Acute knee pain presentations in middle-aged patients: what is the role of MRI?

Knee pain is a common symptom among middle-aged or older people and one that often prompts them to visit their GPs. Learn about the role of MRI in diagnosis.

Key points

- Always take a thorough history, examine the affected knee(s) and consider whether or not any further investigations are needed to make a diagnosis.

- Apply Ottawa rules to determine if diagnostic X-rays are necessary for suspected fractures – preferably including weight-bearing image requests in your referral – and review them before devising a care plan.

- Remember that every care plan must be based on a diagnosis (eg, fracture) and that most uncomplicated acute knee pain will resolve with simple conservative measures.

- Review the patient on several occasions, if needed, to assess progress.

- Avoid unnecessary further investigation.

- Be mindful that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) does not provide additional useful information in most cases of knee injury, especially when degenerative joint disease is evident on plain X-ray (eg, it often reveals incidental findings that are unrelated to the patient’s pain).

- Recognise that surgical procedures (eg, arthroscopy) have a very limited role in the treatment of acute knee pain at any age, but especially when patients are middle-aged or older.

History and a physical exam are usually sufficient

Diagnosing acute knee pain 2,9,20

History

- Ask about the mechanism and early features of injury.

- Ask about any previous injuries.

Physical examination

- Conduct relevant physical tests (eg, assess range of motion, check for presence of an effusion, perform ligament laxity tests and tests for meniscal tear).

Further investigations (if findings are likely to change management)

- Apply Ottawa Knee Rules to determine whether radiography is warranted for suspected fractures.

Meniscal damage is not always clinically relevant

Degenerative meniscal injury is common among middle-aged and older people. It often accompanies knee OA and/or coexists with degenerative changes in other knee joint structures.12-15

However:

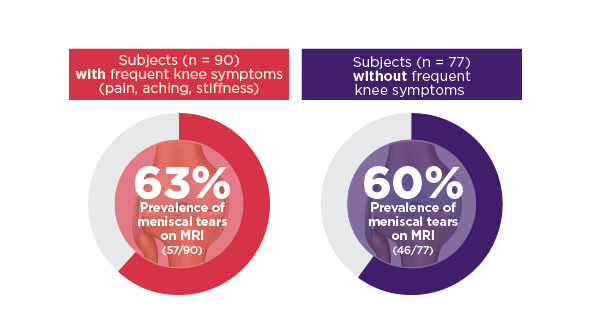

- meniscal abnormalities (eg, tears) may not be the underlying cause of acute knee pain5,12,14-17 and most authors have reported a negligible correlation between MRI-detected meniscal tears and pain (Figure 1).14,16,17,21

- specific interventions to treat a suspected meniscal tear are unlikely to be warranted if a patient's pain or other symptoms are due to damage elsewhere in the knee.14-16

Suspected or apparent meniscal abnormalities may be completely unrelated to a patient's acute knee pain, especially if he/she has coexistent OA.

Prevalence of meniscal tears among middle-aged and elderly people with radiographic osteoarthritis

Data based on 167 ambulatory subjects aged 50–90 years with radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis; selection was not made on the basis of knee or other joint problems. Integrity of the menisci in the right knee was assessed using MRI. Radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis was considered present if the Kellgren–Lawrence grade was 2 or higher.14

The role of diagnostic imaging

Diagnostic knee MRI – when is it needed?

- after an appropriate period of conservative management (approx. 6–8 weeks), when there is doubt about the diagnosis following history/examination.a,9,22

- when the level of patient disability after 6–8 weeks is such that surgery is being considered as part of a shared decision-making approach.9

- when the presence of other complex or unusual pathology is suspected (eg, a tumour in or around the joint).22

- when comprehensive history and examination does not suggest cruciate or collateral ligament or meniscal injury.9,22

- when surgical intervention is not being considered.9

- when degenerative joint disease is evident on plain X-rays (NOTE: MRI does not provide additional useful information in this situation).22

a For example: In cases of true 'knee locking', where there is a 'mechanical block' that prevents a full range of movement; or when there appears to be mechanical instability, causing the knee to buckle or give way.24

Is MRI scanning being overused?

