Shared care approaches to rheumatoid arthritis: supporting early and sustained methotrexate

Rheumatoid arthritis treatment has been revolutionised by the use of DMARDs like methotrexate. Shared care from a team of health professionals can optimise treatment and improve patient outcomes.

Key points

- Methotrexate is the gold standard for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treatment. It can reduce symptoms, limit disease progression and bring RA into clinical remission.

- There is a small ‘window of opportunity’, possibly as short as 3 months, during which therapy has the most impact. Urgent referral to a rheumatologist, and early diagnosis and treatment initiation is essential.

- Consistent messaging from all healthcare professionals can address patient concerns about methotrexate.

- Structured collaboration between patients, GPs, rheumatologists and other healthcare professionals can support an earlier start to treatment, better adherence and better outcomes.

Many factors contribute to achieving the best possible outcomes for patients with RA, some of which we will examine in this article. What is a ‘good referral’ from a GP to enable early diagnosis and treatment initiation? What support can a rheumatologist give GPs for the management of RA patients? What are the practice gaps that need closing?

Download and print

Low-dose methotrexate for RA

Conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) are the cornerstone of RA treatment, and can minimise or prevent joint damage and induce clinical remission in RA patients.1 Based on efficacy, safety, cost, ability to individualise dose and method of administration, the csDMARD methotrexate is the recommended first-line DMARD for most patients with RA.2,3 Approximately 40% of patients respond to methotrexate monotherapy (using the American College of Rheumatology 50 response criterion),4 with higher response rates possible in combination with other DMARDs,4 albeit with higher risk of adverse effects.2

The 3-month window of opportunity

Prompt diagnosis of RA and early treatment initiation with disease-modifying therapy are crucial to prevent irreversible joint damage.1 Patients with early arthritis who are referred to a specialist within 3 months of disease onset are more likely to experience drug-free remission, have less joint damage seen on X-ray, and have less need for orthopaedic surgery compared to patients referred at a later stage.5

Guidelines recommend methotrexate for the initial treatment of RA (alternative csDMARDs may be used if methotrexate is contraindicated).1,2,6 Corticosteroids, which provide fast-acting symptomatic relief and have disease-modifying properties,1 can be considered at initiation while awaiting a response to csDMARD therapy. However, due to safety issues with long-term use,1 they should be tapered as rapidly as clinically possible (usually within 3 months, and within 6 months in exceptional cases).1,2,6

Clinical remission is the treatment goal

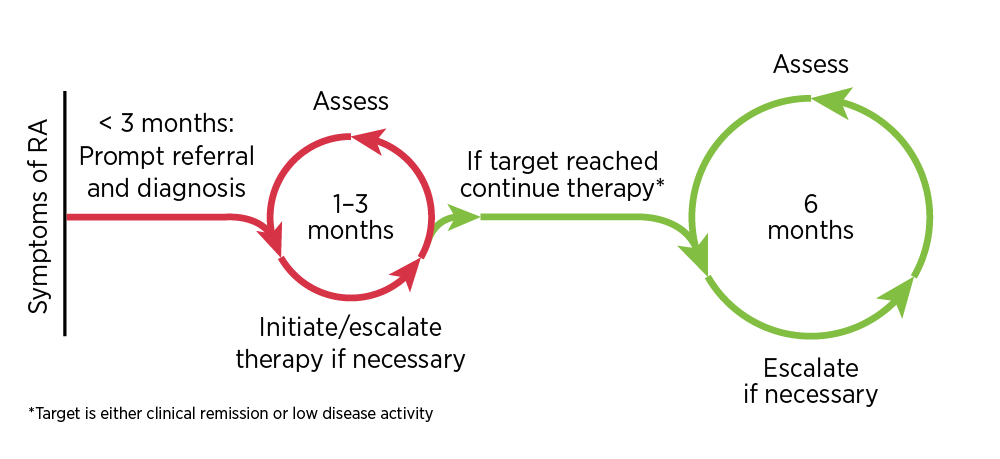

Guidelines recommend a ‘treat to target’ strategy involving regular assessment and adjustment of therapy, including adding and combining DMARDs, to achieve the target of well-controlled disease.1,2,6-8 The target of RA treatment should be clinical remission, or at least low disease activity in long-standing disease.1,2,6-8 Clinical remission is defined by symptom relief, the normalisation of inflammatory markers and the absence of joint swelling.1 Therapy should be adjusted if there is no improvement 3 months after the start of treatment, or if the target has not been reached after 6 months.2

Using this ‘treat-to-target’ strategy, randomised controlled trials show that remission can be achieved for up to 65% of patients, compared with 10%–20% of those treated less intensively.9,10

Shared care: coordinating to maximise the methotrexate benefit

Early referral

‘Facilitating early diagnosis of RA and initiation of treatment is vital,’ says Dr Barrett. ‘GPs are encouraged to expand their experience with RA patients, develop confidence in recognising the clinical features suggestive of RA, and follow up with appropriate tests. Rheumatologists, within both public and private healthcare systems, are working to make themselves available for a timely patient consultation, and provide advice to GPs on interim management if an untimely delay occurs.’

