Key points

- The faecal calprotectin test is highly effective in differentiating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) from irritable bowel syndrome.

- It is also an effective, non-invasive tool for monitoring disease activity during treatment for patients with known IBD.

- An MBS item for general practitioners to order a faecal calprotectin test will be introduced in November 2021. A separate MBS item will allow gastroenterologists to perform a follow-up test if the initial findings are unclear.

- Patients with elevated faecal calprotectin levels should be promptly referred to a gastroenterologist.

- Corticosteroids are not a maintenance treatment for IBD. Patients experiencing more than 1 flare per year should be referred to their gastroenterologist for escalation of treatment.

The challenges of IBD in primary care and beyond

Early intervention and intensive monitoring are essential to achieve tight control of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The goals of IBD management are firstly to induce remission, and then to maintain remission, preventing disease progression and avoiding hospitalisation and surgery. This approach requires timely diagnosis and specialist referral, and effective ongoing coordinated care.

NPS MedicineWise brought together health professionals involved in the diagnosis and management of IBD for a round table discussion in May 2021.

The panel consisted of a specialist IBD gastroenterologist, a gastroenterologist and a general practitioner (GP), who each shared their perspective on some of the common challenges faced when distinguishing IBD from other bowel disorders in primary care and providing optimal care for patients with IBD.

Meet the panel

IBD Gastroenterologist

A/Prof Susan Connor

Liverpool Hospital, Sydney

Gastroenterologist

Dr Michael De Gregorio

St Vincent's Hospital, Melbourne

General practitioner

A/Prof Morton Rawlin

Melbourne

Case study 1: The role of faecal calprotectin in diagnosis of IBD

This case involved a 26-year-old man who presented to his GP with a 4 week history of abdominal pain, poor appetite and fatigue. He reported 3–4 episodes of watery diarrhoea each day. The patient had no significant medical history and had not recently travelled overseas.

Clinical features suggestive of IBD

Many intestinal disorders present with similar symptoms; distinguishing patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) from those presenting with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is important.1 It was agreed that although IBD and IBS have several symptoms in common, there are key features that distinguish IBD from IBS that are useful for GPs.

The presence of any new and persistent bowel symptoms or alarm features presented in Table 1 is highly suggestive of intestinal inflammation and warrants further investigation.

Table 1: Signs and symptoms suggestive of IBD1,2

|

Features |

IBD |

IBS |

|

Weight loss |

Yes |

No |

|

Blood in stools |

Yes |

No |

|

Nocturnal diarrhoea (especially if wakes patient from sleep) |

Yes |

No |

|

Fever |

Yes |

No |

|

History |

Short |

Long |

|

Bloods |

Abnormal High WCC, platelets, ESR, CRP Low Hb, albumin, Fe studies |

Normal |

|

Faecal calprotectin |

Elevated |

Normal |

Although there were no alarm features requiring urgent referral to a gastroenterologist, it was agreed that initial investigations including blood tests and faecal calprotectin testing were warranted in this case.

The role of faecal calprotectin in diagnosis of IBD

It was highlighted that there is no single test to reliably diagnose all cases of IBD however the faecal calprotectin test is highly accurate in discriminating between IBD and IBS. This can be particularly useful in low risk patients without clinical alarm features, potentially avoiding the need for more expensive and invasive tests.

Faecal calprotectin is a neutrophil-derived protein biomarker.1 It is a highly sensitive, non-invasive marker of intestinal mucosal inflammation and has been shown to be useful for differentiating between people with and without current active inflammation in the lower intestine needing further evaluation.1,3,4

It was noted that the very high negative predictive value (100%) of the faecal calprotectin test for IBD makes it an extremely useful, non-invasive tool for differentiating IBD from non-inflammatory bowel disorders.4

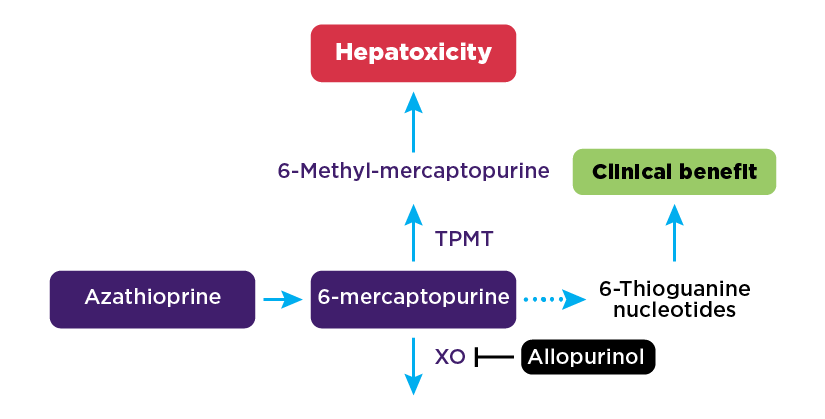

A patient with a normal faecal calprotectin (less than 50 micrograms/g), in the absence of clinical alarm symptoms, can be confidently diagnosed with IBS, requiring no further testing or specialist referral (see Figure 1).4

