After over-the-counter codeine: opportunities for better care

With low-dose codeine becoming prescription-only from 1 February 2018, health professionals and communities are preparing for the change. Find out more about how health professionals and communities are managing this transition.

Key points

- Extensive consultation and review of current data has concluded that the risks associated with low-dose codeine medicines outweigh their therapeutic benefit.

- From 1 February 2018, low-dose codeine will no longer be available over the counter in Australia – GPs, pharmacists and pain specialists will be at the forefront of managing this transition.

- This decision gives health professionals and patients opportunities to discuss alternative pain management options and explore more effective and safer approaches to pain.

- This decision will also bring to light patients with dependency issues requiring additional care and specialised management.

With low-dose codeine becoming prescription-only from 1 February 2018, health professionals and communities are preparing for the change. In most cases, pharmacists will be well-placed to suggest suitable alternative medicines or treatments. However, some patients will need their GPs to help manage the transition to more effective and safer pain management options, and support those who may have become dependent upon codeine. How should we work through this change, and what is the reasoning behind it? Here is some advice on transitioning to a post-OTC codeine world.

Download and print

The codeine rescheduling opportunity

From 1 February 2018, low-dose codeine (≤ 15 mga) will no longer be available over the counter (OTC).1,2 Indeed, some existing OTC codeine products may be delisted by the manufacturers, and may no longer be available in Australia.b The affected products include low-dose codeine in combination with paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain relief, and some preparations for the management of cold and flu symptoms. The decision to up-schedule all codeine products was made by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). An extensive risk–benefit analysis and consultation concluded that OTC medicines containing codeine have little additional analgesic benefit compared with similar medicines without codeine, but are associated with higher health risks.1,3

The change represents an opportunity for GPs and pharmacists to help people who have been using OTC codeine find alternative treatments that are effective and have a more favourable safety profile for each individual. For many people, it is a chance to have long-standing health issues addressed in a comprehensive and best-practice manner.

a Before 1 February 2018, preparations containing up to 15 mg of codeine were available over the counter.

b See the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods to check which products are still available.

OTC alternatives to codeine

Pharmacists can advise patients looking for short-term relief from cold or flu symptoms, or occasional mild-to-moderate acute pain, about suitable codeine-free medicines as well as appropriate non-pharmacological options.

A Choosing Wisely recommendation from the Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia states: ‘Don’t recommend the use of medicines with sub-therapeutic doses of codeine (< 30 mg for adults) for mild-to-moderate pain.’4 For more information on Choosing Wisely, see http://www.choosingwisely. org.au/home.

Australian guidelines recommend paracetamol or NSAIDs for the treatment of mild-to-moderate acute pain, alongside non-pharmacological options.5 Combined paracetamol and ibuprofen is an option that may offer better pain relief than either component alone.6 A meta-analysis study found the efficacy of the combination was roughly similar to the sum of the efficacies of the individual agents.7 The usual contraindications for NSAIDs should be observed.

A full assessment may be needed for acute pain that is not adequately controlled using OTC options, or for chronic pain.

A broader picture: treating recurrent acute orchronic pain

Patients who have been using low-dose codeine to treat recurring acute pain and chronic pain may decide to consult their GPs.

Treat severe and/or recurring acute pain, such as severe dysmenorrhoea, migraine and headache, according to best practice. Advise patients that OTC codeine products are no longer recognised as an appropriate, effective or safe way of treating these medical conditions. Diagnosis through history and appropriate clinical examination should be the basis of formulating a management plan in partnership with the patient.

Some recurring acute pain may be related to excessive use of codeine, such as codeine overuse headache.8 Classic symptoms of opioid withdrawal, such as nausea and diarrhoea, may be caused by codeine withdrawal in regular codeine users.9 It is important to reassure the patient that these symptoms are temporary and where they trouble the patient, they can be managed with medications.

Some patients who present to practices may have been using OTC codeine to manage chronic pain in the mistaken belief that codeine helps. However, codeine has no role, and other opioids only a limited role, in chronic pain.

