Key points

- On 1 January 2022, a new indication and clinical criteria were added to the Authority Required (Streamlined) PBS listing for dapagliflozin (Forxiga).

The new indication is symptomatic (NYHA class II–IV) heart failure and LVEF ≤ 40%. The treatment must be an add-on therapy to optimal standard treatment, which must include, unless contraindicated or cannot be tolerated, a beta blocker and ACE inhibitor or ARB or ARNI.

- Current Australian guidelines define HFrEF as LVEF < 50% and symptoms with or without signs of heart failure, and recommend that the standard treatment for HFrEF is a combination of an ACE inhibitor (or ARB), heart failure beta blocker and MRA, each up-titrated to the maximum tolerated or target dose.

The guidelines only recommend dapagliflozin and other SGLT2 inhibitors to reduce the risk of heart failure-related hospitalisation for people with CVD and type 2 diabetes with insufficient glycaemic control despite receiving metformin.

- Updated international guidance recommends an expanded role for dapagliflozin and other SGLT2 inhibitors for HFrEF with LVEF ≤ 40%.

SGLT2 inhibitors are included as standard treatment for HFrEF with LVEF ≤ 40% in combination with an ACE inhibitor (or ARB or ARNI), heart failure beta blocker and MRA.

- The clinical place of dapagliflozin in the treatment of HFrEF is for people who have persistent LVEF ≤ 40% despite receiving optimal standard treatment that may or may not include an MRA.

Changing the ACE inhibitor (or ARB) to an ARNI is another PBS-listed option for these patients. However, there is limited evidence to guide which option to select first and when to employ both options.

Abbreviations

|

HFrEF - heart failure with reduced ejection fraction HFpEF - heart failure with preserved ejection fraction LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction ACE - angiotensin-converting enzyme ARB - angiotensin receptor II blocker ARNI - angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor MRA - mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist SGLT2 - sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 NYHA - New York Heart Association TGA - Therapeutic Goods Administration PBS - Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme PBAC - Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee |

Classification of heart failure

An estimated 480,000 people in Australia have heart failure.1 Clinical diagnosis is made following a patient history, physical examination and investigations. An echocardiogram is recommended to confirm the diagnosis and classify heart failure. Classification helps guide management of the condition.2

Just under half of all people with heart failure can be classified as having reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).1 HFrEF (previously called systolic heart failure) is defined by the 2018 National Heart Foundation and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Guidelines for the Prevention, Detection, and Management of Heart Failure in Australia, as:2

- left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 50%, in the presence of symptoms with or without signs of heart failure, where the diagnosis is confirmed with an echocardiogram.

Over half of all people with heart failure can be classified as having preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).1 HFpEF (previously called diastolic heart failure) is defined as:2

- LVEF ≥ 50%, in the presence of symptoms with or without signs of heart failure and objective evidence of relevant structural heart disease and/or diastolic dysfunction without an alternative cause.

Type 2 diabetes is an independent risk factor for heart failure.2 Australian and overseas studies have found that for all people with heart failure, 10% to 47% also have type 2 diabetes.3,4

Evidence snapshot

What is known about this medicine?

Dapagliflozin is TGA-approved and PBS-listed for people with HFrEF who have LVEF ≤ 40%, with or without type 2 diabetes, as an adjunct to standard treatment.

When added to standard treatment for people with HFrEF who have LVEF ≤ 40%, dapagliflozin 10 mg daily reduced the risk of cardiovascular death or heart failure-related hospitalisation by 26%, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 21. In this patient group, the reductions in heart failure-related hospitalisation or cardiovascular death were similar regardless of whether they had type 2 diabetes.

Areas of uncertainty

The 2018 National Heart Foundation and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Guidelines for the Prevention, Detection, and Management of Heart Failure in Australia do not address the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in people who have HFrEF without type 2 diabetes.

There are no head-to-head trials comparing the PBS-listed options available for the treatment of people with HFrEF and persistent LVEF ≤ 40% despite receiving optimised standard treatment.

These options are changing the ACE inhibitor (or ARB) to an ARNI and/or adding dapagliflozin. There is limited evidence to guide which option to select first and when to employ both options.

What does NPS MedicineWise say?

The clinical place of dapagliflozin (and SGLT2 inhibitors more broadly) in the treatment for people who have HFrEF without type 2 diabetes continues to evolve.

People who have symptomatic HFrEF with LVEF < 50% are recommended to receive standard treatment with a combination of an ACE inhibitor (or ARB), heart failure beta blocker and MRA, each up-titrated to the maximum tolerated or target dose.

