronaviruses.15

Serology is recommended for:

Duration of antibody response and correlation with protection and immunity to COVID‑19 are both unknown at this time. There is early evidence to suggest that while antibodies may decline over a few months, protection from reinfection may be more durable.16

Serum should be collected from patients with a compatible clinical illness at least 14 days after the onset of symptoms. Consideration can be given to taking an earlier sample that can be stored and used for parallel testing.

COVID‑19 serology is currently performed in the laboratory using either in‑house methodology or, more commonly, commercially manufactured kits. Most laboratories are using an enzyme‑linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), either as manual ELISAs that need to be batched, or as high‑ throughput immunoassays that allow samples to be tested as they arrive. Some reference laboratories are also using neutralisation assays, microsphere immunoassays or immunofluorescent assays.7 The real‑world sensitivity of these commercial assays has been reported as 80–100% depending on the assay, with specificities of 98–100%.17 In the Australian setting where the prevalence of infection is still very low (0.1%), the predictive value of a positive test even with this high specificity is low and of the order of 10%.

To improve the positive predictive value of serological results and reduce false‑positive results, some laboratories are screening with one assay, then performing a second independent assay detecting antibodies to a different antigen on all positive results. The results of both assays will be considered when interpreting the final result.

Consultation with the laboratory regarding the interpretation of SARS‑CoV‑2 serological results is recommended. Definitive laboratory evidence of SARS‑CoV‑2 infection is seroconversion or a significant (e.g. at least fourfold) rise in either neutralising or IgG antibody concentrations. Detection of IgG in a single specimen from a person with a compatible clinical illness and with one or more defined epidemiological criteria for COVID‑19 is suggestive evidence of SARS‑CoV‑2 infection. Detection of IgM, IgA or both without IgG is not sufficient evidence of infection, and a follow‑up sample should be requested.15

A number of lateral flow point‑of‑care assays have been developed to detect SARS‑CoV‑2‑specific IgM, IgG and total antibody. Blood samples are taken from a vein or by finger prick providing a rapid turnaround time. These tests are not recommended for acute diagnosis because of the delayed antibody response. An independent evaluation of eight of these antibody tests found that they generally have not met manufacturer claims for diagnostic sensitivity.18 Whether there is a role for these tests in determining immunity for return‑to‑work purposes or population surveillance remains to be determined.

Antigen assays detect virus proteins, usually the nucleocapsid protein in respiratory samples and are used for acute diagnosis. Their availability in Australia is currently limited. While most require laboratory equipment for reading of results, some are applicable for point‑of‑care testing.

There is increasing interest in these tests because of their lower relative cost to RT‑PCR and rapid turnaround time, and can be scaled up to test large numbers of patients. However, concerns remain around their sensitivity to detect virus compared to RT‑PCR tests. Rigorous postmarket evaluation of these tests is essential. A discussion around their future role in the Australian context has recently been published.19 The widespread availability of RT‑PCR testing, generally with good turnaround times, reduces the need for antigen assays in Australia. However, there may be a role in certain particularly high‑risk settings.

Personal protective equipment consisting of gloves, surgical mask and eye protection should be used when collecting respiratory samples in symptomatic patients suspected of having SARS‑CoV‑2 infection. The need for a gown or apron should be based on a risk assessment.20 This should also be the case when collecting blood for serological testing if the patient is symptomatic, otherwise standard precautions are appropriate. The Infection Control Expert Group, together with the National COVID‑19 Evidence Task

Force, is currently analysing the high rates of infection that have been seen in some types of healthcare workers and updated recommendations are anticipated. Specimen collection has not specifically been identified as high risk.

Prompt identification of patients with SARS‑CoV‑2 infection using laboratory diagnostic tests is essential, for both the clinical monitoring and treatment of the patient and to inform subsequent quarantining and isolation. The appropriate choice of diagnostic test and sample type will maximise the chance of identifying positive cases, and minimise the unnecessary anxiety and expense of tests with little clinical use.

Conflict of interest: none declared

Australian Prescriber welcomes Feedback.

Microbiologist and Infectious diseases physician

Microbiologist and Infectious diseases physician

Sullivan Nicolaides Pathology, Bowen Hills, Brisbane