Stepping the appropriate path with GORD medicines

PPIs are among the most prescribed medicines in Australia. Guideline recommendations for GORD encourage starting daily PPI treatment for 4 to 8 weeks, and reducing or stopping treatment when GORD symptoms are well controlled.

GORD is a frequently managed condition

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, or GORD, is a commonly managed condition in primary care. In 2015–16, GORD accounted for 13.2% of all new problems managed in general practice in Australia, and was ranked eighth behind hypertension, upper respiratory tract infection, depression, diabetes, arthritis, back complaints and lipid disorders.1

People can be diagnosed with GORD if they have two or more reflux episodes per week, or if they have symptoms severe enough to significantly impair their quality of life.2

Heartburn – a symptom of GORD – is experienced by 15% to 20% of adults at least once each week.2,3

Download and print

PPIs are frequently prescribed medicines

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are among the most prescribed medicines in Australia.4

They are effective for the treatment of GORD, but are sometimes used inappropriately.2

Statistics from the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) for prescriptions in 2019–20 show:a,4

- two of the five available PPIs rank in the top five medicines by prescription volume

- three of the five available PPIs are among the top 30 medicines by prescription volumeb

- PPIs accounted for 10% of all top 30 medicines by prescription volume.

Data from the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) program illustrate the frequency of PPI use among general practice patients in Australia, and the conditions for which they were prescribed.5

From 1998–2017, BEACH collected data from approximately 1,000 randomly sampled GPs across Australia every year. The project has a database of over 1.7 million GP–patient encounters.6

Based on data acquired from 2,642 general practice patients enrolled in BEACH in 2015–16, 17.9% of patients were currently taking a PPI (14.2%) or had taken one in the past 12 months (3.7%).4 Within this subgroup, most were doing so for oesophageal reflux (67.9%).4

a Data are for prescriptions made under the PBS General Schedule (including doctor’s bag and under-copayment prescriptions).

b Among the top 50 medicines sorted by highest total prescription volume in 2019–20 (including doctor’s bag and under-copayment prescriptions), the PPIs rank: 3. pantoprazole, 4. esomeprazole, 25. rabeprazole, and 43. omeprazole. (Rosuvastatin and atorvastatin were ranked 1 and 2, respectively.)

Using PPIs for GORD wisely

The appropriate use of PPIs depends on:2

- only starting treatment with a PPI for 4 to 8 weeks with patients who have been diagnosed with GORD (according to the definition above)

- regularly reviewing patients who are taking PPIs for the treatment of GORD, with the aim of reducing or stopping PPI treatment if symptoms are well controlled.

These approaches align with Choosing Wisely Australia’s recommendations from the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) and the Gastroenterological Society of Australia (GESA) on the appropriate use of PPIs in clinical practice.7,8

- RACGP Choosing Wisely recommendation 1: Don’t use PPIs long term in patients with uncomplicated disease without regular attempts at reducing dose or ceasing.

- GESA Choosing Wisely recommendation 3: Do not continue prescribing long-term PPI medication to patients without attempting to reduce the medication down to the lowest effective dose or cease the therapy altogether.

There is evidence that approaches similar to these can reduce PPI use – from the initiative known as ‘Bye-Bye, PPI’.9

Is it GORD?

When a person presents with reflux symptoms, health professionals must distinguish between what is GORD and what is not GORD before prescribing a PPI.

As part of the patient assessment and diagnosis, possible causes of reflux and factors that can exacerbate it should be explored.2,3

People with GORD may experience typical reflux symptoms, such as heartburn, regurgitation or waterbrash (sudden and brisk stimulation of salivation).3 They may also experience atypical symptoms that are non-specific and not easily recognised as being due to reflux.3

These atypical symptoms may include chest pain, throat or voice changes, coughing, asthma, excessive belching, dyspepsia and nausea.3

The symptoms of GORD may be directly related to reflux episodes (such as heartburn and regurgitation) or due to complications of reflux disease (such as difficult or painful swallowing).3

For patients who have typical reflux symptoms and no alarm symptoms, response to a trial of PPI therapy can confirm the diagnosis of GORD.2

When is it gastro-oesophageal reflux, but not GORD?

Gastro-oesophageal reflux is a normal physiological event that usually occurs after eating, but GORD occurs when exposure of the oesophagus to the gastric contents becomes excessive.2,3

Symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux – in contrast to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease – are mild and intermittent, and do not significantly impair wellbeing or quality of life.2,3

If people have gastro-oesophageal reflux, their symptoms occur no more than once per week and are usually related to what they eat or drink.2

Are there any underlying causes of reflux symptoms?

Gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms are commonly induced by dietary triggers which may include high-fat meals, alcohol, coffee, chocolate, citrus fruit, tomato products, spicy foods, carbonated beverages and smoking.2,3

Some medicines may also cause or contribute to reflux symptoms, including:12,13

- aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- benzodiazepines

- bisphosphonates

- calcium channel blockers

- medicines with anticholinergic effects, such as tricyclic antidepressants

- nitrates.

Should GORD patients be tested for H pylori infection?

Symptoms of GORD can overlap with the gastrointestinal symptoms caused by Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) infection.2 The prevalence of H pylori infection is higher in people who are older, migrants, of lower socioeconomic status or institutionalised. The likelihood of H pylori infection is related most strongly to living conditions in childhood (when acquisition usually occurs).2

Patients with reflux-predominant symptoms are usually treated with acid-suppression therapy. Non-invasive testing and treating for H pylori (the ‘test-and-treat’ strategy) is a cost-effective strategy for younger adult patients (generally under 50 years, but younger if the patient is from a higher risk country) with dyspepsia and no red flags. Some guideline bodies recommend testing for H pylori before starting long-term PPI therapy for GORD.2

The usual choice of diagnostic test is the C13- or C14-urea breath test. The C13-urea breath test is not radioactive and is preferred for women of childbearing age. Before a breath test, antibiotic therapy should not be taken for at least 4 weeks, and PPI therapy should be withheld for at least 1 week (and preferably 2 weeks), to minimise the chance of false-negative results.2

The triple-therapy combining a PPI with amoxicillin and clarithromycin is the preferred first-line eradication treatment.2

Current Australian Therapeutic Guidelines for gastroenterology recommend H pylori eradication treatment in the following situations:2

- peptic ulcer disease (past or present)

- dyspepsia

- selected users of NSAIDs (including aspirin)

- atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia

- patients requiring long-term acid suppression

- close relatives of patients with gastric cancer

- patients already treated for early gastric cancer

- low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma

- patient preference to be treated (after possible harms and benefits have been discussed)

- gastric cancer prevention in communities with high incidence of gastric cancer.

If tested, eradication therapy should be offered to patients found to be infected with H pylori.2

Starting a PPI for GORD

Diet and lifestyle modifications may be all that is required for people with mild intermittent reflux symptoms, but people with GORD will also need initial treatment with a PPI.2

For the initial treatment of GORD, PPIs are generally recommended over H2 receptor antagonists because they are more effective at standard doses.2

A PPI is recommended at the standard dose (see Table 1), orally, once daily, 30 minutes to 1 hour before a meal.2

The initial course of PPI treatment should be for 4 to 8 weeks, following by a review. Treatment should be stepped down if symptom control is adequate after this initial course of treatment.2 Higher doses of PPIs are not indicated for initial PPI treatment for GORD, and are rarely needed in most cases of GORD.2

All PPIs are thought to have similar efficacy and adverse effects, although they may differ in their potential to cause drug interactions.14

Table 1. Dosage of PPIs approved for use in Australia2,14,15

| ||||||||||||||||||||

c. Esomeprazole 40 mg is not a standard dose. The lowest PBS-listed dose of esomeprazole is 20 mg; other low-dose preparations are appropriate step-down options for patients on esomeprazole 20 mg. |

When it is gastro-oesophageal reflux, but not GORD

On-demand medicines may be used if diet and lifestyle changes alone cannot sufficiently control mild intermittent gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms.2

In these situations, if as-required antacids (with or without alginates) do not provide adequate relief, then a PPI or an H2 receptor antagonist can be considered alongside continued diet and lifestyle changes.2

A PPI is recommended at the standard dose, orally, 30 minutes to 1 hour before a meal, once daily as required.2

Which lifestyle changes are effective?