For people with HFrEF who have persistent LVEF ≤ 40% despite receiving optimal standard treatment that may or may not include an MRA, PBS-listed options now include changing the ACE inhibitor (or ARB) to an ARNI and/or adding dapagliflozin.

PBS listing

Authority Required (Streamlined)

On 1 January 2022, a new indication and clinical criteria were added to the General Schedule (Section 85) Authority Required (Streamlined) listing for dapagliflozin (Forxiga).5 It was previously listed only for type 2 diabetes.6

The new indication for dapagliflozin is chronic heart failure. The clinical criteria are the patient must:5

- be symptomatic with New York Heart Association (NYHA) classes II, III or IV, and

- have a documented LVEF ≤ 40%.

The treatment must be an add-on therapy to optimal standard chronic heart failure treatment, which must include, unless contraindicated according to the TGA-approved Product Information (PI) or cannot be tolerated, a:5

- beta-blocker and

- angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or

- angiotensin II antagonist (angiotensin II receptor blocker; ARB) or

- angiotensin receptor with neprilysin inhibitor (sacubitril/valsartan; ARNI).

The patient must not be receiving treatment with another medicine from the same class of medicines: sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors.5

May be prescribed by nurse practitioners (continuing therapy only)

Authorised nurse practitioners may only prescribe continuing therapy of this medicine after it has been initiated by a medical practitioner.5 See the PBS website for more information on nurse practitioner PBS prescribing.

What is it?

Dapagliflozin belongs to a class of medicines called SGLT2 inhibitors.7,8 It is TGA-registered and available on the PBS as an adjunct to standard treatment for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) with LVEF ≤ 40% as 10 mg tablets.5,8

Other medicines in this class include:

- empagliflozin and ertugliflozin (currently TGA-registered)8-10

- canagliflozin (previously TGA-registered).11

Mechanisms of action

SGLT2 is a protein primarily located in the proximal convoluted tubule of the nephrons in the kidneys.12,13 Inhibition of SGLT2 leads to multiple effects, including:12,14

- a glucose-lowering effect, which is well understood

- cardioprotective effects for heart failure that are not yet fully understood.

Glucose-lowering effect

SGLT2 is responsible for the resorption of approximately 90% of filtered glucose in the kidneys. This occurs through active transport driven by sodium co-transport across cell membranes. Inhibition of the SGLT2 protein activity increases urinary glucose excretion (glycosuria), leading to a glucose-lowering effect in the blood plasma.12,13

Type 2 diabetes is an independent risk factor for heart failure.2,15 Improving blood glucose control may help prevent the onset and progression of cardiovascular disease including heart failure. Several mechanisms may drive this reduction in risk including reduced ischaemia due to epicardial coronary artery disease and increased proinflammatory cytokines.15

Cardioprotective effects

Discovery of cardioprotective effects independent of the glucose-lowering effect

SGLT2 inhibitors were originally developed for their glucose-lowering effect for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. In response to concerns about an increased cardiovascular risk associated with several medicines that lower blood glucose (including sulfonylureas, muraglitazar and rosiglitazone), regulators in the USA in 2008 and Europe in 2012 mandated cardiovascular safety trials for all new glucose-lowering medicines, including SGLT2 inhibitors.12,16

While addressing safety concerns, these SGLT2 inhibitor trials also found improved cardiovascular outcomes (such as reduced hospitalisation for heart failure) among participants with type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, the outcomes were observed within months of the trials commencing.12

This suggested that the cardioprotective effects of SGLT2 inhibitors were independent of their glucose-lowering effect, as previous studies investigating the benefits of improved glycaemic control took several years to manifest a reduction in cardiovascular events.12,17

The cardiovascular safety trial findings led to HFrEF efficacy trials being conducted, including the 2019 Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction (DAPA-HF) trial with and without type 2 diabetes.12,18

See ‘What is the key study evidence?’ for more details about the 2019 DAPA-HF trial.

See ‘Additional evidence and guidance’ for more about the cardiovascular safety and HFrEF efficacy trials.

Proposed mechanisms

It is still not fully understood how SGLT2 inhibition may provide cardioprotective effects for people with heart failure independent of the glucose-lowering effect; however, there are a number of hypotheses.12,19

It has been suggested that sodium excretion and diuresis may improve left ventricular loading by reducing the preload volume. This action is also a feature of commonly used diuretics in the treatment of heart failure. However, SGLT2 inhibitors appear to achieve this without reducing the volume of blood as much as diuretics. Instead, they selectively target the cellular interstitial fluid, with no major impact on organ perfusion.12,19

There may also be a blood pressure-lowering effect through a reduction in arterial stiffness, improvement in vascular resistance and weight loss (the latter due to improved insulin sensitivity and glycaemic control).12,19

Novel mechanisms are also being investigated, such as benefits for cardiac remodelling due to reduced hypertrophy, fibrosis and inflammation, and a shift in cardiac metabolism to more oxygen-efficient sources of energy.12,19

Who is it for?

