Key messages

- BP lowering is an important component in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Use absolute cardiovascular risk rather than isolated risk factors to inform treatment decisions in adults aged ≥ 45 years (≥ 35 years for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults).

- Out-of-clinic BP values are a useful adjunct to in-clinic readings.

- Start pharmacotherapy with a single active ingredient rather than a fixed-dose combination containing two or more BP lowering medicines.

- Consider coexisting conditions when choosing BP lowering therapy. Ensure active ingredients of all medicines are identified to reduce risk of adverse events from drug–drug interactions or inadvertent duplication.

- Review and encourage patient adherence to lifestyle modifications and prescribed medicines at every opportunity.

Cardiovascular risk does not only begin at 140/90 mmHg

Blood pressure is a well-established and important modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD).

In Australia, elevated BP has been the most frequently managed problem in general practice for the past decade.1 In the recent 2011–12 Australian Health Survey, one in five adults had BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg2,3 – the commonly accepted cut-off where BP shifts from being described as 'normal' to 'high', and traditionally identifies a person with hypertension.4

While it may be practical to have a BP value that is universally understood to represent a disease threshold, observational studies show that BP and cardiovascular risk have a log–linear relationship.5-7

In the Prospective Studies Collaboration meta-analysis involving a million adults aged 40–69 years with no previous CVD, the risk of CVD death doubled with each increase of 20 mmHg in systolic BP or around 10 mmHg in diastolic BP – from pressures as low as 115/75 mmHg.7 Moreover, CVD is multifactorial and studies show that the cumulative effect of these risk factors may be synergistic.8-10

Such observations have challenged the clinical relevance of using BP thresholds in isolation to determine if treatment is needed to reduce CVD risk.8,9,11

Shifting focus – assess absolute risk to guide primary prevention of CVD

'Hypertension should be managed within a comprehensive management plan to reduce BP, reduce overall cardiovascular risk and minimise end-organ damage'12 – National Heart Foundation

CVD is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Australia, affecting an estimated 22% of the adult population (3.7 million people)13 and accounting for 31% of all deaths.14 CVD is also a major contributor to our national burden of disease (18% overall), second only to cancer.15 Many of the factors underlying and driving this CVD burden are largely modifiable and include high BP, high cholesterol, lack of exercise, high body mass index and smoking (Figure 1).

To account for the large number of possible risk factors and the potential interplay between them, local and international guidelines for primary CVD prevention have been moving away from managing isolated risk factors, instead basing management on absolute CVD risk.11,16-19

Such an approach is advocated20 because it:

- reduces the chance of undertreating patients with multiple – but only slightly abnormal – risk factors, who are actually at high overall risk of CVD8,11,21

- minimises over-treatment of patients with only a single raised risk factor but who are at low overall risk of CVD8,11,21

- maximises the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatment by targeting individuals most likely to benefit from intervention.11,21

Several tools, including web-based risk calculators and charts are available for Australian health professionals to assess an individual's absolute CVD risk and provide a more complete picture of cardiovascular health.

These tools are based on the Framingham risk equation that combines major risk factors such as age, sex, smoking, BP and cholesterol levels to calculate the likelihood (as a percentage) of a person experiencing a cardiovascular event (ie, stroke, transient ischaemic attack, myocardial infarction, angina) within the next 5 years.20 This likelihood (absolute risk) is categorised as being low (< 10%), moderate (10%–15%) or high (> 15%).20

When and who to assess – it's not one size fits all

All adults from 18 years of age should have their BP measured at least every 2 years.28

Consider absolute risk calculations for adults aged 45–74 years (or 35–74 years for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults) who are not known to have CVD.20

Some individuals will not need a formal absolute CVD risk calculation (regardless of their age) because they are already at high risk of a cardiovascular event.20 This group includes those with:

- history of cardiovascular events or known CVD

- diabetes and age > 60 years

- diabetes with microalbuminuria (> 20 micrograms/min or urinary albumin:creatinine ratio > 2.5 mg/mmol for males, > 3.5 mg/mmol for females)

- moderate or severe chronic kidney disease

- previous diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia

- systolic BP ≥ 180 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 110 mmHg

