Key points

- Mental health problems in young people are extremely common. More than 50% of young people will experience some form of mental ill health by the age of 25.

- Early intervention with effective support and treatment is essential to reduce potential chronicity of mental illnesses. 75% of adult mental health disorders have their onset before the age of 25.

- Personal connections between the young person, their supports and the health professional, a focus on the person's needs rather than their diagnosis, and shared goals are essential for good engagement.

- Regular, scheduled follow-up sessions can be very helpful as they demonstrate to the young person that you are invested in their wellbeing.

- Evidence-based treatments are available, but not equally readily accessible for young people. Work with the young person to determine most suitable treatments based on their needs and preferences and to optimise meaningful engagement.

Mental health is a key component of overall health and wellbeing and a national health priority area.2,3 The majority of mental health problems start in childhood and adolescence. More than 50% of young people will experience some form of mental ill health by the age of 254-6, with 75% of adults with a mental health disorder experiencing the onset of the problem before the age of 25 years.7

The high prevalence of mental health problems, their negative impact on educational, occupational, and social functioning, as well as quality of life, and their significant financial and societal cost, emphasise the need for optimising the management of mental health in young people.2,8

Helping young people to navigate and successfully participate in management and treatment for their mental health issues can be complex, and time-consuming. It is also highly rewarding - improving their current and long-term wellbeing and engagement with society, as well as reducing the risks of substance abuse, depression and suicidal attempts.9 Mental health disorders can lead to life-long social and economic disadvantage. This can be prevented by effective, early treatment. In this article, we address some of the steps GPs can take to help young people engage with support and plan management options to meet their needs and goals.10

What can help make a positive first meeting?

The first contact Jordan has with a health professional can be critical in their longer-term engagement with treatment and services. It is crucially important to build initial rapport, seek to understand the young person’s primary needs and develop a collaborative plan for ongoing contact.11

Ideally, first contact should focus on engagement in a non-stigmatising setting, with a view to early intervention and prevention.12,13 Ways to make Jordan feel comfortable may include:

- Show them they are valued as an individual. For example, the GP could ask Jordan their preferred pronouns, how they wish to be addressed and learn about their hobbies and future plans. This information can be used to discuss how the problems Jordan is experiencing are stopping them from doing what they enjoy and wish to achieve.

- Consider the situation from the young person's perspective. What they see as their primary problem may be different to what is observed by the GP, or what their parents see, and may be a source of disagreement. In Jordan’s case for example, is it their low mood, conflict with friends, or fears about getting COVID-19 that is the primary concern?

- Establish recovery goals. Ask Jordan what would need to change for them to feel ok again. They may say something like “I just don’t want to feel sad and scared all the time”. Ask curious questions around what this would look like.

- Find common elements which can be drawn together to create a shared goal. With a focus on understanding Jordan’s needs, support can be targeted, such as linking in with a psychologist to discuss their low mood or providing education on how to reduce COVID-19 risks. These targeted ‘wins’ can help establish trust, give Jordan and their parents hope, and support the GP getting to know Jordan.

- Use objective measures of severity, such as rating scales for anxiety and depression, which can be done collaboratively. These can be very helpful in planning and monitoring response to treatment.

Depression and anxiety in young people

Depression and anxiety can often present differently in young people, compared to what a GP might typically see in adults.13-15 Young people often describe their distress through how their symptoms are impacting their life, and their ability to function. Many diagnostic categories are based on observations of older people with established illnesses and are not necessarily relevant to young people who are starting to develop symptoms.

How depression or anxiety might present in a young person:13, 15, 16

- Feeling anxious, panicky or on edge most of the time

- Increase in physical symptoms with no medical causes identified (eg, generally feeling unwell, headaches, racing heart, muscle tension, hands shaking)

- Withdrawing from, or avoiding situations (eg, school, socialising)

- Intrusive thoughts

- Feeling irritable, sad or depressed most of the time

- Having thoughts of being worthless

- Inability to concentrate affecting school, work or capacity to enjoy conversations

- Lethargy, lack of motivation and lack of enjoyment in previously enjoyed activities

- Thinking that life is not worth living – sometimes even about suicide

- Harming self (eg, cutting, burning)

- Changes to sleep and appetite

GP relationships as essential connections

When young people reach out for help, they describe the importance of connecting with someone who cares about them.5 This is often demonstrated through continuity of care, following through on actions and remembering small personal details about them.