Heart failure

Dapagliflozin is TGA-approved for adults with symptomatic HFrEF as an ‘adjunct to standard of care therapy’. This indication was registered in November 2020.8

Other indications

Dapagliflozin is also indicated for adults with:8,20,21

- type 2 diabetes (October 2012)

- type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease (April 2020)

- proteinuric chronic kidney disease (September 2021).

Precautions

Dapagliflozin should not be prescribed:8

- for patients who have type 1 diabetes or severe hepatic impairment

- where its volume-depleting diuretic effect is a potential concern for the patient due to, for example, acute gastrointestinal illness

- for the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis

- three days prior to major surgery (maybe earlier for bariatric surgery).7

Initiating dapagliflozin is not recommended for patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 25 mL/min/1.73 m2.8

Where does it fit?

The clinical place of dapagliflozin (and SGLT2 inhibitors more broadly) in the treatment for people with HFrEF who do not have type 2 diabetes continues to evolve.22

There are differences between Australian guideline recommendations and international guidance, approved TGA indications and PBS listings for dapagliflozin, as well as between all three currently TGA-registered SGLT2 inhibitors.

Australian guidelines for HFrEF

Dapagliflozin and other SGLT2 inhibitors have a limited role in the pharmacological management of heart failure in the 2018 National Heart Foundation and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Guidelines for the Prevention, Detection, and Management of Heart Failure in Australia.2

Standard treatment for HFrEF

The guidelines define HFrEF as LVEF < 50% in the presence of symptoms with or without signs of heart failure, where the diagnosis is confirmed with an echocardiogram.2

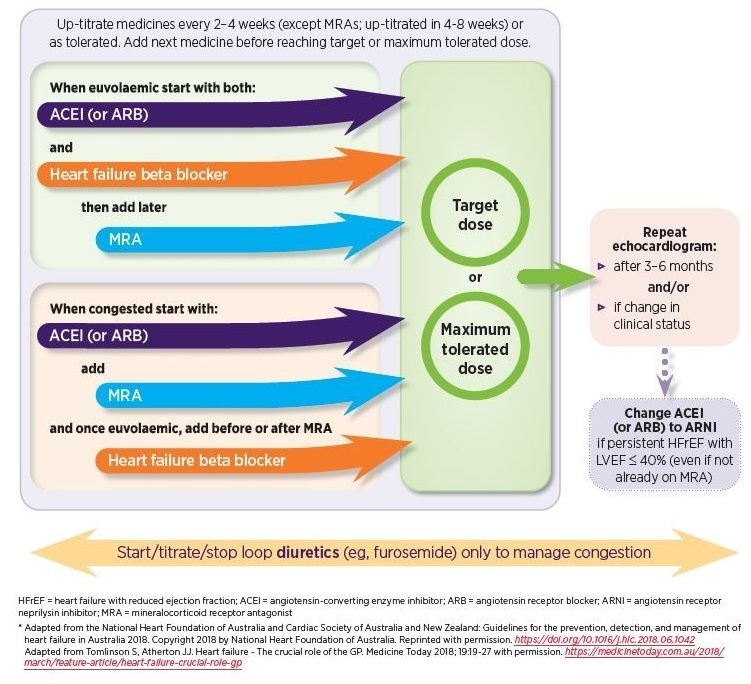

A combination of three medicines – an ACE inhibitor, heart failure beta-blocker and MRA – is recommended as standard treatment. Each medicine should be up-titrated to the maximum tolerated or target doses. If an ACE inhibitor is contraindicated or not tolerated, an ARB may be prescribed instead (see Figure 1).2

The combination of an ACE inhibitor, heart failure beta-blocker and MRA is much more effective than any individual medicine or combination of two of three medicines. It has been shown to improve prognosis in people with HFrEF, reducing all-cause mortality by 56% over 1–3 years when a medicine from each class is taken in combination at target doses.23

For people with HFrEF who have persistent LVEF ≤ 40%, despite receiving the maximum tolerated or target doses of an ACE inhibitor (or ARB) and heart failure beta blocker, with or without an MRA, an ARNI may be prescribed to replace the ACE inhibitor (or ARB).2

Figure 1: Initial pharmacological management for people with HFrEF2,24,25

Read an accessible version of this figure

For more details about the pharmacological management of HFrEF, see NPS MedicineWise News Up-titrating heart failure medicines: A practical guide.