This is an opportunity to provide reassurance and find strategies – including alternative medications where appropriate. The focus for managing chronic pain is functional improvement, as long-term pain relief is often an unrealistic goal.10

Dependence on codeine: dealing with theslippery slope

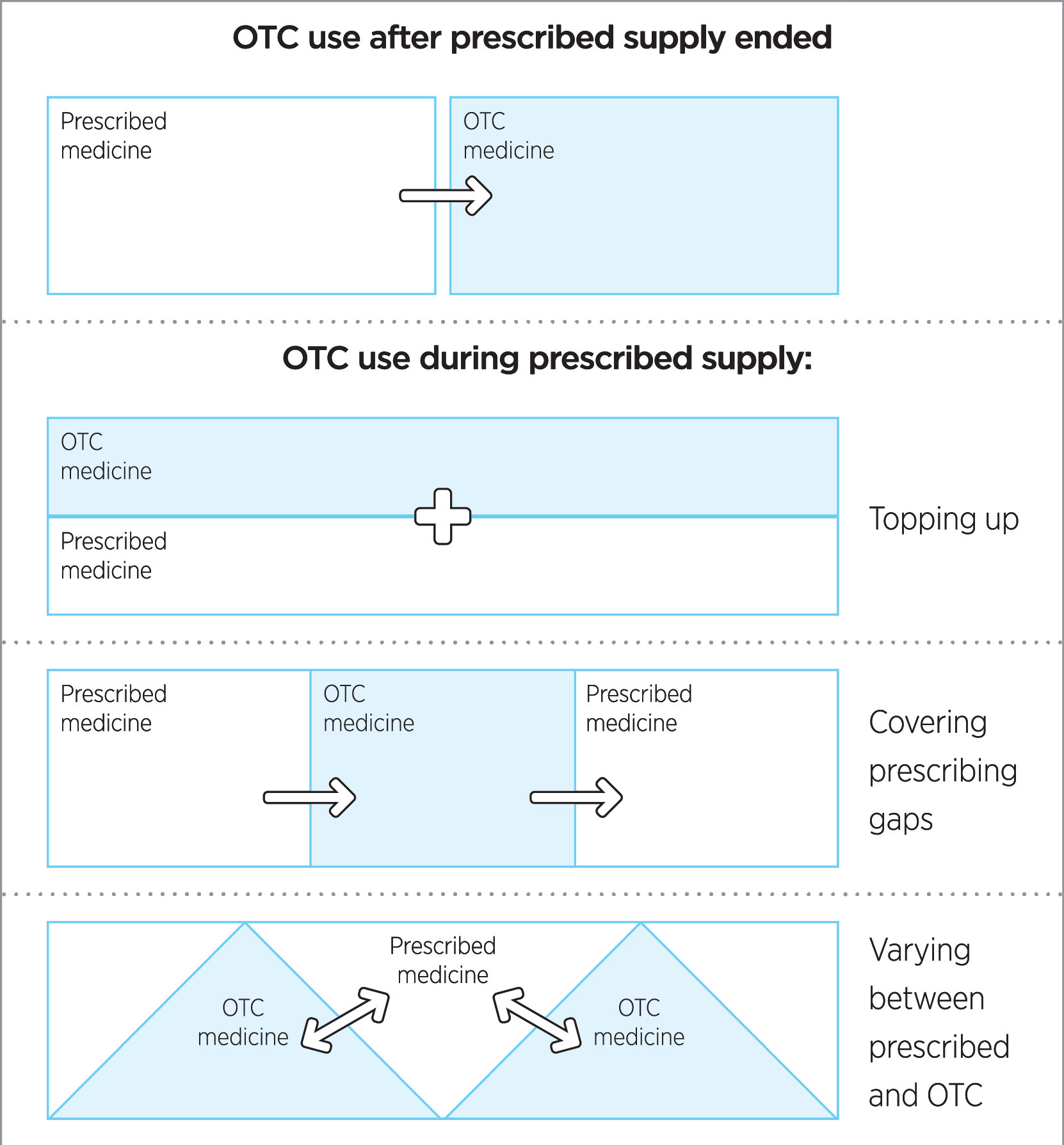

As well as self-medicating with OTC codeine, another pathway to OTC codeine use is via the initial use of higher strength prescription codeine products.8 A qualitative study of OTC codeine misusers found participants who were using both prescribed and OTC codeine medicines were relying on OTC medicines to cover gaps before a new prescription started, or using them to vary the medicine strength.11 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Relationship between over-the-counter medicine use and prescribed medicines. Adapted from Cooper RJ. BMJ Open 2013;3.11 (CC BY-NC 3.0)