- serum total cholesterol > 7.5 mmol/L

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults aged over 74 years.11,16,20

In people younger than 45 years, or 35 years for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, who present with high BP but do not fit any criteria listed above, investigate for undiagnosed causes of secondary hypertension such as sleep apnoea.20

Room to improve

Current research suggests the uptake and implementation of absolute risk guidelines are not consistent among Australian GPs.22-26

Use of CVD risk calculators was reported by only 60% of GPs participating in the AusHEART study,23 while a recent analysis from the BEACH program noted that 47% of patients with high BP had not undergone absolute risk assessment in the past.27

Discordance between GP estimates of risk and actual calculated risk has also been recorded, leading to treatment decisions that are often inconsistent with guidelines.23,24,26 For example, in AusHEART 45% of patients (with or without CVD) not prescribed BP-lowering medicines were indicated for treatment when Australian guidelines were applied.

Similarly, 40% of patients receiving medicines were assessed as low absolute risk according to the same guidelines and may have been effectively managed with lifestyle modification.23 In some cases this discordance may be because a GP has determined risk based on individual risk factors in preference to absolute risk.24

Discuss absolute risk with patients

Encouraging changes in lifestyle or adherence to medicines can be problematic in at-risk patients who are asymptomatic. Using a visual aid such as the Australian cardiovascular risk charts or an interactive tool such as the online calculator may help some people better understand the cumulative effect of their risk factors and how these may be attenuated.

Open the online cardiovascular risk calculator

Recent Australian research has reported that GPs use a number of strategies to communicate absolute risk, depending on their perception of patient risk, motivation and anxiety. For example, a 'positive' strategy that provided reassurance and motivation was employed for people perceived to be at lower CVD risk, while for patients at higher risk GPs described using the absolute risk tools as a 'scare tactic' strategy to motivate action.22,31

Inform treatment using absolute risk and thorough clinical assessment

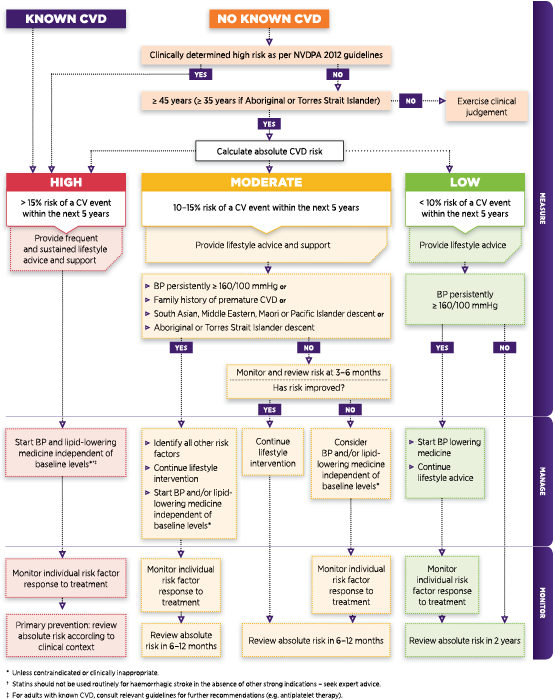

Figure 2: Cardiovascular risk assessment and management algorithm20

Adapted with permission from NVDPA

When assessing absolute risk, it is also important to check for associated clinical conditions (eg, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, CHD) and/or end-organ damage (eg, left ventricular hypertrophy, microalbuminuria, chronic kidney disease, vascular disease).12 This information is essential to assist with the development of a comprehensive management plan that may include recommendations for lifestyle and behavioural changes as well as pharmacological interventions to reduce CVD risk.12,20

Current guidelines provide general recommendations around treatment options according to absolute risk levels and other clinical characteristics that may be present (Figure 2).

Measuring blood pressure

'Blood pressure must be measured accurately to ensure patients in need of treatment are correctly identified.'32

In-clinic BP measurements are the frontline of BP assessment and monitoring in primary care. When taken with a calibrated sphygmomanometer these values can be very accurate if measured using best practice.12

However, in-clinic measurements can be confounded by limitations such as the reliability of the devices or techniques used to obtain a reading, the potential for a 'white coat' or 'masked' effect, or the small number of readings able to be taken in a single visit.33

In addition, given that BP naturally fluctuates throughout the day and can be affected by different activities and substances,12 in-clinic measurement can at best provide only a snapshot.