Overall, lifestyle changes represent no risk to patients, may contribute to reduced reflux symptoms, and can lead to improved health in general. There is good evidence that weight reduction and smoking cessation are beneficial in reducing GORD.16,17

Stopping smoking

Data from epidemiological studies suggest that smoking is a risk factor for GORD.16

In the large population-based ‘HUNT’ study, stopping or reducing smoking led to an almost two-fold improvement in severe symptoms in people with normal BMI taking at least weekly antireflux medication, compared with those who continued to smoke.17

Losing weight

Australian GORD guidelines state that even modest weight loss can be effective for improving reflux symptoms in patients who are overweight.2

There is likely to be a dose-response relationship between increasing BMI and frequency of reflux symptoms.16,18-20

Changing diet

Anecdotal and experimental evidence varies about reflux symptoms and diet and alcohol use.16

Nonetheless, guidelines recommend that patients should try to identify and avoid their individual triggers while avoiding overly restricting their diet or persisting with measures that are not improving symptoms.2,3

Raising bedhead

If symptoms are worse at night or disrupt sleep, raising the head of the bed can reduce the number of reflux episodes, decrease reflux length and severity, or lead to faster acid clearance times.16,21,22

This can be achieved by placing 20 cm blocks under the head of the bed, or sleeping on a wedge pillow.16

Other changes

Reducing meal sizes, avoiding meals before bedtime, and avoiding vigorous exercise after eating may also help to reduce symptoms in some patients.2,16

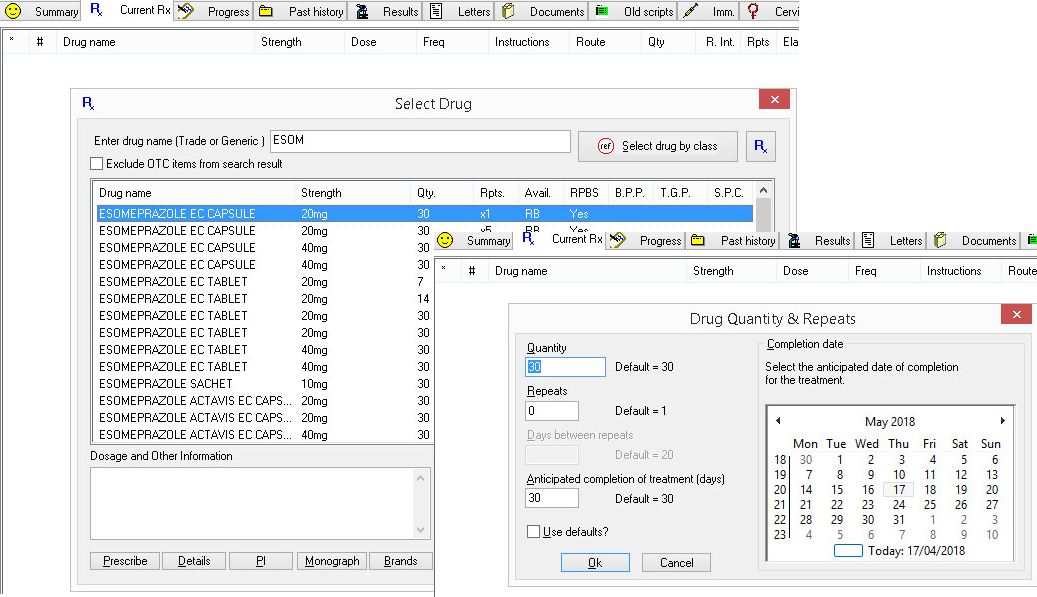

How many PPI script repeats should be prescribed?

Australian guidelines recommend that a patient with GORD should be initially treated with a PPI for 4 to 8 weeks, then undergo a review.2 This is equivalent to one or two prescription repeats.

In clinical information software, a GP can select a default to specify the duration of prescribed medication.

Alternatively, the GP can change the number of repeats for each individual prescription.

An illustration of how to do this in MedicalDirector is shown in Figure 1 below.

Stepping down a PPI for GORD

If symptoms are controlled after an initial 4–8-week trial of a PPI, guidelines recommend that treatment is titrated down to the lowest dose and frequency that controls symptoms, or stopped.2

There are different options for ‘stepping down’ PPIs, and the approach should be individualised in consultation with the patient.

Patients can step down PPI medicines by

- taking the standard dose less often (for example, alternate-day dosing)

- reducing their PPI dose to a low dose

- or only taking PPIs ‘on demand’ when they experience symptoms.2

A patient may move between the different step-down options, depending on their level of symptom control.

If symptoms are well controlled, an attempt can be made to step down treatment further, or to stop. If symptoms return, the patient should step back up to the PPI dose that provided adequate symptom control.

Clinical studies investigating strategies for PPI discontinuation have shown that PPIs can be discontinued without deteriorating symptom control in up to 64% of patients.24 However, in the BEACH study mentioned above, just 23% of patients taking a PPI had attempted to reduce their dose in the last 12 months, and only 15% had attempted to stop.5

What if reflux symptoms are still not controlled?