There is evidence that prescribing Australian guideline-recommended medicines for HFrEF is an issue related to the quality use of medicines in primary care. In a 2021 study of over 20,000 Australian general practice patients with probable or definite heart failure, fewer than 4 of 10 were being prescribed the standard treatment for HFrEF – an ACE inhibitor (or ARB if not tolerated), heart failure beta-blocker and MRA, each one up-titrated to the maximum tolerated or target dose.26

Limited role for dapagliflozin and other SGLT2 inhibitors

The guidelines do not currently include a recommendation for dapagliflozin and other SGLT2 inhibitors for the management of patients with HFrEF who do not have type 2 diabetes.2

The role of dapagliflozin and other SGLT2 inhibitors to reduce the risk of heart failure-related hospitalisation is limited to patients with both cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes with insufficient glycaemic control despite receiving metformin.2

This reduction in heart failure-related hospitalisations was consistently demonstrated in the cardiovascular safety trials for SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes and either existing cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular risk factors.27-29 See ‘Additional relevant evidence and guidance’ for more details.

International guidance for HFrEF with LVEF ≤ 40%

The pharmacological management guidance for people with HFrEF who have LVEF ≤ 40% was updated in the USA, European and Canadian guidelines in 2021. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the United Kingdom also published guidance on dapagliflozin in the management of HFrEF with LVEF ≤ 40% in 2021.30-33

All of them included an expanded role for SGLT2 inhibitors, including dapagliflozin.30-33

They recommend that standard treatment for HFrEF with LVEF ≤ 40% include an SGLT2 inhibitor as a fourth medicine alongside the three existing recommended medicines – an ACE inhibitor (or ARB or ARNI), heart failure beta blocker and MRA – unless contraindicated.30-33

The USA, European and Canadian guidelines also consider an ARNI as a first-line treatment instead of an ACE inhibitor (or ARB).30-32

There is no clear consensus across these guidelines on whether to start an MRA prior to a SGLT2 inhibitor. However, they all agree that following diagnosis, standard treatment should be initiated promptly and doses adjusted every 2 weeks with the goal of optimising doses, as tolerated, within 3 to 6 months.30-32

TGA-approved indications and PBS listings

Table 1. TGA-approved indications for adults for SGLT2 inhibitors8-10

|

Dapagliflozin |

Empagliflozin |

Ertugliflozin |

|

|

Type 2 diabetes |

|||

|

Glycaemic control |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Established cardiovascular disease |

Yesc |

Yesd |

No |

|

Symptomatic HFrEF as an adjunct to standard of care therapye |

Yes |

Under evaluation by the TGA for the treatment of heart failure34 |

No |

|

Proteinuric chronic kidney disease |

Yesf |

No |

No |

a as an adjunct to diet and exercise, when metformin is not tolerated or contraindicated.

b other glucose-lowering therapies include metformin, sulfonylureas and dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 inhibitors; check relevant PI for clinical trials investigating SGLT2 inhibitors with other glucose-lowering therapies.

c or risk factors for cardiovascular disease, to reduce the risk of heart failure-related hospitalisation.

d to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death (in combination with other cardiovascular risk-reducing therapies).

e standard of care therapy in the 2019 DAPA-HF trial in the PI included most patients receiving an ACE inhibitor (or ARB or ARNI), heart failure beta blocker, MRA and diuretic.

f Stage 2, 3 or 4 chronic kidney disease (and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥ 30 mg/g) to reduce the risk of progressive decline in kidney function.

Table 2. PBS listings for SGLT2 inhibitors5,6,35

|

Dapagliflozin |

Empagliflozin |

Ertugliflozin |

|

|

Type 2 diabetesg |

|||

|

Monotherapy |

No |

No |

No |

|

Dual therapy in combination with metformin or a sulfonylurea |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Triple therapy in combination with: |

|||

|

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

In combination with insulin |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue |

No |

No |

No |

|

Chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF)h |

Yes |

Recommended at the PBAC Meeting November 2021; PBS listing date to be determined. |

No |

|

Chronic kidney disease |

No |

No |

No |

g Patient must have, or have had, a HbA1c measurement > 7% despite treatment. See PBS website for further details.

h Patient must have symptomatic (NYHA class II–IV) HFrEF with documented LVEF ≤ 40% and treatment must be add-on therapy to optimal standard chronic heart failure treatment, which must include, unless contraindicated or not tolerated, a beta blocker and ACE inhibitor or ARB or ARNI.