Research by Tindall et al (2018) explored experiences of help-seeking for first episode psychosis among young people, their care-givers and health professionals.12 Findings from this qualitative study demonstrated how important the relationship between a young person and their GP can be for them to access help.

“[GP] actually made me feel a lot better about going to speak to someone because I think she really cared. And my GP she always texts me and so we have a really good relationship too. I think she pushed me to get help.”

Conversely, young people also described how they feel when realising a health professional appeared to be out of their depth.

“[GP] wasn’t very helpful. She kind of just was like ‘Right. I don’t know how to handle you, but I know that the mental health place can’. So, she just called them and made me wait for a few hours . . .And then she sent me home I’m pretty sure, and I saw them the next day, I think. It felt horrendous. I felt really like upset.”

What can help create a connection when the patient is a young person?

- Connect relationally. Young people often report being more able to open up to health professionals who connect with them person-person, with humour, or over shared interests.

- Where possible, slow down, make eye contact with the young person and be present.

- Demonstrate an interest in the young person, book in regular appointment times and remember details about them as a person.

- Be aware of stigma, self-stigma and shame, and the impacts this could have on the young person’s capacity to open up.

- Ask the difficult questions about risks and vulnerabilities in a caring manner, whilst acknowledging and parking one’s own anxieties. Sometimes, reframing a “Risk Assessment” as a “Safety Assessment” can be helpful.

- Take a needs-based and strengths-based approach rather than a diagnostic approach. Focus on their specific symptoms and problems, as this helps them feel listened to, and it allows the GP time to undertake a more longitudinal assessment.

- Ask about their ways of coping – many young people are very resilient and helping them to use their own strategies can empower them.

- If caregivers are involved, keep them informed of the help-seeking process and talk with the young person about the level of personal information they would like shared with their caregivers.

Accessing care

Ideally support should be financially accessible, with a choice of evidence-based treatments, and include opportunity for family support and engagement. A young person should feel able to speak to someone, to express their discomfort or distress with the experiences they are having, long before their symptoms increase in intensity. However, there are a number of potential barriers (person-, environment- or service-related) that a young person such as Jordan might need to overcome before they can access mental health services, or treatment (Box 1). In some cases, GP knowledge of the health care system, or of available local services, may be able to help address barriers affecting access to care.

|

Box 1: Potential barriers a young person may experience that can impact their ability to access mental health care Lack of awareness about mental illness and support options Shame, stigma or self-stigma Differing cultural understandings of mental illness Lack of cultural safety Lack of infrastructure (internet, hardware) to facilitate online treatment Language barriers Logistical and geographical barriers, including lack of transport to onsite appointments Difficulty attending scheduled appointment times, especially when mental health symptoms are impacting motivation, sleep and energy levels Long waiting lists impacting motivation to seek help Poor experiences during previous help-seeking episodes (eg, attending an emergency department, involvement of police, use of the Mental Health Act) |

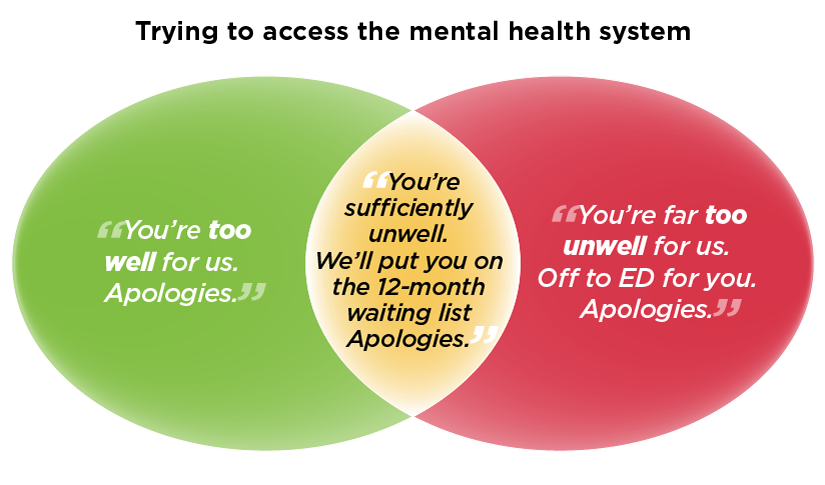

Young people do not always engage well with more traditional medical/clinic-based approaches to treatment. They may fall victim to the “gaps” that exist between primary and specialist services (Figure 1), or between child/ adolescent, and adult services, which have very different origins, and approaches to treatment, as well as set thresholds for treatment.17 The recent development of more specialist Youth Mental Health services is intended to help bridge these gaps, but may not be available in all areas.