Australian and international guidelines agree that GPs should ‘urgently refer any patient with suspected rheumatoid arthritis to a specialist’.1,2,5,6

To facilitate this, GPs should use rheumatologists’ fast-track triage systems for patients with suspected RA, and they are strongly encouraged to make direct contact with a specialist to expedite referral or to obtain advice on treatment.1

A diagnosis of RA is made on the basis of clinical presentation, in association with autoantibodies and raised inflammatory markers (see box below). These features can assist with effective triaging of patients with inflammatory arthritis.11

An Australian study analysing 200 GP referral letters found that prereferral investigations only appeared in 21% of letters, although almost all rheumatologists (96%) regarded these as important.12

The RACGP recommends that for patients presenting with painful and swollen joints, GPs should support a clinical examination with appropriate tests, including rheumatoid factor and/or anti-CCP antibody tests and inflammatory marker tests.13 Patients with a high RF titre or a positive anti-CCP antibody test, or with sustained inflammatory markers, have poor prognosis and should be intensively managed. Treatment should start as early as possible for all patients with RA.1

‘Prescription of corticosteroids before a referral to a rheumatologist is generally not advisable,’ says Dr Barrett. Use of corticosteroids before a patient sees a rheumatologist can mask clinical features and delay diagnosis,5,9,14 and ideally should only be done under the advice of a specialist.

‘If a patient suspected of RA is functionally impaired to such a degree that corticosteroids are considered, direct contact with a rheumatologist is recommended,’ says Dr Barrett.

Methotrexate myths

‘Unfortunately, due to misinformation, some patients with RA are concerned about the use of methotrexate, seen to them as chemotherapy,’ says Dr Barrett. ‘Much of the information contained in the Consumer Medicine Information (CMI) that is given to the patient at dispensing is irrelevant for the low doses used to treat RA. It is our role to dispel these myths, thereby improving adherence to methotrexate therapy.’

Methotrexate is used as monotherapy in chemotherapy regimens for cancer treatment where single dosages might exceed 1000 mg.15 However, much lower doses (10–30 mg per week) of methotrexate have been used effectively to treat RA since the mid-1980s.15 It is important that all healthcare professionals explain to patients that low-dose methotrexate for RA is not the same as ‘methotrexate for chemotherapy’. It is being used as an immune modifier. Patients on low-dose methotrexate and their body fluids can safely be in contact with others.15

There are also fears about subcutaneous methotrexate, which originate from regulations relevant for its use in cancer treatment. Low-dose subcutaneous methotrexate for the treatment of RA does not need to be prepared by an oncology pharmacist or administered by an oncology nurse, and eye masks and gloves are not required for staff administering low-dose methotrexate. Low-dose methotrexate is neither a vesicant nor an irritant, and there is no extravasation risk. Carers can safely administer low-dose subcutaneous methotrexate, and there is no risk to pregnant workers. Low-dose methotrexate is safe and appropriate for self-administration.15

Finally, low-dose methotrexate can be coprescribed with NSAIDs for those with normal renal function.15

Managing patients with RA on low-dose methotrexate

‘Guidelines for the GP on how to monitor low-dose methotrexate, and manage the patient, including when to refer back to the rheumatologist earlier than the planned review, are the best way to ensure safe use of methotrexate and optimal treatment results,’ says Dr Barrett. ‘Like the referral letter from the GP, good communications with precise instructions in a shared care model, agreed by all parties, are important in coordinating care.’

The Australian Therapeutic Guidelines state that all patients with RA should have an individualised management plan that is negotiated between the patient, their specialist, the GP, and other health professionals involved.1 This plan should address the following key elements.

- Drug toxicity monitoring: Regular monitoring for DMARD adverse effects is needed, including appropriate kidney and liver tests and full blood count. Monitoring is most frequent in the first 3 to 6 months of therapy, and after dose increases when adverse effects are most likely.16

Details about possible adverse drug reactions and the monitoring of DMARDs can be found in Australian Prescriber.3 - Reproductive health: Pregnancy should be avoided while taking methotrexate and some other DMARDs,17 however, based on limited evidence, low-dose methotrexate may be compatible with paternal exposure.18 Treatment options should be discussed if pregnancy is planned.19

Sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine are DMARDs that are compatible with pregnancy.17,20 - Vaccinations: RA and its treatment can increase the risk of infection.1 To minimise the risk of vaccine-preventable infections, ensure up-to-date influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations.16 Vaccination should ideally be performed before starting disease modifying therapy. Most vaccines can be given safely. Current recommendations are that low dose methotrexate (≤ 0.4 mg/kg per week) is not a contraindication to live vaccines, such as Zostavax, MMR (measles, mumps and rubella), oral polio or yellow fever.21,22

- Infection monitoring: Vigilance for infection is important, as febrile response may be blunted.