To achieve a good assessment of BP take multiple measurements on separate occasions.12 At the initial BP assessment, take measurements from both arms. If there is a variation of > 5 mmHg between arms, use the arm with the higher reading for all subsequent measurements.12

For manual devices the recommendation is that at least two measurements are taken one or more weeks apart (unless BP elevation is severe, in which case a clinician may take the follow-up measurement earlier).12 If an automated device is used, take at least three measurements, and average the second and third measurements.36,37

Multiple factors can affect the accuracy of an in-clinic BP reading and cause a discrepancy between actual and measured BP (Table 1).38

Table 1. Factors that can increase in-clinic SBP measurements38

Technique-related factors | Patient-related factors |

|---|---|

|

|

When to consider out-of-clinic measures

Assessment of BP outside the clinic, using either 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) or home BP monitoring (HBPM), can complement in-clinic BP measurements and better characterise BP profiles in some patients.12,20,33,37,39-41 Evidence also suggests that out-of-clinic BP measurements may be more useful for predicting future CV risk than those recorded in-clinic.33,39

Use out-of-clinic BP monitoring to confirm the presence of persistently elevated BP before calculating absolute CVD risk; convert the reading to an in-clinic equivalent before use.39,40 At present, only ambulatory BP readings have published in-clinic equivalents (Table 2).39

However, it is widely recognised in the literature that home BP values:

- are similar to daytime ambulatory BP values42-45 – with both sharing the same threshold of 135/85 mmHg for 'high' BP12,41

- are generally lower than in-clinic values18 although the difference between the two decreases as BP approaches 'normal values'.43,44

Table 2. Ambulatory BP and in-clinic BP systolic BP equivalentsa (can be used to calculate absolute cardiovascular risk)12,39

| Women | Men | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Age (years) | Age (years) | |||||||

Clinic SBP | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 |

179 | 160 | 165 | 166 | 164 | 175 | 170 | 170 | 167 |

160 | 154 | 151 | 150 | 149 | 158 | 155 | 154 | 152 |

140 | 137 | 135 | 134 | 133 | 140 | 139 | 137 | 136 |

120 | 120 | 119 | 118 | 118 | 123 | 122 | 121 | 120 |

aAmbulatory BP predicted from daytime seated in-clinic BP (n = 5327)46 grouped by age and sex.

ABPM and HBPM can also be used to confirm the presence of white-coat (elevated in-clinic but normal out-of-clinic BP) and masked hypertension (normal in-clinic but elevated out-of-clinic BP),12,33,39 while ABPM is also indicated when nocturnal hypertension, or nocturnal non-dipping (no night-time lowering of BP) are suspected.12,39

Once identified, these patients benefit from continued monitoring,33,39 as both white-coat and masked hypertension have been associated with the development of high BP and the development of impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes,47 while nocturnal non-dipping has been associated with increased risk of stroke, end-organ damage and cardiovascular events, including death.48,49

Recommend lifestyle modification regardless of risk level

Positive changes to lifestyle may help to avoid, delay or reduce the need for BP-lowering medicines.12,20,50

Studies have demonstrated that, regardless of a patient's absolute risk, lifestyle modifications are an important and effective component of any CVD risk-reducing strategy.50 Substantial improvements to BP and cardiovascular risk can be achieved with lifestyle modifications such as changes to eating patterns, moderating alcohol intake, weight loss, stopping smoking and regular physical activity.50,51

Further information for encouraging and maintaining lifestyle changes can be found in the RACGP SNAP guide.

Start treatment using a single active ingredient

When lifestyle interventions alone cannot reduce absolute risk sufficiently, guidelines recommend starting treatment with one of the following main classes of BP-lowering medicines:12,20,37

- angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE inhibitor)

- angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARB)

- calcium-channel blockers (CCB)

- low-dose thiazide diuretics.