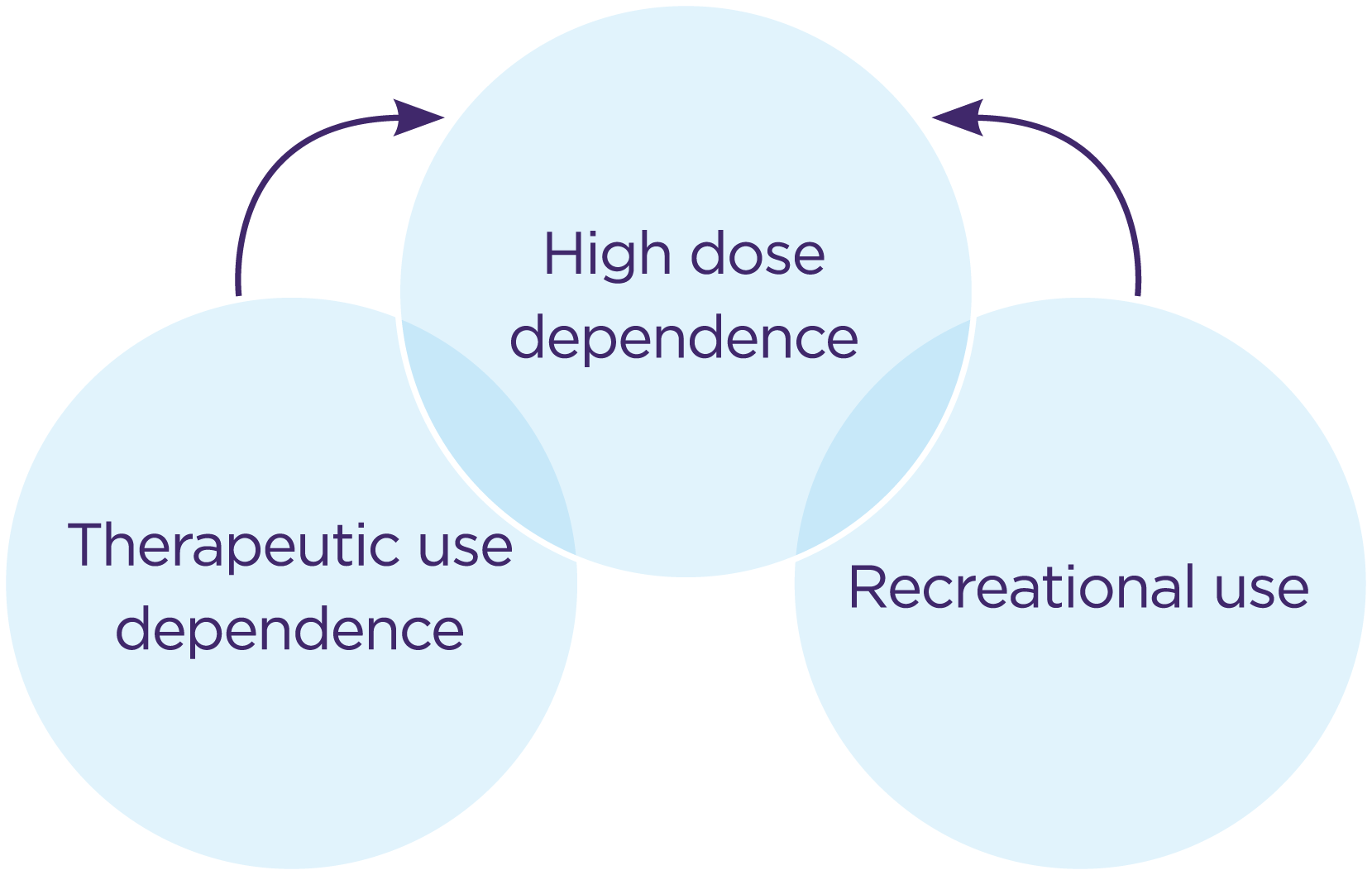

Although codeine is only a weak opioid,12 its misuse has resulted in dangerous and even deadly outcomes in Australia.13 An Australian study identified three types of codeine-dependent users:8

- Recreational users – using codeine for its euphoric effects

- Those with therapeutic dose dependence – characterised by self-control over maximum doses and limited awareness of dependency

- High-dose users – consuming substantial daily doses and at considerable risk due to concomitant paracetamol or ibuprofen consumption , as well as the impact of opioid dependence on their daily lives.

