Key points

- Use a targeted history and physical examination, and consider using a validated screening tool (eg DN4), to make a diagnosis of neuropathic pain and determine therapeutic approach.

- For neuropathic pain that is not adequately managed with non-pharmacological approaches, select a medicine on the basis of individual patient factors and medicine properties.

- Optimise the benefits of neuropathic pain medicines by starting with a low dose and titrating slowly before assessing response in relation to individual treatment goals.

- Recognise that medicines will often have limited effectiveness and that non-pharmacological strategies are a key component of a multidimensional management plan.

- Assess for potentially dangerous interactions and discuss with patients the risks associated with their medicines.

Practice Review – Revisiting pregabalin: Optimising safety in prescribing for neuropathic pain

Australian GPs recently received a Practice Review designed to assist with reflection on prescribing of pregabalin for neuropathic pain as well as prescribing in combination with opioids and benzodiazepines. It was developed in collaboration with GPs and has been sent to approximately 30,000 prescribers nationally, including all GPs.

- Access a sample report

- Read FAQs about the PBS Practice Review and how to interpret and understand your data

- Find national and RA aggregate data of prescribing patterns of GPs across Australia.

- Access a sample report

- Read FAQs about the PBS Practice Review and how to interpret and understand your data

- Find national and RA aggregate data of prescribing patterns of GPs across Australia.

Gabapentinoid misuse: a growing problem

Pregabalin and gabapentin (gabapentinoids), traditionally used to treat epilepsy, have increasingly been prescribed for pain. Now concerns are rising about potential misuse and abuse of these medicines.

Demonstration video: physical examination sensory tests

The diagnosis of neuropathic pain requires a targeted history and physical examination, which includes these 3 sensory tests:

- light touch test

- pinprick test

- dynamic mechanical allodynia test.

These tests may be performed for all neuropathic pain presentations (comparing painful areas to non-painful sites/areas).

Watch a demonstration video of the tests on the resources page

- light touch test

- pinprick test

- dynamic mechanical allodynia test.

RADAR: Pregabalin (Lyrica) for neuropathic pain

RADAR 4 April 2013

Pregabalin is an alternative treatment for people with neuropathic pain that has not responded to other drugs.

In my practice: Q&A

Q&A with Dr Ram Prasad, a Melbourne GP, answering questions on how he deals with diagnosis and prescribing for neuropathic pain.

For your patients

Demonstration videos of physical examination sensory tests

This video is a demonstration of 3 sensory tests – light touch, pinprick, and dynamic mechanical allodynia – on a patient with possible radicular back pain. These sensory tests may be performed for patients with all neuropathic pain presentations (comparing painful areas to non-painful sites/areas). They are easy to perform in general practice.

Viewing time: 6:05

These sensory tests are part of the DN4 (Douleur Neuropathique en 4 questions), a clinician administered validated assessment tool. The DN4 is simple and easy to perform in general practice.

- Light touch sensory test – start at 1:13 (viewing time: 0:43)

- Pinprick sensory test – start at 1:57 (viewing time: 1:15)

- Dynamic mechanical allodynia test – start at 3:13 (viewing time: 1:14)

Examiner: Dr Michael Vagg, Pain Specialist, Geelong, Victoria, Vice-Dean Elect, Faculty of Pain Medicine ANZCA, Clinical Senior Lecturer, Deakin University School of Medicine.

