What does thyroid testing in Australia look like?

Guidelines recommend thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) alone as the first step in investigating suspected hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism.4 Thyroid function tests (TFTs) – measuring TSH plus free tri‑iodothyronine (T3) and/or free thyroxine (T4) – are recommended only if TSH is abnormal or for investigation of certain conditions.4 The most common reasons for Australian general practitioners (GPs) to request thyroid function testing are hypothyroidism (13.4%) and hyperthyroidism (4.3%), weakness or tiredness (9.4%), and general check-ups (4.9%).5

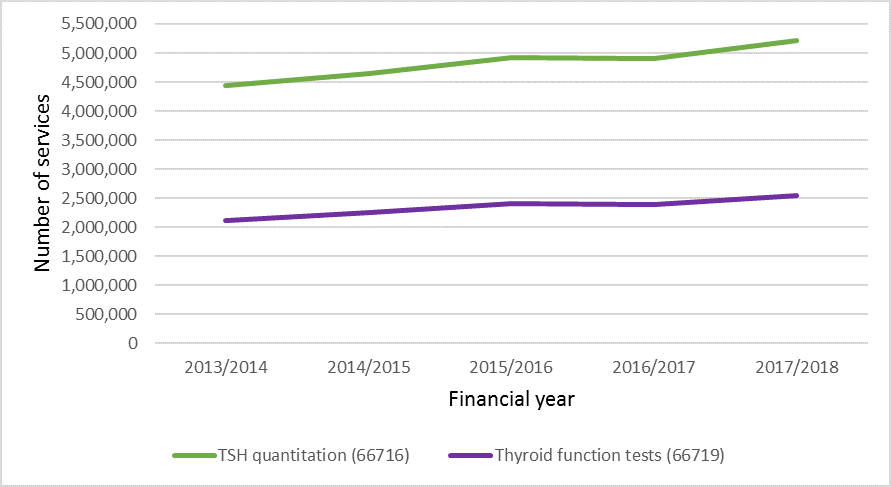

In 2017–18 there were 5.2 million TSH tests and 2.5 million TFT tests performed in Australia and these have been rising year on year (Figure 1).6 MBS data also indicates that 38% of Australians undergoing a TSH test had a repeat TSH test within 12 months.6

Figure 1: Trends in services for TSH quantitation and TFTS from July 2013 to June 2018 (MBS Statistics)

To image or not to image?

Choosing Wisely Australia recommends against routinely requesting ultrasound for patients with abnormal thyroid function tests if there is no palpable abnormality of the thyroid gland. The rate of neck ultrasound in Australia has increased four-fold between 1997 and 2017.7

MBS review taskforce recommendations

In 2017, The Government established the MBS Review Taskforce as an advisory body to review all 5,700 MBS items to ensure they are aligned with contemporary clinical evidence and practice as well as improve health outcomes for patients. The Pathology Clinical Committee and Diagnostic Imaging Clinical Committee have made the following recommendations in relation to thyroid tests and imaging:

- TSH should not be used as a screening test in asymptomatic patients, although some high-risk groups should have access to testing even when asymptomatic (pregnant women and those at elevated risk of thyroid disease).

- Repeat testing should not be conducted on patients within 12 months of a normal TSH without a change in their underlying thyroid condition or their thyroid hormone replacement treatment.

- Addition of appropriate (eg, evaluation of palpable thyroid nodule or neck mass) and inappropriate (eg, abnormalities in TFTs) indications to neck ultrasound MBS items.

Should I be screening my patients for thyroid disorders?

Despite non-specific symptoms, screening for thyroid disorder is not recommended in asymptomatic patients and TSH should not be used as a screening test.4 In some cases, where the patient presents with clinical symptoms or who are at high risk (eg, pregnant women, personal or family history of thyroid disease and autoimmune disease), case-finding is appropriate.4

Measure TSH as the first-line test in investigating thyroid disorders

When investigating suspected hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism in patients presenting with clinical symptoms or high-risk patients, measure TSH alone in the first instance.4 If TSH levels fall within the reference range then a primary thyroid disorder is unlikely and further TFTs are usually not necessary. TFTs are only recommended following abnormal TSH results or when investigating certain conditions (eg, pituitary disorder).4

How often should I order repeat TSH tests?

TSH levels are stable and unlikely to change over 12 months, so do not repeat TSH tests within 12 months of a normal result unless there is a clinical indication to do so.4 Use patient symptoms and other clinical indicators to guide the decision on when to repeat tests.4 Patients receiving thyroxine replacement therapy for hypothyroidism should have monitoring of TSH, usually 6–8 weeks following dose adjustment, with the aim of normalising TSH levels.4

When should I order a thyroid ultrasound?

Thyroid ultrasound is used to identify and characterise thyroid nodules, and is not part of the routine evaluation of abnormal thyroid function tests (over- or underactive thyroid function) unless the patient also has a palpably large goitre or a nodular thyroid.11

References

- Schneider C, Feller M, Bauer DC, et al. Initial evaluation of thyroid dysfunction - Are simultaneous TSH and fT4 tests necessary? PLoS One 2018;13:e0196631.

- O'Leary PC, Feddema PH, Michelangeli VP, et al. Investigations of thyroid hormones and antibodies based on a community health survey: the Busselton thyroid study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006;64:97-104.

- Britt H, Miller G, Henderson J, et al. General practice activity in Australia 2015-16. Sydney: FMRC, 2016 (accessed 15 December 2021).

- Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia. Position statement: Thyroid function testing for adult diagnosis and monitoring. NSW: RCPA, 2017 (accessed 15 December 2021).

- Bayram C, Valenti L, Britt H. Orders for thyroid function tests - changes over 10 years. Aust Fam Physician 2012;41:555.

- Medicare Benefits Schedule Review Taskforce. First report from the Pathology Clinical Committee – Endocrine Tests. 2017 (accessed 15 December 2021).

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The Third Australian Atlas of Healthcare Variation. Sydney ACSQHC, 2018 (accessed 15 December 2021).

- Bone and Metabolism Expert Group. Therapeutic Guidelines: Thyroid disorders. Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, 2019 (accessed 15 December 2021).

- Australian Thyroid Foundation. Hypothyroidism/Under active thyroid. Sydney Australia,, 2018 (accessed 15 December 2021).

- Australian Medicines Handbook. Drugs for thyroid disorders. Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd, 2021 (accessed 15 December 2021).

- Bahn Chair RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, et al. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Thyroid 2011;21:593-646.