There is a grey area between therapeutic use of codeine and dependence, where people are medicating for opioid withdrawal while thinking they are treating their pain.8 Once dependent, people can also transition between dependence groups; moving from recreational or dependent use to become high-dose users.8 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Transition between dependence groups: adapted from Nielson S, Cameron J, Pahoki S. 20108 with permission from Turning Point and the authors.

‘I didn’t think I would get addicted to it – no,’ said one codeine user in an Australian study. ‘Obviously I realised later, but it’s quite insidious. It really does creep up on you.8

Many codeine-dependent people do not fit the stereotypical profile of a drug-dependent person. They may be employed in well regarded occupations and have no previous history of substance abuse.14 Drug seeking behaviour such as aggressively requesting a drug, often by name or brand name, and resisting alternative treatments can be a sign for possible codeine dependence.15

However, just because someone is asking for codeine does not mean they are dependent or that they are resistant to alternative options. Care should be taken to be non-judgemental, and each patient should be assessed on an individual basis.

The up-scheduling of codeine will result in some patients presenting with codeine dependence as well as possible pain or other ailments. This offers an opportunity to help these people with safer evidence-based care.

Codeine-dependent users: broaching thedifficult conversation

It can be difficult to address a patient’s possible misuse of codeine. Many resources exist on how to approach these difficult conversations. Discussions should be tailored to the individual’s health literacy.

- TGA tips for talking about codeine

- RACGP Practice policy: Approach to drug-seeking patients Appendix D8

A practice policy and a unified approach to drugs of dependence can help individual GPs respond safely and appropriately to requests for drugs of dependence.16,17

It is important to explore the reason why the patient is taking codeine, carrying out a full patient assessment if needed. If misuse is suspected, the RACGP suggests using a ‘matter of fact’ tone of voice while being empathetic to the individual’s circumstances. Getting upset, angry or being offended does not help with the rapport needed to facilitate appropriate care.

Stepping back from codeine

The RACGP recommends that if problematic codeine use has been identified, a doctor should offer remedial programs if this is within their skill set, or refer the patient to appropriate drug misuse agencies.16 What do such remedial programs look like? How should GPs help patients step back from codeine if it is needed?

For codeine-dependent users, detoxification, either medicated or unmedicated (‘cold turkey’), may not be the best option. An Australian study of codeine-dependent users found people generally relapsed after detoxification attempts.8

Pharmacotherapy or opioid replacement therapy (ORT) (using methadone or buprenorphine) are effective treatments for patients experiencing problematic use of prescription opioids or OTC codeine-containing analgesics.18

The National Opioid Pharmacotherapy Statistics report that on a snapshot day in 2013, 47,576 people were receiving pharmacotherapy for the treatment of opioid dependence.19 Of these people, 26,229 reported their primary opioid of concern, 1038 of whom reported codeine. An Australian study20 of codeine-seeking users found a large majority (up to 94%) reported using OTC codeine (possibly in addition to prescription codeine).

There are, however, substantial barriers for patients accepting these therapies due to the stigma against illicit opioid users. OTC codeine-dependent people may identify such treatments as being for ‘other people’, with terms like ‘bum’ and ‘junkie’ used.8 Despite these barriers, OTC misusers who have accessed the treatment have generally positive experiences. Online forums were also identified by these users as important for information and support.8

GPs can become approved prescribers of ORT and are well placed to provide holistic primary health care alongside treatment of the patient’s dependency.15 If confident, consider medicines that can help to alleviate symptoms of withdrawal such as anti-emetics for nausea or loperamide for diarrhoea. Coping strategies may also be beneficial to support withdrawal. These options may also be useful for patients waiting for expert assessment.

- Each of the States and Territories has its own regulatory requirements. Information on how to safely prescribe buprenorphine/naloxone and further information on ORT in Victoria.

- Australian Prescriber: Dealing with drug seeking behaviour. Includes links to state and territory legislative frameworks and clinical advisory services.

- DirectLine (1800 888 236, 24 hours, 7 days) can give information for the nearest prescriber and pharmacy that provides opioid replacement therapy services.

The evidence behind the TGA’s decision

The decision of the TGA to up-schedule low-dose codeine was a long, evidence-based and consultative process.1 The consultation started in April 2015, and included an extra deferral of the decision in November 2015 and an extra consultation period to assess further concerns. A detailed financial analysis was also carried out. But what is the evidence? There are many aspects.