Figure 1. Anecdotal experience of person trying to access mental health system.

(Adapted from Twitter – author unknown)

What treatments can help a young person experiencing depression and/or anxiety?

Current evidence supports a staged approach to treatment.13 For young people, especially those with milder presentations, effective first-line treatment could include providing information, suggesting dietary and lifestyle modifications, and encouraging increasing physical activity and exercise.13, 18

For presentations of mild to moderate anxiety or depression CBT has demonstrated benefits and is considered appropriate first line treatment.13,19 Depending on the young person’s personal preferences and needs, interpersonal therapy and non-directive supportive therapies are other evidence-based options for psychological support.19 If there are known waiting periods for accessing psychology or other therapies, work with the young person to explore interim approaches. These could include online mental health programs and resources that can help the young person start to understand their symptoms and distress, while providing some initial support.20

Other useful management strategies can be providing youth-friendly information on mental health and discussing the pros and cons of different treatment approaches.

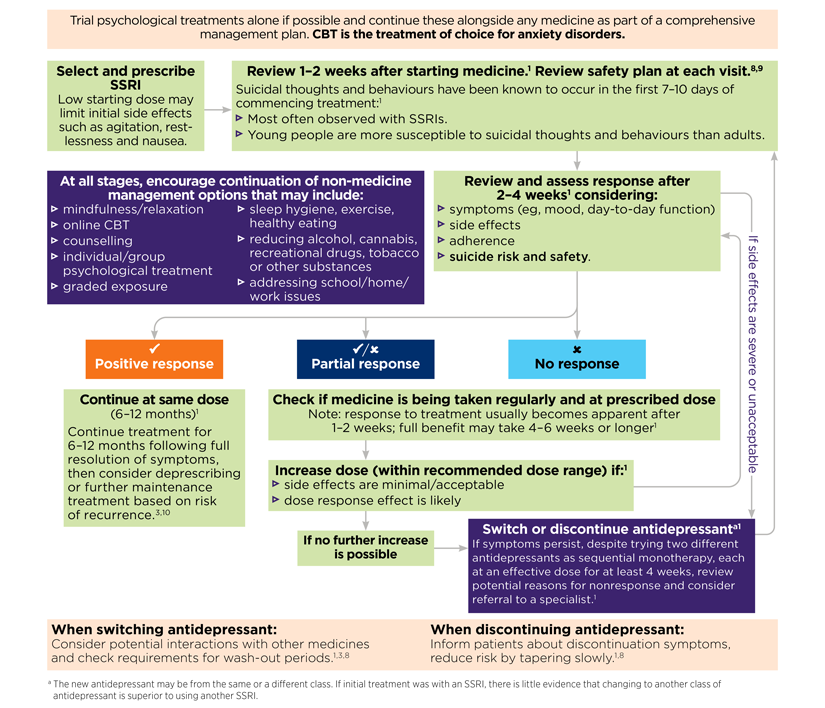

If symptoms of depression or anxiety are severe, or psychological treatment is not possible or not effective, then use of a medicine may be an option. Any use of medicines should be a thoughtful decision made jointly with the young person (and where appropriate their parents or other carer). “Start low and go slow” is a good approach, reviewing the patient regularly to assess their response to, and tolerance of, any drug treatment (Figure 2).

SSRIs, for example, are more effective in moderate to severe depression and anxiety, but risk increasing suicidal thoughts and actions in young people. Increasing doses above the “standard” dose does not result in increased efficacy, but may lead to increased numbers dropping out of treatment due to side effects.21

Other antidepressants, such as SNRIs, or tricyclics and tetracyclics (mirtazapine) are not recommended for young people (particularly those under 18yrs), other than perhaps in specialist practice, due to potential worsening of outcomes.