Faecal calprotectin concentrations between 50 and 100 micrograms/g are considered borderline and patients with clinical symptoms suggestive of IBD require retesting in 2 weeks (see Figure 1).

Elevated faecal calprotectin (above 100 micrograms/g) suggests there is active inflammation within the gastrointestinal system and should trigger a referral to a gastroenterologist for further investigation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: IBD vs IBS: Role of faecal calprotectin1

In this case, the patient’s initial faecal calprotectin test result was 90 micrograms/g. It was recommended to repeat the test in 2 weeks, which showed a result of 150 micrograms/g and warranted immediate referral to a gastroenterologist for further investigation.

Case study 2: First-line therapy and monitoring

This case involved a 38-year-old woman with symptoms of recurrent and nocturnal diarrhoea and rectal bleeding, fever, nausea and weight loss. Initial investigations showed a faecal calprotectin of 190 micrograms/g and the patient was referred urgently to a gastroenterologist. Following endoscopic investigation, she was diagnosed with Crohn disease. The patient was otherwise healthy and was planning a second pregnancy.

Induction of remission and the role of thiopurines

Oral corticosteroids are used to induce remission in moderate to severe active Crohn disease1,5 but it was reinforced that these are not recommended for maintenance therapy and should be slowly weaned over at least 6 weeks.

The panel discussed the role of immunomodulators in maintaining steroid-free remission, identifying thiopurines as the preferred first-line treatment for Crohn disease.5 The clinical effect delay of 2 to 3 months means these agents play a limited role in inducing remission and it was recommended to commence thiopurines at the same time as corticosteroids.1

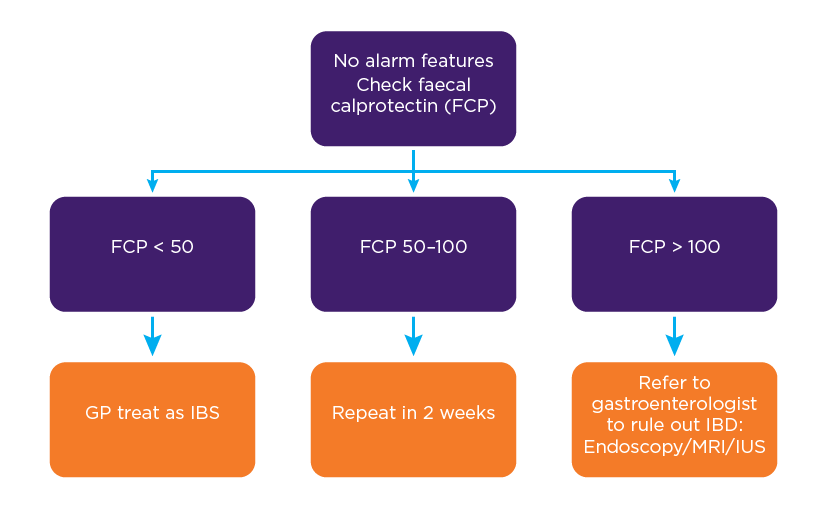

The importance of thiopurine s-methyltransferase (TPMT) activity testing before starting treatment with thiopurines was raised. TPMT is a key enzyme in the metabolism of thiopurines and variation in TPMT activity regulates thiopurine toxicity and therapeutic efficacy. Patients with reduced TPMT activity are at high risk of developing severe myelosuppression when treated with standard doses of thiopurines, while patients with normal TPMT activity can be initiated on standard dosing.1

The increased risk of infection and cancer associated with thiopurines was discussed. Although the risks are important to be mindful of, they are still very low in comparison to the risks from uncontrolled disease, which can lead to hospitalisation, surgery and reduced quality of life. For example, the annual incidence of lymphoma in the general population is 3 in 10,000 and with immunosuppression, the annual incidence still remains very low at approximately 5 in 10,000.6-8

To minimise the risk of preventable infections, vaccinations are ideally given before initiating thiopurines, as well as checking serologies for treatable infections. In addition to assessing immunity to vaccinatable infections, it’s important to perform baseline serologies for hepatitis C, Epstein Barr and human immunodeficiency virus.9

Ensuring patients are up to date with age-appropriate cancer screening and educating them about skin cancer prevention,10 is also important, with the panel recommending a baseline skin check and annual skin checks thereafter.