Little incremental benefit of codeine

Medicines affected by the change are those combining low-dose codeine (≤ 15 mg) with paracetamol or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) such as ibuprofen, and/or an antihistamine or decongestant.2,13 Studies in acute pain suggest only a modest additional analgesic effectiveness when a high dose of codeine (60 mg) is added to paracetamol, but a higher rate of adverse effects after repeated doses.21-24

For low-dose codeine medicines affected by the decision, the evidence is mixed regarding the incremental benefit of codeine in such combinations, with the majority of studies showing no added benefit.13

Risks of the variable metabolism of codeine

Codeine delivers its analgesic effects when it is converted to morphine inside the body. Genetic differences lead to different rates of metabolism of codeine to morphine, and thus different responses to codeine. It is difficult, however, to predict the metabolism rate by studying the genotype alone.25 Between 75% and 92% of people metabolise codeine to morphine at a normal rate. At the low end of the spectrum, around 5% to 10% of people are poor metabolisers and receive little analgesic effect from codeine. Around 1% to 2% of people are ultra-rapid metabolisers who can convert codeine into large amounts of morphine.25,26 The ultra-rapid metabolisers should avoid codeine use due to the potential for toxicity.25

The ultra-rapid metaboliser phenotype has resulted in paediatric deaths26,27 and a neonatal death from morphine toxicity through breast milk,28 prompting safety warnings across the world.25,29-31

High human and financial costs

The addictive nature of codeine can result in people developing tolerance and escalating their dose. Such escalations can result in dangerous doses of the paracetamol or NSAIDs contained in codeine combination medicines.8 There is much documented evidence of the harm caused by OTC codeine in the Australian setting. Between 2000 and 2009 codeine related deaths increased from 3.5 to 8.7 deaths per million population, with a significant fraction of these patients recorded as also using OTC codeine.32

New research33 has assessed one aspect of the costs of OTC codeine misuse – those related to hospital admissions. The study used records from a 593-bed Australian public hospital taken over a 5-year period from June 2010 to June 2015. A total of 99 OTC codeine misuse admissions, involving 30 patients, were found. The estimated cost to the local healthcare system from OTC codeine misuse in this one hospital was $1,008,082, with a mean cost per hospital admission of $10,183.

People admitted to hospital had taken OTC codeine to help with a range of conditions, most commonly musculoskeletal pain (26.7%) and headache/migraine (13.3%). Some were consuming over six times (18 g) the daily recommended dose of ibuprofen, with others taking similarly excessive doses of paracetamol. Many had taken the medication over a prolonged period (up to 10 years for one patient).

Codeine misuse increasing despite earlier up-scheduling decision

The codeine misuse issue has been growing. A retrospective review27 of calls about codeine misuse made to the New South Wales Poison Information Centre (Australia’s largest poison centre) found the frequency of cases increased significantly from 2004 to 2015. The study examined 400 cases of codeine combination analgesic misuse in that period and found an average percentage increase of 19.5% for paracetamol/codeine and 17.9% for ibuprofen/codeine.

In 2010 the TGA up-scheduled codeine to ‘pharmacist only’ to address the risks, but there was no significant change in the upward trend of codeine misuse seen after this rescheduling.27

Onward and upward

The TGA decision is an opportunity to provide better care for patients who have been using OTC codeine. For some, it will be a simple switch - to an alternative, possibly more effective, treatment. For some, it will provide the stimulus to have their conditions diagnosed and treated effectively according to current best practice. Some will need support with codeine misuse behaviour as part of a move towards managing their conditions. Pharmacists, GPs and patients will all be part of this transition to a post-OTC codeine world.

Expert reviewers

Dr Richard Kidd

General Practitioner, Chair AMACGP and AMAQCGP

Clinical Lead Brisbane North PHN

Dr Adrian Reynolds

Clinical Associate Professor

President of the Chapter of Addiction Medicine, RACP

References

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Scheduling delegate’s final decision: codeine, December 2016. 2017 (accessed 10 October 2017).

- Tobin CL, Dobbin M, McAvoy B. Regulatory responses to over-the-counter codeine analgesic misuse in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. Aust N Z J Public Health 2013;37:483-8.

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Codeine information hub. 2017 (accessed 8 December 2017).

- Choosing Wisely. Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia: treatments pharmacists and consumers should question Sydney: Choosing Wisely Australia, 2017 (accessed 11 December 2017).

- Analgesic Expert Group. Therapeutic guidelines: Acute pain: a general approach. West Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd,, 2012 (accessed 23 October 2017).

