Low back pain is now the leading cause of disability worldwide,1 and one in seven Australians (13.6%) will suffer from back pain on any day.2

A recent Australian survey found that 67% of participants who presented to their GPs with low back pain reported that they were referred for diagnostic imaging.3

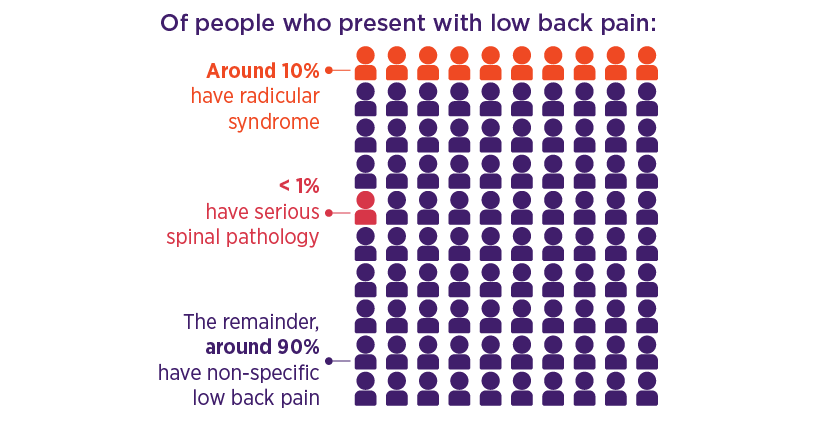

However, early diagnostic imaging of the back is not recommended unless there is clinical suspicion of a serious spinal pathology,4 which accounts for < 1% of all low back pain.2

The vast majority of acute cases are non-specific and self-limiting, resolving within a few weeks. Imaging does not change management for patients with acute non-specific low back pain and may lead to harm, such as fear-avoidance resulting from incidental findings, inappropriate treatment (such as surgery) and unnecessary radiation exposure.5

Imaging is frequently requested, however, to aid in diagnosis, rule out sinister pathology, guide treatment strategies for the clinician, and reassure the patient.6 Another significant driver is that patients commonly believe imaging is essential for assessing low back pain, and that X-rays are routine in the assessment of low back pain. Patients then expect GPs to refer them for X-rays. They have little awareness of the limited value of X-rays for diagnosing acute low back pain and often believe that there is no downside to their use.7,8

Apart from the issue of imaging, other elements of care for patients with acute non-specific low back pain could be improved by sticking more closely to guideline recommendations. These include:

- educate the patient

- provide assurance of a favourable prognosis, and

- encourage the patient to remain active and avoid bed rest.9

A diagnosis of exclusion

Non-specific low back pain is a diagnosis of exclusion.2,4,5,10

Choosing Wisely Australia supports a limited role for imaging

Through the Choosing Wisely initiative, five organisations recommend that doctors should not request imaging if there are no indicators of a serious cause for low back pain.

A biopsychosocial approach to management

Acute non-specific low back pain is self-limiting and resolves after 4–6 weeks for most patients.15 However, for the small number of patients who develop chronic disabling pain,5 the disease burden and cost of treatment can be substantial.16

In recent years, our understanding of the complexity of low back pain and the importance of a biopsychosocial approach, in preference to a purely biomedical approach, has increased significantly.

Guidelines recommend early treatment for patients with acute non-specific low back pain to address risk factors for poor prognosis (yellow flags). The aim is to prevent the development of chronic disabling pain.4,5,10

This can involve a risk stratification approach, where each patient’s risk level is assessed to help determine a specific management strategy.4

Example of tools to assess risk include the Subgroups for Targeted Treatment (STarT) Back, Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire4,5,10 or Predicting the Inception of Chronic Pain (PICKUP).17

First-line treatments

Patient education, reassurance and activity are first-line treatments for all patients with non-specific low back pain.5 NPS MedicineWise has developed a patient factsheet that explains the limited role of imaging and outlines other strategies for managing low back pain.

Encourage patients to stay as active as possible. This includes:5

- adopting normal movement and physical function

- continuing or returning to work.

Staying active, through pacing of activities, and resuming usual activities and work in a graded manner,5 helps to avoid:

- overdoing activity, which can cause pain exacerbations18

- underdoing activity;18 particularly prolonged bed rest, which can lead to muscle weakness, flexibility loss,19 possible increased low back pain recurrence risk.20

Encourage and collaborate with patients to identify things that make their pain worse, set goals for activity they wish to achieve and devise strategies to achieve them.21,22

NPS MedicineWise has developed a patient action plan, an individualised plan patients and doctors can develop together to set goals.

More information

Access our free accredited CPD activities on low back pain to find what is most suitable for you.

References

- Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 2018;391:2356-67.

- Bardin LD, King P, Maher CG. Diagnostic triage for low back pain: a practical approach for primary care. Med J Aust 2017;206:268-73.

- Carey M, Turon H, Goergen S, et al. Patients' experiences of the management of lower back pain in general practice: use of diagnostic imaging, medication and provision of self-management advice. Aust J Prim Health 2015;21:342-6.

- NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation. Management of people with acute low back pain: model of care. Chatswood: NSW Health, 2016 (accessed 1 March 2018).

- Rheumatology Expert Group. Therapeutic guidelines: Low back pain. West Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, 2017 (accessed 23 July 2018).

- Wheeler LP, Karran EL, Harvie DS.Low back pain: Can we mitigate the inadvertent psycho-behavioural harms of spinal imaging? Aust J Gen Pract. 2018;47(9):614-617.

- Hoffmann TC, Del Mar CB, Strong J, et al. Patients' expectations of acute low back pain management: implications for evidence uptake. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:7.

- Alzaher W, Belcher J, Granger R, et al. Low back pain. Sydney: NPS MedicineWise, 2017.

- Williams CM, Maher CG, Hancock MJ, et al. Low back pain and best practice care: A survey of general practice physicians. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:271-7.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. London, UK: NICE, 2016.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:478-91.

- Goergen S, Maher C, Leech M, et al. Acute low back pain. Education modules for appropriate imaging referrals. Sydney: Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists, 2015 (accessed 23 July 2018).

- Downie A, Williams CM, Henschke N, et al. Red flags to screen for malignancy and fracture in patients with low back pain: systematic review. BMJ 2013;347:f7095.

- Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, et al. Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:3072-80.

- Maher C, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet 2017;389:736-47.

- Machado GC, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, et al. Transient physical and psychosocial activities increase the risk of nonpersistent and persistent low back pain: a case-crossover study with 12 months follow-up. Spine J 2016;16:1445-52.

- Traeger AC, Henschke N, Hubscher M, et al. Estimating the risk of chronic pain: Development and validation of a prognostic model (PICKUP) for patients with acute low back pain. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002019.

- NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation. Pain and pacing. Sydney: NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation, 2018 (accessed 2 May 2018).

- North American Spine Society. Treating lower-back pain. How much bed rest is too much? Consumer Reports. Philadelphia, USA: Choosing Wisely, 2018 (accessed 2 May 2018).

- Belavy DL, Armbrecht G, Richardson CA, et al. Muscle atrophy and changes in spinal morphology: is the lumbar spine vulnerable after prolonged bed-rest? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:137-45.

- Gardner T, Refshauge K, McAuley J, et al. Patient-led goal setting: A pilot study investigating a promising approach for the management of chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:1405-13.

- Gardner T, Refshauge K, McAuley J, et al. Goal setting practice in chronic low back pain. What is current practice and is it affected by beliefs and attitudes? Physiother Theory Pract 2018:1-11.