As several large systematic reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated that at standard doses all these classes lower BP to a similar extent,52-56 base choice of initial and subsequent treatments, if needed, on:12,20,37

- patient age

- presence of clinical comorbidities or end-organ damage

- presence of other coexisting conditions that either favour or limit the use of particular classes

- potential interactions with other medicines

- implications for adherence

- cost.

Beta blockers are no longer a recommended first-line medicine for primary prevention of CVD, as evidence suggests they are less effective for preventing stroke.52,55,56

Use a stepwise approach to lower BP

In adults with uncomplicated high BP who are unable to achieve BP control with monotherapy, first consider possible barriers to adherence. However, it is generally accepted that most patients will require a combination of two or more BP-lowering agents to achieve adequate BP lowering.12,57

If a satisfactory reduction in BP is not achieved after an appropriate trial of monotherapy, consider a stepwise approach in which medicines from different classes are gradually introduced.12 There are also some specific combinations that have proven more effective than others based on a range of patient factors (Table 3).12

Table 3. Recommendations for combining BP-lowering medicines12,37

| Effective combinations | Combinations to avoid | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ACE inhibitor or ARB + CCB | Especially in the presence of diabetes or lipid abnormalities | ACE inhibitor or ARB + potassium-sparing diuretic | Risk of hyperkalaemia |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB + thiazide diuretic | Especially in the presence of heart failure or post stroke | Beta blocker + verapamil or diltiazem | Risk of heart block |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB + beta blocker | Recommended post-MI or heart failure | ACE inhibitor + ARB | Increased risk of hypotensive symptoms, syncope and renal dysfunction. Only use with specialist advice |

| Beta blocker + dihydropyridine CCB | Especially in the presence of heart disease | Thiazide diuretic + beta blocker | Not recommended in people with glucose intolerance, metabolic syndrome or established diabetes |

Fixed-dose combinations – evidence still unclear

Current guidelines acknowledge that fixed-dose combination (FDC) medicines can offer convenience to patients and may simplify therapy.12,19,20,37 However, data supporting their use in treatment-naïve patients are limited58 and there is lack of consensus on when they can be introduced in a treatment strategy.12,19 ,20,37,59

In Australia, PBS-listed FDC medicines are listed as restricted benefits and are not subsidised if used to start BP-lowering treatment. The National Heart Foundation recommends an FDC only after dual or triple combination therapy (as separate products) has been established.12 Other local guidelines discuss FDCs as an option when initial management with monotherapy has been ineffective.37

Introducing an FDC after BP has been stabilised on the individual components may also reduce potential risk of adverse events among people in whom a large drop in BP might be poorly tolerated (ie, elderly patients).59

Encourage adherence to medication and lifestyle modification

A key to success in preventing and managing cardiovascular disease is adherence to, and persistence with, prescribed medicines and lifestyle recommendations.61

Non-adherence to BP lowering medicines and lifestyle changes can have a direct impact on patient outcomes (ie, increased rates of cardiovascular events or death).61-63

However, given the largely asymptomatic nature of high BP, patients may not understand or accept the health risks associated with their diagnosis and be less motivated to take medicines or follow lifestyle recommendations.61,62

This can make encouraging adherence for a long-term condition such as high BP challenging.64

Multiple reasons underlying patient non-adherence have been identified. These can be intentional (eg, an active patient decision, based on balancing perceived benefits of treatment against the perceived risks) or unintentional (eg, patient doesn't know how/is unable to take their medicine(s), forgetfulness). Adherence can also be influenced by:5,62,65 ,66

- factors such as ethnicity, education, beliefs, motivation and attitude

- the patient–prescriber relationship

- health literacy

- therapy-related factors (eg, treatment complexity, treatment duration, medication side effects)

- economic factors (eg, cost and income, social support).

Assess and optimise adherence at every opportunity

View each meeting with a patient as an opportunity to encourage and assess adherence to lifestyle modification and medication.

There is currently no gold standard for measuring medicine adherence in patients, although there are strategies available to use in everyday practice such as: 61

- pill counts

- pharmacy refill records

- prescription records in electronic medical notes

- patient self-reporting (eg, diary).