- NPS Medicinewise. Paracetamol/ibuprofen combinations for acute pain. 2017 (accessed 10 October 2017).

- Moore RA, Derry CJ, Derry S, et al. A conservative method of testing whether combination analgesics produce additive or synergistic effects using evidence from acute pain and migraine. Eur J Pain 2012;16:585-91.

- Nielson S, Cameron J, Pahoki S. Over the counter codeine dependence: final report. 2010 (accessed 8 November 2017).

- Australian Medicines Handbook. Codeine. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd, 2017 (accessed 19 September 2017).

- Analgesic Expert Group. Therapeutic guidelines: Chronic pain: pharmacological management. West Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, 2012 (accessed 23 October 2017).

- Cooper RJ. ‘I can’t be an addict. I am.’ Over-the-counter medicine abuse: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2013;3.

- Iedema I. Cautions with codeine. Austr Prescr 2011;34:133-5.

- Shaheed CA MC, McLachlan A. Investigating the efficacy and safety of over-the-counter codeine containing combination analgesics for pain and codeine based antitussives. Canberra: Therapeutic Goods Administration, 2016 (accessed 12 September 2017).

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Submission to the Advisory Committee on Medicines Scheduling on proposed amendments to the Poisons Standard (Medicines) to delete the Schedule 3 entry for codeine, and reschedule the current Schedule 3 codeine entry to Schedule 4 due to potential issues of morbidity, toxicity and dependence. Canberra: Therapeutic Goods Administration, 2015 (accessed 7 December 2017).

- James J. Dealing with drug-seeking behaviour. Aust Prescr 2016;39:96-100.

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Prescribing drugs of dependence in general practice, Part A. East Melbourne: RACGP, 2015 (accessed 23 November 2018).

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Tips for talking about codeine: Guidance for health professionals with prescribing authority. 2017 (accessed 23 November 2017).

- Department of Health & Human Services. State Government of Victoria. Maintenance pharmacotherapy. Melbourne: Health.vic, 2016 (accessed 24 November 2017).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National opioid pharmacotherapy statistics 2013.Drug treatment series no. 23. Cat. no. HSE 147. Canberra: AIHW, 2014 (accessed 8 December 2017).

- Nielsen S, Murnion B, Dunlop A, et al. Comparing treatment-seeking codeine users and strong opioid users: Findings from a novel case series. Drug Alcohol Rev 2015;34:304-11.

- Murnion BP. Combination analgesics in adults. Australian Prescriber 2010;33.

- NPS Medicinewise. Analgesic options for pain relief. NPS News 47 2006.

- de Craen AJ, Di Giulio G, Lampe-Schoenmaeckers JE, et al. Analgesic efficacy and safety of paracetamol-codeine combinations versus paracetamol alone: a systematic review. BMJ 1996;313:321-5.

- Toms L, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Single dose oral paracetamol (acetaminophen) with codeine for postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009:CD001547.

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Codeine use in children and ultra-rapid metabolisers. 2015 (accessed 9 November 2017).

- Racoosin JA, Roberson DW, Pacanowski MA, et al. New evidence about an old drug-- risk with codeine after adenotonsillectomy. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2155-7.

- Cairns R, Brown JA, Buckley NA. The impact of codeine re-scheduling on misuse: a retrospective review of calls to Australia’s largest poisons centre. Addiction 2016;111:1848-53.

- Madadi P, Koren G, Cairns J, et al. Safety of codeine during breastfeeding: fatal morphine poisoning in the breastfed neonate of a mother prescribed codeine. Can Fam Physician 2007;53:33-5.

- European Medicines Agency. Codeine not to be used in children below 12 years for cough and cold. London: EMA 2015 (accessed 15 November 2017).

- Healthy Canadians. Health Canada’s review recommends codeine only be used in patients aged 12 and over. 2013 (accessed 15 November 2017).

- Food and Drug Administration. Safety review update of codeine use in children; new Boxed Warning and Contraindication on use after tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy. 2013 (accessed 15 November 2017).

- Roxburgh A, Hall WD, Burns L, et al. Trends and characteristics of accidental and intentional codeine overdose deaths in Australia. Med J Aust 2015;203:299.

- Mill D, Johnson JL, Cock V, et al. Counting the cost of over-the-counter codeine containing analgesic misuse: A retrospective review of hospital admissions over a 5 year period. Drug Alcohol Rev 2017.