Thiopurines can be used safely in pregnancy and breastfeeding under the supervision of a gastroenterologist11,12 and would be the treatment of choice for the patient in this case.

Low-dose methotrexate for Crohn disease

Low-dose methotrexate is an alternative maintenance therapy for Crohn disease, but the limited efficacy data means it is generally used for patients who are intolerant of, or have contraindications to, thiopurines.5,13,14

Subcutaneous or intramuscular methotrexate has superior efficacy compared with oral methotrexate.13,14

Low-dose methotrexate, as used in Crohn disease, is not considered chemotherapy. The panel emphasised the importance of addressing this with patients to improve adherence.

Methotrexate is teratogenic during the first trimester of pregnancy so it was reinforced that it would not be a suitable option for this patient who wants to fall pregnant. Women prescribed methotrexate should use contraception while on treatment and cease methotrexate at least 3 months before planning to conceive.

Monitoring

Once treatment with immunomodulators has started, the panel agreed that proactive monitoring is essential to evaluate treatment response, detect complications related to disease or treatment, and identify and treat recurrent disease early.

After starting thiopurines, each patient’s full blood count and liver function tests should be performed to detect myelosuppression and hepatotoxicity at the following intervals:

- weekly for the first month

- fortnightly for the second month

- monthly for the third month

- every 3 months long-term once on a stable dose.1

To evaluate treatment response, clinicians are recommended to use a combination of patient symptoms and bio-inflammatory markers.

Faecal calprotectin is a highly specific and sensitive test for detecting active disease, including sub-clinical disease activity, and strongly correlates with mucosal inflammation. During active disease, monitoring of faecal calprotectin was recommended every 3 months, and moving to every 6 months once in remission.1

Disease activity is assessed endoscopically and radiologically by gastroenterologists at 6–12 months of treatment to evaluate mucosal healing and deeper states of disease remission.

Once in remission, patients should be reviewed every 3 to 6 months. The use of faecal calprotectin to proactively monitor patients and detect disease relapse early was discussed. It was highlighted that faecal calprotectin levels start rising approximately 3 months before the onset of clinical symptoms.16 An elevated faecal calprotectin warrants urgent gastroenterologist review for consideration of further investigation and treatment escalation. Intestinal ultrasound, which is easily performed in an outpatient setting, was discussed as a tool to detect disease recurrence with high sensitivity and specificity, allowing treatment escalation in a timely manner.3

GPs play a critical role in health care maintenance, including:

- monitoring for treatment complications

- cancer: annual skin checks and age-appropriate cancer screening

- infection: ensure vaccinations are up to date.

- monitoring for disease complications

- osteoporosis: regular bone density checks

- mental health, as patients with IBD are at high risk of mental health issues

- nutritional health.

Pregnancy and IBD

It was noted that common misconceptions about IBD, pregnancy and the safety of drugs in pregnancy, leads to a high rate of voluntary childlessness. Patients should be reassured that the chance of their children having IBD is low. The key to having a successful pregnancy is to have good disease control, ideally remission, prior to conception.

IBD medication safety during pregnancy and breastfeeding was discussed, highlighting that most medications are safe to use during pregnancy, with the exceptions of allopurinol and methotrexate.11 The patient presented in this case study was recommended to see her gastroenterologist and continue the prescribed thiopurine to keep her disease under control throughout her pregnancy. Closer monitoring by her gastroenterologist will be required as pregnancy may alter thiopurine metabolism.

Case study 3: Treatment adherence and flare management

The final case presented a 49-year-old man who had been diagnosed with ulcerative colitis 2 years ago. He discontinued topical aminosalicylates (5-ASA) due to the mess associated with liquid enemas and has been taking oral mesalamine. He had a flare 6 months ago and is again experiencing worsening of symptoms with nocturnal diarrhoea, blood in his stools and a fever. The patient’s comorbidities include gout, for which he is prescribed allopurinol.