Asking specific and structured questions may identify patients who require help to improve adherence. For example, an Australian study using a validated four-item patient questionnaire – the Morisky instrument – reported that patients who answered yes to the question 'Did you ever forget to take your medication?' were significantly more likely to experience a first cardiovascular event or a fatal other cardiovascular event compared with patients who answered no.63

Deliver information in a tailored and timely way

Several interventions have been shown to modestly improve adherence to medicines in people with high BP.68,69 However, no single strategy has consistently demonstrated effectiveness and no strategy has utility for all patient groups.61,62,66,69

People differ in the type and amount of information they need and want.66 Use clinical judgment and an understanding of the patient's social, cultural and medical background to guide when and how much information is required and which interventions may be most appropriate to support adherence for an individual patient.

Successful strategies that have been reported to improve adherence include:41,68,69

- simplification of treatment and of medication packaging (eg, WebsterPaks)

- home BP monitoring by patients

- patient-centred motivational counselling

- daily reminder charts

- social and family support

- telephone calls from nurses (and pharmacists?)

- telephone-linked computer counselling.

The MedicineWise smartphone app allows patients to set alarms for medicine doses and set calendar reminders for refilling prescriptions.

For further information on assessing and addressing adherence to medicines

Expert reviewer

Prof Nicholas Zwar, School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney

References

- Britt H, Miller GC, Henderson J, et al. A decade of Australian general practice activity 2004\u201305 to 2013\u201314. General practice series no 37.Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2014. [Online] (accessed 16 December).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4364.0.55.002 - Australian Health Survey: Health Service Usage and Health Related Actions, 2011\u201312. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013. [Online] (accessed 16 December).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4364.0.55.001 - Australian Health Survey: First Results, 2011\u201312. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2012. [Online] (accessed 16 December).

- World Health Organization. A global brief on hypertension: silent killer, global public health crisis. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2013. [Online] (accessed 16 December 2014).

- Lawes CM, Rodgers A, Bennett DA, et al. Blood pressure and cardiovascular disease in the Asia Pacific region. J Hypertens 2003;21:707\u201316. [PubMed].

- MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet 1990;335:765\u201374. [PubMed].

- Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, et al. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002;360:1903\u201313. [PubMed].

- Jackson R, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, et al. Treatment with drugs to lower blood pressure and blood cholesterol based on an individual's absolute cardiovascular risk. Lancet 2005;365:434\u201341. [PubMed].

- Anderson KM, Odell PM, Wilson PW, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. Am Heart J 1991;121:293\u20138. [PubMed].

- Neaton JD, Blackburn H, Jacobs D, et al. Serum cholesterol level and mortality findings for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. Arch Intern Med 1992;152:1490\u2013500. [PubMed].

- Nelson MR and Doust JA. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: new guidelines, technologies and therapies. Med J Aust 2013;198:606\u201310. [PubMed].

- National Heart Foundation of Australia (National Blood Pressure and Vascular Disease Advisory Committee). Guide to management of hypertension 2008. Updated December 2010. Canberra: National Heart Foundation of Australia, 2010. [Online] (accessed 16 December).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease\u2014 Australian facts: Prevalence and incidence. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2014. [Online] (accessed 16 December 2014).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease\u2014 Australian facts: Mortality. Canberra: AIHW, 2014. [Online] (accessed 16 December 2014).

- Begg S, Vos T, Barker B, et al. The burden of disease and injury in Australia 2003. Australia, 2007. [Online] (accessed 16 December 2014).

- Nelson MR. Management of High Blood Pressure in Those without Overt Cardiovascular Disease Utilising Absolute Risk Scores. Int J Hypertens 2011;2011:595791. [PubMed].

- Canadian Hypertension Education Program. 2012 CHEP Recommendations for Management of Hypertension. Markham: Hypertension Canada, 2012. [Online] (accessed 16 December 2014).

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2013;34:2159\u2013219. [PubMed].

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2014;311:507\u201320. [PubMed].

- National Vascular Disease Prevention Alliance. Guidelines for the management of absolute cardiovascular disease risk. 2012. [Online] (accessed 16 December).

- Doust J, Sanders S, Shaw J, et al. Prioritising CVD prevention therapy: Absolute risk versus individual risk factors. Aust Fam Physician 2012;41:805\u20139. [PubMed].