Practical tools and information

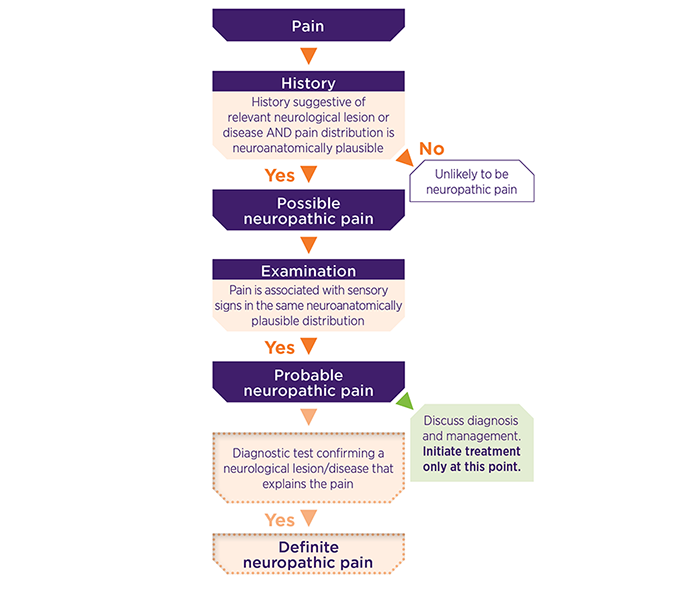

Grading system for neuropathic pain diagnosis

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) published the grading system in 2016. It addresses the difficulty of making an accurate diagnosis of neuropathic pain and allows appropriate treatment decisions in the face of uncertainty.

IASP define neuropathic pain as pain caused by a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory system. Neuropathic pain can be graded as possible, probable or definite based on evidence from history and clinical examination. Treatment can be commenced once probable neuropathic pain has been diagnosed, with further investigations only considered if these tests would inform treatment.

Neuropathic pain questionnaire – DN4

The DN4 (Douleur Neuropathique en 4 questions) is a clinician-administered assessment tool.

It consists of 10 items: 7 related to patient history and 3 to physical exam.

When all items are completed, it has good sensitivity and specificity. These items can be integrated into the diagnosis usually conducted by GPs in clinical practice.

Download a review copy of the DN4 [PDF]

Page 1 is the full version of the DN4, which includes questions about symptoms and involves conducting physical examination tests.

Page 2 is the DN4 interview, which only includes questions about symptoms.

Guidelines and reviews

Diagnosis and management

2020 Therapeutic Guidelines (TG) Pain and Analgesia Expert Group (subscribers only)

Guidelines cover comprehensive assessment and management of both acute and chronic pain.

Neuropathic pain is approached as an under-recognised component of acute pain, early assessment and management is recommended to help reduce the chances of this becoming chronic.

The principles of chronic pain management include addressing various sociopsychobiomedical factors simultaneously and prioritising active management strategies that improve social connection, use psychological techniques and increase physical activity.

Analgesics are not recommended as a first-line management strategy, and are not effective for all patients. TCAs (amitriptyline or nortriptyline), SNRIs (duloxetine or venlafaxine) and gabapentinoids (gabapentin or pregabalin) are considered as options for neuropathic pain where a trial of a medicine is appropriate. Where used, medicines should be part of a multidimensional management plan .

Diagnosis

Provides details of the IASP (International Association for the Study of Pain) principles behind patient history, physical examination and confirmatory tests, and details of how they are performed in clinical practice.

Provides clinical practice details for diagnosis, particularly patient history, physical examination and neuroanatomically plausible distribution.

Baron R, Binder A, Wasner G. Neuropathic pain: diagnosis, pathophysiological mechanisms, and treatment. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:807-19 (subscribers only)

Provides definitions of and what is done for a large number of sensory tests performed during a physical examination, and the expected pathological response for each one.

Haanpää ML, Backonja MM, Bennett MI, et al. Assessment of neuropathic pain in primary care. Am J Med 2009;122:S13-21 (subscribers only)

Provides clinical practice details for diagnosis, particularly for patient history and symptoms.

Pharmacological management

The guidelines are an update of the previous 2010 IASP guidelines.

It is a systematic review and meta-analysis of 229 randomised, double-blind studies of oral and topical pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain, including studies published in peer-reviewed journals since January, 1966, and unpublished trials.

Recommendations are based on the GRADE system.

For chronic neuropathic pain that is not adequately managed with non-pharmacological approaches, the 2020 Therapeutic Guidelines Pain and Analgesia1 recommend a TCA (amitriptyline or nortriptyline) or an SNRI (duloxetine or venlafaxine) or a gabapentinoid (pregabalin or gabapentin), with choice based on individual patient factors and medicine properties.

Lidocaine 5% patches are preferred for patients with localised neuropathic pain, particularly for older or frail patients and those on multiple medicines, because they have few systemic adverse effects and drug interactions.

Paracetamol and NSAIDs are not recommended for neuropathic pain.