Figure 2. Algorithm describing approach to selecting a medicine to trial, if required. (References are available at nps.org.au/mental-health-young-people-visiting-refs)

Resources and further information

beyondblue Anxiety and depression in young people- What you need to know

Black Dog Institute Resources

headspace online and phone services

Orygen Factsheets and resources

RANZCP Resource for service users

ReachOut Resources for young people

The Columbia Lighthouse Project Columbia Suicide Risk Assessment

Contributing authors

Iain Macmillan

Iain is a psychiatrist who has been working in the field of youth mental health and early intervention since 2003. He is consultant to the headspace Early Psychosis team in Frankston, Victoria. He is a member of the RANZCP Bi-national Committee of the Section for Youth Mental Health.

Lucy Mahony

Lucy is a youth peer support worker with the Frankston headspace Early Psychosis team. She works with young people to help them find meaning in their experiences and navigate the system. As a Recovery Educator with headspace Discovery college, Lucy draws on her lived experience to help codesign and deliver mental health courses for youth.

Rachel Tindall

Rachel is a mental health nursing lead, working on the codesign and implementation of mental health services at Barwon Health, Victoria. Her PhD, completed in 2020, focused on understanding how young people, their caregivers and their clinicians experience engagement with, and disengagement from, public mental health services.

References

- Crandon TJ, Scott JG, Charlson FJ, et al. A social–ecological perspective on climate anxiety in children and adolescents. Nature Climate Change 2022:1-9.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Mental health. Australia's health: Snapshots. Canberra: AIHW, 2020 (accessed 29 April 2022).

- AIHW & Department of Health and Family Services. First report on the National Health Priority Areas, full report. Canberra: AIHW, 1997.

- Caspi A, Houts RM, Ambler A, et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Mental Health Disorders and Comorbidities Across 4 Decades Among Participants in the Dunedin Birth Cohort Study. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203221.

- Copeland W, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, et al. Cumulative prevalence of psychiatric disorders by young adulthood: a prospective cohort analysis from the Great Smoky Mountains Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011;50:252-61.

- Gibb SJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Burden of psychiatric disorder in young adulthood and life outcomes at age 30. Br J Psychiatry 2010;197:122-7.

- Kessler R, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:593-602.

- Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, et al. The mental health of children and adolescents. Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2015.

- Scott J FD, McGorry P, Birchwood M, Killackey E, Christensen H,. Adolescents and young adults who are not in employment, education, or training. BMJ 2013;347:f5270.

- Tindall R, Francey S, Hamilton B. Factors influencing engagement with case managers: Perspectives of young people with a diagnosis of first episode psychosis. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2015;24:295-303.

- Tindall RM, Simmons MB, Allott K, et al. Essential ingredients of engagement when working alongside people after their first episode of psychosis: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Early Interv Psychiatry 2018;12:784-95.

- Tindall R AK, Simmons MB, Roberts W,. Engagement at entry to an early intervention service for first episode psychosis: an exploratory study of young people and caregivers. Psychosis 2018;10:175-86.

- Malhi GS, Bell E, Bassett D, et al. The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2021;55:7-117.

- Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, et al. Depression in adolescence. Lancet 2012;379:1056-67.

- Beyond Blue. Anxiety and depression in young people. What you need to know.

- The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne. Engaging with and assessing the adolescent patient. Parkville, Victoria: The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne, 2019.

- McLaren S, Belling R, Paul M, et al. 'Talking a different language': an exploration of the influence of organizational cultures and working practices on transition from child to adult mental health services. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:254.

- Purcell R, Ryan S, Scanlan F, et al. A guide to what works for depression in young people. 2nd ed. Beyond Blue Ltd, 2013.

- Australian Psychological Society. Evidence-based psychological interventions in the treatment of mental disorders: A review of the literature 2018.

- Lehtimaki S, Martic J, Wahl B, et al. Evidence on Digital Mental Health Interventions for Adolescents and Young People: Systematic Overview. JMIR Ment Health %G English 2021;8:e25847.

- Furukawa TA, Cipriani A, Cowen PJ, et al. Optimal dose of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, venlafaxine, and mirtazapine in major depression: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2019;6:601-9.