- Disease activity review: Initial reviews should be performed every 1–3 months for patients with high disease activity. Clinical assessments can be less frequent, such as every 6 months, once the treatment target has been stabilised.2 These assessments should be aligned with regular pathology monitoring as part of shared care.

- Complications: Monitor and manage potential complications including atherosclerosis, osteoporosis, depression, vasculitis, lung disease and neuropathy. Systemic inflammation is the main contributor to the increased risk of developing atherosclerosis for patients with RA, however other risk factors for cardiovascular disease should be actively managed.1

- Other: Advice about management of pain and fatigue and how to treat disease flares should be offered (also see below on corticosteroids and disease flares).1

NPS MedicineWise has developed a clinician-mediated tool for informing and supporting patients starting on low-dose methotrexate.

Further areas for reflection

The role of corticosteroids in RA management

‘Corticosteroids have a role in RA management as a bridge while a csDMARD such as methotrexate is initiated,’ says Dr Barrett. ‘Many patients, however, remain on corticosteroids long-term, where adverse effects are common. A risk-benefit analysis for the individual patient is vital if long-term use is considered, however in general, long-term use is not advocated.’

Corticosteroids have anti-inflammatory and disease-modifying effects with a rapid onset of action.1 Their use is, however, limited to the short term due to a high risk of serious adverse effects including weight gain, hypertension, diabetes, cataracts and osteoporosis.5 They can be used as a bridging therapy when initiating methotrexate (or other csDMARDs), or for short-term treatment of flare-ups,6 but their use should be gradually reduced and ultimately stopped, usually within 3 months.2

‘One of the questions I am most frequently asked by GPs is how to deal with flare-ups,’ says Dr Barrett.

A flare-up is an episode of increased disease activity beyond normal day-to-day variation.25

‘This is a good example of shared care,’ says Dr Barrett. ‘The patient should have a plan for handling flare-ups including using simple analgesics, NSAIDs and non-pharmacological aids. The GP can assess the situation using history, examination and blood tests. If simple analgesia or NSAIDs are ineffective, prescribing corticosteroids for short-term relief may be indicated. If the disease control does not improve, a request for an earlier rheumatology review to reassess the DMARD treatment regime is vital.’

Subcutaneous methotrexate improves tolerability

Analysis of PBS and MBS data (based on dispensed prescriptions) shows that only a small percentage of patients with RA trial both oral and subcutaneous methotrexate before treatment is escalated. Of patients who started a bDMARD or a tsDMARD for RA between January 2015 and December 2016, only 3.3% had trialled both oral and subcutaneous methotrexate in the previous 2 years. (Calculated from data supplied by the Department of Human Services.)

‘I anticipate that with greater awareness of the potential benefits, and education from practice staff on the correct administration, Australian patients will be afforded the opportunity of the increased efficacy and lower incidence of adverse effects of subcutaneous methotrexate,’ says Dr Barrett.

The optimal dosing strategy for methotrexate starts at 15–20 mg/week, with prompt escalation to 25–30 mg/week, or the highest tolerable dose, and a switch to subcutaneous methotrexate for patients with inadequate response or poor tolerance.22,24,26,27 Subcutaneous methotrexate, with a higher bioavailability and lower variability than oral methotrexate,24 is more effective and associated with fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects.24

Folic acid supplementation and methotrexate dosage timing are further methods to improve the tolerability of methotrexate16 (See ‘Prescribing points for methotrexate’ above).

A video demonstrating how a patient can self-administer subcutaneous methotrexate is available.

Maintain methotrexate when intensifying DMARD treatment

If the treatment target is not reached with methotrexate monotherapy, other csDMARDs and subsequently biological DMARDs (bDMARDs) or targeted synthetic DMARDS (tsDMARDs) may be trialled, usually in addition to methotrexate.1,2,6

Despite proven benefits of continuing methotrexate when starting bDMARDs or tsDMARDs, Australian evidence shows that up to a third of patients do not have continuing prescriptions for csDMARDs, including methotrexate.28

There is no consensus on when to begin combination therapy, or on the optimal combination of csDMARDs for patients with RA, but combining csDMARDs is frequently used as a first-line strategy, particularly for those with poor prognostic factors.1,3

The PBS requires that before starting a bDMARD or tsDMARD, patients must have failed a 6-month intensive DMARD treatment trial with a minimum of two csDMARDs, used for a minimum of 3 months each, (including ≥ 20 mg per week of methotrexate, unless contraindicated or not tolerated at required minimum dose).29

All bDMARD and tsDMARD treatments have superior efficacy for the treatment of RA when combined with methotrexate, compared with when used as monotherapy,2 and for some bDMARDS (abatacept, golimumab, infliximab, rituximab), maintaining methotrexate is a PBS requirement for their use.29

Getting the most out of DMARDs for RA

The use of DMARDs, with methotrexate as the backbone of the treatment, has revolutionised RA management, but there is still room to maximise the benefit.