Managing a disease flare

The key steps to managing a flare of ulcerative colitis were outlined, including performing a faecal calprotectin test and excluding infection. Optimising the dose and adherence to first-line oral and rectal 5-ASA therapies is essential, as the combination of oral and rectal 5-ASAs is the most effective treatment compared to either agent alone.17,18 Exploring the barriers to adherence to topical 5-ASA treatments, and providing further education and counselling about the use of these treatments is essential for this patient.

This is the patient’s second flare in a 12-month period and it was noted that a referral to a gastroenterologist is warranted for further evaluation and treatment escalation.

Diet and IBD

3 key points relating to IBD and diet were discussed:

- Inducing disease remission: The lack of evidence for dietary therapy as a treatment for an IBD flare was discussed, other than for Crohn disease where Exclusive Enteral Nutrition (EEN) and the Crohn Disease Exclusion Diet (CDED) have been shown to be as effective as corticosteroids.19,20

- Maintaining disease remission: A healthy well-balanced diet in line with current Australian healthy eating guidelines is recommended by the panel during remission of IBD, including high-fibre containing foods such as fruit, vegetables and wholegrains.21 A low-fibre diet may be necessary when strictures are present in Crohn disease, otherwise a healthy well-balanced diet including fibre is recommended when patients are in remission.

- Avoiding malnutrition: It is important to counsel patients about food avoidance or restrictions which can lead to malnutrition. Refer patients who are reporting food-related symptoms to a dietitian, particularly an IBD dietitian if available, for further assessment.

Regular exercise, reducing alcohol intake and smoking cessation were also highlighted as important lifestyle factors that may be protective for IBD and should be addressed with this patient.

Treatment escalation

The importance of both symptoms and bio-inflammatory markers for monitoring treatment response was discussed. It was recommended that an immunomodulator should be introduced to maintain remission and reduce the need for future corticosteroids. Although the efficacy data for ulcerative colitis is not as robust as for Crohn disease, an immunomodulator increases steroid-free remission rates.18 Thiopurines are the preferred agent as there is less data about the effectiveness of methotrexate in treating ulcerative colitis.13

The patient in this case study is prescribed allopurinol for gout and it was noted that allopurinol shifts metabolism of thiopurines away from 6-MMP towards 6-TGN.15 The panel recommended introducing thiopurines at a lower dose and monitoring closely for adverse drug reactions.

The recommended treatment target in ulcerative colitis is mucosal healing, as this improves long-term remission rates and reduces the risk of colectomy. Faecal calprotectin can be used as a surrogate marker of mucosal inflammation and performed 3 months after thiopurine initiation to evaluate treatment response. Endoscopic evaluation will typically be considered from 6 months for histological evidence of mucosal healing.

If this patient’s symptoms and/or bio-inflammatory markers continued to worsen despite therapeutic levels of thiopurine metabolites, it was agreed that it is essential for a gastroenterologist to be involved for escalation of treatment to biologics and/or small molecules. The key message was to avoid prescribing recurrent courses of corticosteroids. If the patient is having more than 1 flare per year, they need to be referred to their gastroenterologist for therapy escalation.

Summary

The 3 cases presented in the roundtable discussion provide insight into best practice for management of IBD. Prompt gastroenterologist referral for patients who have bowel symptoms with alarm features or an elevated faecal calprotectin level is warranted for timely evaluation of possible IBD and early treatment initiation. For patients with an established diagnosis of IBD, regular proactive monitoring is essential to evaluate treatment response and also detect complications and identify early disease recurrence. Good coordination and communication between GPs and gastroenterologists underpins safe and high quality care for patients with IBD.

Useful resources

For health professionals

NPS MedicineWise

- Webinar: IBD: diagnosis and management in primary care and beyond

Join an interdisciplinary panel as they consider some of the challenges faced in the diagnosis and management of patients with IBD.

- Webinar: Chronic abdominal pain: could it be irritable bowel syndrome?

Listen to an interdisciplinary panel discuss some of the challenges that can arise in general practice when a patient presents with chronic, non-specific abdominal pain.

- Gastroenterology conditions for health professionals

Up-to-date information and tools for gastroenterologists, GPs and other health professionals to optimise the safety and health outcomes of biological and other specialised medicines for IBD.

Gastroenterological Society of Australia (GESA)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinical Update for General Practitioners and Physicians (Updated 2018)

This provides a general guide to appropriate practice in the management of IBD, based on the best available evidence and international consensus statements. - Pregnancy, fertility and IBD gastroenterologist fact sheet

This resource provides gastroenterologists with guidance for preconception, monitoring during pregnancy, flare management and medication safety during pregnancy and lactation. - Pregnancy, fertility and IBD GP and obstetrician fact sheet

This resource provides information about medication safety, preconception safety and monitoring during pregnancy. - IBS4GPS

This online tool for GPs provides guidance for clinical assessment, investigation and management of IBS.