If reflux symptom control is inadequate with a daily PPI, especially after treatment at the standard dose for at least 8 weeks, guidelines recommend that health professionals check with patients that they are taking their PPI regularly, and at the optimal time (30-60 minutes before meals).2

If adherence to therapy is confirmed, endoscopy is indicated to exclude other conditions.

Treatment with a PPI at a high dose may be considered if endoscopy supports a diagnosis of GORD.

For high-dose PPI treatment, guidelines note that a standard PPI dose given twice daily is more effective than a double dose given once daily.2

However, if symptoms still do not respond to PPI treatment, patients should be referred to a specialist for further investigation.2

Help your patients help themselves

As part of the Starting, stepping down and stopping medicines program, NPS MedicineWise has also developed a consumer-tested Patient Action Plan.

Health professionals can print out the Patient Action Plan and use it with their patients to help explain the importance of using lifestyle changes together with PPIs to help manage symptoms.

Patients can identify their goals for stepping down and stopping their PPI medicines, and view a list of lifestyle changes that might help them manage their reflux symptoms.

References

- Britt H, Miller G, Henderson J, et al. General practice activity in Australia 2015–16. General practice series no. 40. Sydney: University of Sydney, 2016 (accessed 24 August 2021).

- Gastrointestinal Expert Group. Therapeutic Guidelines. Gastrointestinal, version 6. West Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, Dec 2019 (accessed 24 August 2021).

- Gastroenterological Society of Australia. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in adults. Clinical Update. Melbourne: GESA, 2011 (accessed 24 August 2021).

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Expenditure and prescriptions twelve months to 30 June 2020. Canberra: Department of Human Services, 2020 (accessed 24 August 2021).

- University of Sydney. SAND abstract No. 241 from the BEACH program: Proton pump inhibitor use among general practice patients. Sydney: University of Sydney, 2016 (accessed 24 August 2021).

- University of Sydney. Bettering the Evaluation and Care Of Health (BEACH). Sydney: University of Sydney, 2016 (accessed 24 August 2021).

- Choosing Wisely Australia. Gastroenterological Society of Australia: tests, treatments and procedures clinicians and consumers should question. 2016 (accessed 24 August 2021).

- Choosing Wisely Australia. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners: tests, treatments and procedures clinicians and consumers should question. 2016 (accessed 24 August 2021).

- Choosing Wisely Canada. Toolkit: Bye-Bye, PPI. 2017 (accessed 24 August 2021).

- Choosing Wisely Canada. Gastroenterology. Five things physicians and patients should question. 2017 (accessed 24 August 2021).

- Walsh K, Kwan D, Marr P, et al. Deprescribing in a family health team: a study of chronic proton pump inhibitor use. J Prim Health Care 2016;8:164-71.

- Australian Medicines Handbook. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Adelaide: AMH Pty Ltd, 2017 (accessed 24 August 2021).

- World Gastroenterology Organisation. Global perspective on gastroesophageal reflux disease. Milwaukee, USA: WGO, 2015 (accessed 24 August 2021).

- Australian Medicines Handbook. Gastrointestinal drugs. Adelaide: AMH Pty Ltd, 2017 (accessed 24 August 2021).

- National Institute of Clinical Excellence. Dyspepsia and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. London: NICE, 2014 (accessed 24 August 2021).

- Kang JH-E, Kang JY. Lifestyle measures in the management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: clinical and pathophysiological considerations. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2015;6:51-64.

- Ness-Jensen E, Lindam A, Lagergren J, et al. Tobacco smoking cessation and improved gastroesophageal reflux: A prospective population-based cohort study: The HUNT study. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:171-7.

- Jacobson BC, Somers SC, Fuchs CS, et al. Body-mass index and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in women. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2340-8.

- Hampel H, Abraham NS, El-Serag HB. Meta-analysis: Obesity and the risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:199-211.

- El-Serag HB, Graham DY, Satia JA, et al. Obesity is an independent risk factor for GERD symptoms and erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:1243-50.

- Khan BA, Sodhi JS, Zargar SA, et al. Effect of bed head elevation during sleep in symptomatic patients of nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:1078-82.

- Stanciu C, Bennett JR. Effects of posture on gastro-oesophageal reflux. Digestion 1977;15:104-9.

- Ahrens D, Behrens G, Himmel W, et al. Appropriateness of proton pump inhibitor recommendations at hospital discharge and continuation in primary care. Int J Clin Pract 2012;66:767-73.

- Haastrup P, Paulsen MS, Begtrup LM, et al. Strategies for discontinuation of proton pump inhibitors: a systematic review. Fam Pract 2014;31:625-30.