Rheumatologists, GPs, nurses, pharmacists and other allied health professionals can each play a role in improving coordinated care for RA patients. This can help to initiate treatment earlier, keep patients on optimal treatment, and enable regular monitoring to maintain the prolonged benefit of disease-modifying treatment.

Expert reviewers

Dr Claire Barrett

Rheumatologist, Redcliffe Hospital, Queensland

Senior Lecturer, University of Queensland

Associate Professor Morton Rawlin

General practitioner, Templestone

Adjunct Associate Professor, General Practice, University of Sydney

References

- Rheumatology Expert Group. Therapeutic Guidelines: Rheumatoid arthritis. West Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, 2017 (accessed 14 December 2017).

- Smolen JS, Landewe RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:685-699

-

Wilsdon TD, Hill CL. Managing the drug treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Aust Prescr 2017;40:51-8.

- Hazlewood GS, Barnabe C, Tomlinson G, et al. Methotrexate monotherapy and methotrexate combination therapy with traditional and biologic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis: abridged Cochrane systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2016;353:i1777.

- Combe B, Landewe R, Daien CI, et al. 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:948-59.

- Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, Jr., et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1-26.

- Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:3-15.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2016;388:2023-38.

- Ledingham J, Snowden N, Ide Z. Diagnosis and early management of inflammatory arthritis. BMJ 2017;358:j3248.

- Bakker MF, Jacobs JW, Verstappen SM, et al. Tight control in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: efficacy and feasibility. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66 Suppl 3:iii56-60.

- Tay SH, Lim AY, Lee TL, et al. The value of referral letter information in predicting inflammatory arthritis--factors important for effective triaging. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33:409-13.

- Ong SP, Lim LT, Barnsley L, et al. General practitioners' referral letters--Do they meet the expectations of gastroenterologists and rheumatologists? Aust Fam Physician 2006;35:920-2.

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management of early rheumatoid arthritis. South Melbourne: RACGP, 2009 (accessed 12 January 2018).

- Harnden K, Pease C, Jackson A. Rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ 2016;352:i387.

- Arnold MH, Bleasel J, Haq I. Nocebo effects in practice: methotrexate myths and misconceptions. Med J Aust 2016;205:440-2.

- Rheumatology Expert Group. Therapeutic Guidelines: Principles of immunomodulatory drug use for rheumatological diseases in adults. West Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, 2017 (accessed 15 December 2017).

- Ngian GS, Briggs AM, Ackerman IN, et al. Management of pregnancy in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Med J Aust 2016;204:62-3.

- Flint J, Panchal S, Hurrell A, et al. BSR and BHPR guideline on prescribing drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding-Part I: standard and biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and corticosteroids. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55:1693-7.

- Australian Rheumatology Association. Notes on prescribing medications for rheumatic diseases in pregnancy. Sydney: ARA, 2017 (accessed 9 February 2018).

- Kavanaugh A, Cush JJ, Ahmed MS, et al. Proceedings from the American College of Rheumatology Reproductive Health Summit: the management of fertility, pregnancy, and lactation in women with autoimmune and systemic inflammatory diseases. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:313-25.

- Australian Rheumatology Association. Patient iInformation on Methotrexate. 2017 (accessed 1 February 2018).

- Claire Barrett. Personal communication, 18 February 2018.

- Australian Rheumatology Association. Notes for prescribers of low dose once weekly methotrexate (MTX). Sydney: ARA, 2017 (accessed 16 January 2018).

- Bianchi G, Caporali R, Todoerti M, et al. Methotrexate and rheumatoid arthritis: Current evidence regarding subcutaneous versus oral routes of administration. Adv Ther 2016;33:369-78.

- Bartlett SJ, Hewlett S, Bingham CO, 3rd, et al. Identifying core domains to assess flare in rheumatoid arthritis: an OMERACT international patient and provider combined Delphi consensus. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1855-60.

- Mouterde G, Baillet A, Gaujoux-Viala C, et al. Optimizing methotrexate therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Joint Bone Spine 2011;78:587-92.

- Visser K, van der Heijde D. Optimal dosage and route of administration of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1094-9.

- Jones G, Nash P, Hall S. Advances in rheumatoid arthritis. Med J Aust 2017;206:221-4.

- Australian Government Department of Human Services. Rheumatoid arthritis Initial PBS authority application form (PB109). 2017 (accessed 20 September 2017).