- Bonner C, Jansen J, McKinn S, et al. General practitioners' use of different cardiovascular risk assessment strategies: a qualitative study. Med J Aust 2013;199:485\u20139. [PubMed].

- Heeley EL, Peiris DP, Patel AA, et al. Cardiovascular risk perception and evidence--practice gaps in Australian general practice (the AusHEART study). Med J Aust 2010;192:254\u20139. [PubMed].

- Jansen J, Bonner C, McKinn S, et al. General practitioners' use of absolute risk versus individual risk factors in cardiovascular disease prevention: an experimental study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004812. [PubMed].

- Webster RJ, Heeley EL, Peiris DP, et al. Gaps in cardiovascular disease risk management in Australian general practice. Med J Aust 2009;191:324\u20139. [PubMed].

- Stocks N, Allan J, Frank O, et al. Improving attendance for cardiovascular risk assessment in Australian general practice: an RCT of a monetary incentive for patients. BMC Fam Pract 2012;13:54. [PubMed].

- Family Medicine Research Centre. SAND abstract number 210 from the BEACH program 2012\u201313: Management of hypertension in general practice patients. Sydney: Family Medicine Research Centre, 2013. [Online] (accessed 16 December 2014).

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice. East Melbourne: Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2012. [Online] (accessed 16 December 2014).

- Zomer E, Owen A, Magliano DJ, et al. Validation of two Framingham cardiovascular risk prediction algorithms in an Australian population: the 'old' versus the 'new' Framingham equation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2011;18:115\u201320. [PubMed].

- Wang Z and Hoy WE. Is the Framingham coronary heart disease absolute risk function applicable to Aboriginal people? Med J Aust 2005;182:66\u20139. [PubMed].

- Bonner C, Jansen J, McKinn S, et al. Communicating cardiovascular disease risk: an interview study of General Practitioners' use of absolute risk within tailored communication strategies. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:106. [PubMed].

- Martin SA, Boucher M, Wright JM, et al. Mild hypertension in people at low risk. BMJ 2014;349:g5432. [PubMed].

- Pickering TG, White WB, Giles TD, et al. When and how to use self (home) and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Am Soc Hypertens 2010;4:56\u201361. [PubMed].

- Howes F, Hansen E, Williams D, et al. Barriers to diagnosing and managing hypertension - a qualitative study in Australian general practice. Aust Fam Physician 2010;39:511\u20136. [PubMed].

- Howes F, Hansen E and Nelson M. Management of hypertension in general practice - a qualitative needs assessment of Australian GPs. Aust Fam Physician 2012;41:317\u201323. [PubMed].

- Myers MG, Godwin M, Dawes M, et al. Measurement of blood pressure in the office: recognizing the problem and proposing the solution. Hypertension 2010;55:195\u2013200. [PubMed].

- Therapeutic Guidelines Limited. Cardiovascular [revised November 2014]. eTG complete [Internet]. Melbourne: 2014; etg43. [Online] (accessed 16 December 2014).

- Handler J. The Importance of Accurate Blood Pressure Measurement. Perm J 2009;13:51\u20134. [PubMed].

- Head GA, McGrath BP, Mihailidou AS, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in Australia: 2011 consensus position statement. J Hypertens 2012;30:253\u201366. [PubMed].

- Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, et al. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for home blood pressure monitoring. J Hum Hypertens 2010;24:779\u201385. [PubMed].

- McGrath BP. Home monitoring of blood pressure. Aust Prescrib 2015;38:16\u20139. [Online] (accessed 16 December 2014).

- Sega R, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, et al. Prognostic value of ambulatory and home blood pressures compared with office blood pressure in the general population: follow-up results from the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate e Loro Associazioni (PAMELA) study. Circulation 2005;111:1777\u201383. [PubMed].

- Schettini C, Bianchi M, Nieto F, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure: normality and comparison with other measurements. Hypertension Working Group. Hypertension 1999;34:818\u201325. [PubMed].

- Mancia G, Sega R, Bravi C, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure normality: results from the PAMElA study. J Hypertens 1995;13:1377\u201390. [PubMed].

- Little P, Barnett J, Barnsley L, et al. Comparison of agreement between different measures of blood pressure in primary care and daytime ambulatory blood pressure. BMJ 2002;325:254.