For your patients

NPS MedicineWise

- Thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease

This action plan explains the benefits and risks of these medicines for IBD, and the importance of regular checks with the health care team. - Low-dose methotrexate for Crohn’s disease

This action plan explains the facts about taking low-dose methotrexate. - Deciding on the best way to use my ulcerative colitis medicines

Use this decision aid to support decision making about the use of oral and rectal 5-ASAs.

Crohn’s & Colitis Australia

Gastroenterological Society of Australia (GESA)

Expert reviewer

Dr Michael De Gregorio is a consultant gastroenterologist and an inflammatory bowel disease clinician-research fellow at St Vincent's Hospital, Melbourne.

In 2020 he became a fellow of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians and was awarded an Australian Commonwealth Government scholarship to undertake a PhD at the University of Melbourne. His research focuses on the optimisation of surgical and medical management in perianal fistulising Crohn's disease, with an interest in biologic drugs and therapeutic drug monitoring.

He was central in the development of a new coordinate multidisciplinary care model for patients with perianal fistulising Crohn's disease at St Vincent's.

References

- Gastroenterological Society of Australia. Cinical update for general practitioners and physicians: Inflammatory bowel sisease. Melbourne: GESA, 2018 (accessed 9 February 2021).

- Wright EK, Ding NS, Niewiadomski O. Management of inflammatory bowel disease. Med J Aust 2018;209:318-23.

- Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, et al. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis 2019;13:144-64.

- An YK, Prince D, Gardiner F, et al. Faecal calprotectin testing for identifying patients with organic gastrointestinal disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Med J Aust 2019;211:461-7.

- Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, et al. Ecco guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn's disease: Medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis 2020;14:4-22.

- Siegel CA, Marden SM, Persing SM, et al. Risk of lymphoma associated with combination anti-tumor necrosis factor and immunomodulator therapy for the treatment of Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:874-81.

- Kotlyar DS, Lewis JD, Beaugerie L, et al. Risk of lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:847-58 e4; quiz e48-50.

- Lemaitre M, Kirchgesner J, Rudnichi A, et al. Association between use of thiopurines or tumor necrosis factor antagonists alone or in combination and risk of lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JAMA 2017;318:1679-86.

- Warner B, Johnston E, Arenas-Hernandez M, et al. A practical guide to thiopurine prescribing and monitoring in IBD. Frontline Gastroenterol 2018;9:10-5.

- Hagen JW, Pugliano-Mauro MA. Nonmelanoma skin cancer risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease undergoing thiopurine therapy: A systematic review of the literature. Dermatol Surg 2018;44:469-80.

- Gastroenterological Society of Australia. IBD medication safety during pregnancy and lactation. Melbourne: GESA, undated (accessed 15 May 2021).

- Restellini S, Biedermann L, Hruz P, et al. Update on the management of inflammatory bowel disease during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Digestion 2020;101 Suppl 1:27-42.

- Nielsen OH, Steenholdt C, Juhl CB, et al. Efficacy and safety of methotrexate in the management of inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. EClinicalMedicine 2020;20:100271.

- Patel V, Wang Y, MacDonald JK, et al. Methotrexate for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD006884.

- de Boer NKH, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Jharap B, et al. Thiopurines in inflammatory bowel disease: New findings and perspectives. J Crohns Colitis 2018;12:610-20.

- Reenaers C, Bossuyt P, Hindryckx P, et al. Expert opinion for use of faecal calprotectin in diagnosis and monitoring of inflammatory bowel disease in daily clinical practice. United European Gastroenterol J 2018;6:1117-25.

- Marteau P, Probert CS, Lindgren S, et al. Combined oral and enema treatment with Pentasa (mesalazine) is superior to oral therapy alone in patients with extensive mild/moderate active ulcerative colitis: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study. Gut 2005;54:960-5

- Harbord M, Eliakim R, Bettenworth D, et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 2: Current management. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:769-84.

- Levine A, Sigall Boneh R, Wine E. Evolving role of diet in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut 2018;67:1726-38.

- Levine A, Wine E, Assa A, et al. Crohn's disease exclusion diet plus partial enteral nutrition induces sustained remission in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2019;157:440-50 e8.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013 (Accessed 30 June 2021).