- 90% of 100 knee MRIs ordered by a group of 32 GPs (for 100 consecutive patients aged ≥ 40 years) had resulted in either no change in their treatment plan or a referral to a specialist.5

- 88 of these 100 knee MRIs had been unnecessary, in the opinion of orthopaedic specialists, because, in these cases, it had been possible to make the diagnosis via history, physical examination and/or X-rays alone.5

Before ordering MRI

- Ask: Is the result likely to change the treatment plan?9

- Manage patient expectations 3,8,26

- Discuss the expected value of the investigation you are about to order with the patient (the extent to which it is likely to help you make a correct diagnosis, or alter the recommended treatment strategy).

- Clearly explain why you have chosen to order (or not to order) an MRI scan.

- Consider referral to or consultation with relevant specialist when appropriate.7

Incidental MRI findings can be a potential distraction

- MRI frequently reveals apparent meniscal signal changes that are reported as abnormalities or tears, as incidental findings, often in asymptomatic knees and also when there is no radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis (OA).11,12,14-17,21,27

- In one study, use of MRI revealed lesions in the knee joints of approximately 90% of middle-aged and elderly people whose knee radiographs did not demonstrate any features of OA, regardless of whether they reported pain.9,11

- MRI may even suggest the presence of a meniscal tear when there is no tear at all.8,28

Managing acute knee pain

- Not all meniscal and ACL tears require surgery (low-grade injuries respond well to conservative therapies).9

- At least one group of study investigators has recommended that clinicians adopt a 'wait-and-see' approach when managing traumatic knee disorders, after finding that the vast majority of patients report clinically relevant recovery, regardless of whether MRI reveals a meniscal tear, ligament lesion or no identifiable damage at all.35

When seeking to treat symptoms of degenerative joint disease in middle-aged patients, GPs are advised always to initiate conservative, non-surgical interventions as first-line therapy (eg, weight loss interventions, appropriate exercise regimens, physiotherapy, use of simple analgesics,b,3,8,30 In each case, the effectiveness of prescribed or recommended interventions should be periodically reviewed, over several weeks, or even months, to determine whether the patient's treatment plan needs to be adjusted.

b Unless arthroscopy/surgical interventions definitely indicated, for example, evidence of loose bodies or mechanical symptoms, such as locking, giving way or catching, or some other serious underlying disorder.

Advice for patients and clinicians

The 4 Ms for patients 3,37

- Modify lifestyle (eg, reduce weight, increase or change exercise).

- Minimise loads on the knee.

- Maintain strength of muscles that move and support the knee joint (by performing simple, appropriate exercises).

- Medicate with simple over-the-counter analgesics (eg, paracetamol).

Advice for clinicians

- Manage the patient's expectations – explain the likely cause(s) of pain, the rationale for performing specific investigations (eg, MRI) and the aims of specific treatments or interventions.

- Favour simple conservative interventions whenever possible, ensuring that sufficient time is allowed for them to work.

- Recognise that surgical procedures (eg, arthroscopy) have a limited role in the management of acute knee pain in middle-aged or older patients and may cause irreversible side effects. Only recommend when definitely indicated.

- Periodically review the effectiveness of interventions and reconsider management strategy, or refer, if symptoms persist.

Expert reviewer

Dr John North

Senior Visiting Orthopaedic Surgeon

Princess Alexandra and Mt Isa Hospitals, Queensland

Past president, Australian Orthopaedic Association

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. What is osteoarthritis? Canberra, ACT, Australia: AIHW, 2020 (accessed 3 September 2020)).

- Calmbach WL, Hutchens M. Evaluation of patients presenting with knee pain: Part II. Differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:917-22.

- Grainger R, Cicuttini FM. Medical management of osteoarthritis of the knee and hip joints. Med J Aust 2004;180:232-6.

- Lyu S-R, Lee C-C, Hsu C-C. Medial abrasion syndrome: A neglected cause of knee pain in middle and old age. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e736.

- Petron DJ, Greis PE, Aoki SK, et al. Use of knee magnetic resonance imaging by primary care physicians in patients aged 40 years and older. Sports Health 2010;2:385-90.

- Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ 2003;81:646-56.

- Australian Knee Society, Australasian Musculoskeletal Imaging Group. Joint AKS-AMSIG submission to the Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Healthcare on the radiological investigation of knee osteoarthritis (accessed 15 July 2016).