- Head GA, Mihailidou AS, Duggan KA, et al. Definition of ambulatory blood pressure targets for diagnosis and treatment of hypertension in relation to clinic blood pressure: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2010;340:c1104. [PubMed].

- Mancia G, Bombelli M, Facchetti R, et al. Increased long-term risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus in white-coat and masked hypertension. J Hypertens 2009;27:1672\u201378. [PubMed].

- Ohkubo T, Hozawa A, Yamaguchi J, et al. Prognostic significance of the nocturnal decline in blood pressure in individuals with and without high 24-h blood pressure: the Ohasama study. J Hypertens 2002;20:2183\u20139.

- Ohkubo T, Imai Y, Tsuji I, et al. Relation between nocturnal decline in blood pressure and mortality. The Ohasama Study. Am J Hypertens 1997;10:1201\u20137.

- Huang N. Lifestyle management of hypertension. Aust Prescr 2008;31:150\u20133. [Online].

- Khan NA, Hemmelgarn B, Herman RJ, et al. The 2009 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 2--therapy. Can J Cardiol 2009;25:287\u201398. [PubMed].

- Law MR, Morris JK and Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ 2009;338:b1665. [PubMed].

- Turnbull F, Neal B, Ninomiya T, et al. Effects of different regimens to lower blood pressure on major cardiovascular events in older and younger adults: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2008;336:1121\u20133. [PubMed].

- Wang JG, Staessen JA, Franklin SS, et al. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure lowering as determinants of cardiovascular outcome. Hypertension 2005;45:907\u201313. [PubMed].

- Lindholm LH, Carlberg B, Samuelsson O. Should beta blockers remain first choice in the treatment of primary hypertension? A meta-analysis. Lancet 2005;366:1545\u201353. [PubMed].

- Messerli FH, Bangalore S and Julius S. Risk/benefit assessment of beta-blockers and diuretics precludes their use for first-line therapy in hypertension. Circulation 2008;117:2706\u201315; discussion 15. [PubMed].

- Nelson M. Drug treatment of elevated blood pressure. Australian Prescriber 2010;33:108\u201312. [Online] (accessed 16 December 2014).

- Gupta AK, Arshad S and Poulter NR. Compliance, safety, and effectiveness of fixed-dose combinations of antihypertensive agents: a meta-analysis. Hypertension 2010;55:399\u2013407. [PubMed].

- Canadian Hypertension Education Program. 2014 CHEP Recommendations for Management of Hypertension. Markham: Hypertension Canada, 2014.

- Gadzhanova S, Ilomaki J and Roughead EE. Antihypertensive use before and after initiation of fixed-dose combination products in Australia: a retrospective study. Int J Clin Pharm 2013;35:613\u201320. [PubMed].

- Aslani P, Krass I, Bajorek B, et al. Improving adherence in cardiovascular care. A toolkit for health professionals. National Heart Foundation of Australia, 2011. [Online] (accessed 16 December 2014).

- World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. World Health Organization, 2003. [Online] (accessed 16 December 2014).

- Nelson MR, Reid CM, Ryan P, et al. Self-reported adherence with medication and cardiovascular disease outcomes in the Second Australian National Blood Pressure Study (ANBP2). Med J Aust 2006;185:487\u20139. [PubMed].

- Simons LA, Ortiz M and Calcino G. Persistence with antihypertensive medication: Australia-wide experience, 2004\u20132006. Med J Aust 2008;188:224\u20137. [PubMed].

- Jin J, Sklar GE, Min Sen Oh V, et al. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient's perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2008;4:269\u201386. [PubMed].

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Medicines adherence: Involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. NICE clinical guideline 76. 2009. [Online] (accessed 16 December 2014).

- Morisky DE, Green LW and Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care 1986;24:67\u201374. [PubMed].

- Schroeder K, Fahey T and Ebrahim S. Interventions for improving adherence to treatment in patients with high blood pressure in ambulatory settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004:CD004804. [PubMed].

- Glynn LG, Murphy AW, Smith SM, et al. Interventions used to improve control of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010:CD005182. [PubMed].