Opioids have a limited role in the management of chronic noncancer pain and there is high-quality evidence that they provide little, if any, benefit for chronic noncancer pain and cause significant harms. For acute neuropathic pain, gabapentinoids may be preferred due to their faster onset of action, but their use may be limited by potential harms. A TCA or an SNRI are also recommended options.

Table 1: Pharmacological management

| Medicines | Study and notes |

|---|---|

| Amitriptyline and other tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) |

The IASP Guidelines, based on the 2015 Finnerup study2 (see also supplementary webappendix), made a strong GRADE recommendation for first-line use based on low NNT (for 30%-50% or at least moderate pain relief) and moderate quality of evidence, safety concerns for TCAs such as amitriptyline at dosages > 75 mg daily, low cost and large availability. NNT/NNH were 3.6/13.4. |

| Duloxetine and other SNRIs |

The IASP Guidelines, based on the 2015 Finnerup study2 (see also supplementary webappendix), made a strong GRADE recommendation for first-line use, and found that duloxetine and other SNRIs are positive in most clinical trials and have high quality of evidence, moderate effect size and moderate tolerability and safety. NNT/NNH were 6.4/11.8. The 2014 Lunn study4 on duloxetine for diabetic peripheral neuropathy came to similar conclusions as the 2015 Finnerup study, although fewer studies (4 versus 9) where included. The 2015 Gallagher study5 on venlafaxine for neuropathic pain in adults came to similar conclusions as the 2015 Finnerup study, but included a much smaller number of participants in the meta-analysis. |

| Gabapentin |

The IASP Guidelines, based on the 2015 Finnerup study2 (see also supplementary webappendix), made a strong GRADE recommendation for first-line use, and found that gabapentin was positive in most clinical trials and had high quality of evidence and moderate tolerability. NNT/NNH were 6.3/25.6. The 2017 Wiffen study6 on gabapentin focussed on specific causes; postherpetic neuralgia and painful diabetic neuropathy. For NNT the findings are supportive of the 2015 Finnerup study findings (NNT for postherpetic neuralgia was 6.7 and painful diabetic neuropathy 5.9; NNH for all conditions combined was 30). |

| Pregabalin |

The IASP Guidelines, based on the 2015 Finnerup study2 (see also supplementary webappendix), made a strong GRADE recommendation for first-line use, with high quality of evidence, and was positive in most clinical trials and had moderate tolerability. NNT/NNH were 7.7/13.9. The 2019 Derry study7 on pregabalin for neuropathic pain, with participant-reported pain assessment, found evidence for efficacy in postherpetic neuralgia, painful diabetic neuralgia and mixed/unclassified post-traumatic neuropathic pain. It found an absence of efficacy in HIV neuropathy and inadequate efficacy in central neuropathic pain. NNT for 50% pain intensity reduction for pregabalin (300 mg) for postherpetic neuralgia was 5.3, for painful diabetic neuropathy was 14, NNT were lower with pregabalin 600 mg. The authors concluded that 'some people will derive substantial benefit with pregabalin; more will have moderate benefit, but many will have no benefit or will discontinue treatment'. |

| Lidocaine (lignocaine) patches |

The IASP Guidelines, based on the 2015 Finnerup study2 (see also supplementary webappendix), made a weak GRADE recommendation for second-line use for peripheral neuropathic pain use based on poor quality of evidence, but high values and preferences, and excellent balance between desirable and undesirable side effects. NNT/NNH were not available. While the lack of high quality studies resulted in no pooling of data and meta-analysis was not performed, individual studies indicated some improvement compared to placebo. The 2014 Derry study8 on lidocaine for neuropathic pain in adults made similar conclusions to the 2015 Finnerup study. |

References

- Pain and Analgesia Expert Group. Therapeutic Guidelines: Pain and Analgesia. West Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd,

- Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:162-73.

- Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, et al. Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD008242.

- Lunn MP, Hughes RA, Wiffen PJ. Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy, chronic pain or fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD007115.

- Gallagher HC, Gallagher RM, Butler M, et al. Venlafaxine for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD011091.

- Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Bell RF, et al. Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:CD007938.

- Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA, et al. Topical lidocaine for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD010958.

- Derry S, Bell RF, Straube S, et al. Pregabalin for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;1:CD007076.