- Pompan DC. Reassessing the role of MRI in the evaluation of knee pain. Am Fam Physician 2012;85:221-4.

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Clinical guidance for MRI referral. East Melbourne: RACGP, 2013 (accessed 10 July 2015).

- Wenham CY, Grainger AJ, Conaghan PG. The role of imaging modalities in the diagnosis, differential diagnosis and clinical assessment of peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:1692-702.

- Guermazi A, Hayashi D, Roemer FW, et al. Prevalence of abnormalities in knees detected by MRI in adults without knee osteoarthritis: population based observational study (Framingham Osteoarthritis Study). BMJ 2012;345:e5339.

- Thorlund JB, Juhl CB, Roos EM, et al. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee: systematic review and meta-analysis of benefits and harms. BMJ 2015;350:h2747.

- Braun HJ, Gold GE. Diagnosis of osteoarthritis: imaging. Bone 2012;51:278-88.

- Englund M, Guermazi A, Gale D, et al. Incidental meniscal findings on knee MRI in middle-aged and elderly persons. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1108-15.

- Mezhov V, Teichtahl A, Strasser R, et al. Meniscal pathology - the evidence for treatment. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:206.

- Troupis JM, Batt MJ, Pasricha SS, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in knee synovitis: clinical utility in differentiating asymptomatic and symptomatic meniscal tears. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2015;59:1-6.

- Bhattacharyya T, Gale D, Dewire P, et al. The clinical importance of meniscal tears demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85-A:4-9.

- Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, et al. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1675-84.

- Sowers M, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Jacobson JA, et al. Associations of anatomical measures from MRI with radiographically defined knee osteoarthritis score, pain, and physical functioning. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93:241-51.

- Calmbach WL, Hutchens M. Evaluation of patients presenting with knee pain: Part I. History, physical examination, radiographs, and laboratory tests. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:907-12.

- Deshpande BR, Losina E, Smith SR, et al. Association of MRI findings and expert diagnosis of symptomatic meniscal tear among middle-aged and older adults with knee pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord 2016;17:154.

- Skinner S. MRI of the knee. Aust Fam Physician 2012;41:867-9.

- Government of Western Australia. Diagnostic Imaging Pathways - Knee Pain (Post Traumatic). Western Australia: Government of Western Australia, 2013 (accessed 20 July 2015).

- Shiraev T, Anderson S, Hope N. Meniscal tear presentation, diagnosis and management. Aust Fam Physician 2012;41:182-7.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Khanuja H. Abstract 299. Annual Meeting. San Diego, California, USA.: 2011 (accessed 15 July 2016).

- Song YD, Jain NP, Kim SJ, et al. Is knee magnetic resonance imaging overutilized in current practice? Knee Surg Relat Res 2015.

- Hunter DJ, Zhang W, Conaghan PG, et al. Systematic review of the concurrent and predictive validity of MRI biomarkers in OA. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:557-88.

- Ryzewicz M, Peterson B, Siparsky PN, et al. The diagnosis of meniscus tears: the role of MRI and clinical examination. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007;455:123-33.

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Australian Atlas of Healthcare Variation. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2015 (accessed 15 July 2016).

- Buchbinder R, Harris IA, Sprowson A. Management of degenerative meniscal tears and the role of surgery. BMJ 2015;350:h2212.

- Carr A. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee: Overused, ineffective, and potentially harmful. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1223-4.

- Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1097-107.

- Moseley JB, O'Malley K, Petersen NJ, et al. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 2002;347:81-8.

- Ringdahl E, Pandit S. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am Fam Physician 2011;83:1287-92.

- Wagemakers HPA, Luijsterburg PAJ, Heintjes EJ, et al. Outcome of knee injuries in general practice: 1-year follow-up. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:e56-e63.

- Kise NJ, Risberg MA, Stensrud S, et al. Exercise therapy versus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative meniscal tear in middle aged patients: randomised controlled trial with two year follow-up. BMJ 2016;354:i3740.

- Hawkeswood J, Reebye R. Evidence-based guidelines for the nonpharmacological treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. BCMJ 2010;52:399-403 (accessed 8 March 2017).