Clinical place of dapagliflozin in the treatment of HFrEF with LVEF ≤ 40%

For people with HFrEF who have persistent LVEF ≤ 40% despite receiving optimal standard treatment that may or may not include an MRA, there are now two PBS-listed options:5,6

- changing the ACE inhibitor (or ARB) to an ARNI, or

- adding dapagliflozin.

People already taking an ARNI may also have dapagliflozin added to their treatment. If a patient first has dapagliflozin added to standard treatment, the ACEI (or ARB) may also then be changed to an ARNI at a later date.5,6

However, there are no head-to-head trials for people with HFrEF who have persistent LVEF ≤ 40% comparing the two PBS-listed options for treatment described above, and there is limited evidence providing guidance regarding which should be selected first.

Dapagliflozin may be appropriate in some people when an ARNI may not be prescribed, eg, people with hyperkalaemia (serum potassium > 5.5 mmol/L) or a history of ACE inhibitor- or ARB-associated angioedema.2,25

Alternatively, an ARNI may be appropriate in some people when dapagliflozin should not be prescribed, eg, people with comorbid type 1 diabetes or severe hepatic impairment.8,36 See ‘Who is it for?’ for more details on precautions.

Most participants in the 2019 DAPA-HF trial (see below) were taking standard treatment prior to randomisation, including 71% who were taking an MRA and 10% an ARNI.18

A 2020 meta-analysis of the 2019 DAPA-HF trial and 2020 EMPEROR-Reduced trial (a HFrEF efficacy trial for empagliflozin) and their sub-groups showed that the baseline use of ARNI did not influence the treatment effect of the SGLT2 inhibitor.2

A 2021 network meta-analysis of six ARNI and SGLT2 inhibitor HFrEF efficacy trials concluded that the combination of an ARNI and SGLT2 inhibitor (added to other standard treatments including a beta blocker, MRA and diuretic) provides better cardioprotective effects than that provided by either class alone.27-29

What is the key study evidence?

2019 DAPA-HF trial

The reductions in heart failure-related hospitalisations for people taking SGLT2 inhibitors found in the cardiovascular safety trials of type 2 diabetes led to HFrEF efficacy trials in people with and without type 2 diabetes.18,37

The 2019 DAPA-HF trial was the first of these. It enrolled people with symptomatic (NYHA class II–IV) HFrEF and LVEF ≤ 40% (mean LVEF 31.1%). At baseline, 41.8% of the 4,744 participants had type 2 diabetes, and the baseline use of standard treatments for HFrEF was high: 93.6% were taking an angiotensin inhibitor (56.1% ACE inhibitor, 27.6% ARB, 10.7% ARNI), 96.1% a beta blocker, 71% an MRA and 93.4% a diuretic.18,38

The primary composite outcome was worsening of heart failure (hospitalisation or an urgent visit for heart failure) or cardiovascular death. This outcome was reduced by 26% with dapagliflozin in comparison to placebo (16.3% with dapagliflozin vs 21.2% with placebo). This corresponds to a NNT of 21 (95% confidence interval [CI] 15 to 38) to prevent one event (worsened heart failure or cardiovascular death).18

Sub-group analyses showed that the treatment effect was maintained in patients with and without type 2 diabetes and those receiving or not receiving concomitant MRA at baseline.18 Dapagliflozin was the most effective for patients with NYHA class II heart failure (those with mild symptoms and slight limitations during ordinary physical activity).18,37

Reason for PBS listing

At the PBAC September 2021 Intracycle Meeting, a change to the PBS listing was recommended for dapagliflozin to include chronic heart failure as a new indication.39

Based on the 2019 DAPA-HF trial, the key study in the listing submission, the PBAC found with a high level of certainty that dapagliflozin added to standard treatment had a moderate benefit and non-inferior safety, compared with standard chronic heart failure treatment alone for people with HFrEF who have LVEF ≤ 40%.22

The PBAC noted the treatment effect appeared to be consistent both for people with and without type 2 diabetes.22,40

The PBAC considered the evidence using the definition of HFrEF as people with symptoms with or without signs of heart failure and LVEF ≤ 40%. Standard treatment was defined as a beta blocker and ACE inhibitor or ARB or ARNI. The PBAC recognised that MRAs and other background heart failure therapies could be considered as part of standard of care for some patients if appropriate. However, given the variability in individualised care, these were not included in the main evaluation considered by the PBAC.22

Given that dapagliflozin has a different mechanism of action to that of ARNIs, the PBAC advised that patients potentially would switch from, add on or displace ARNIs. The PBAC also recognised that SGLT2 inhibitors are gaining increasing prominence in international guidelines for heart failure.22

Dosing issues

The recommended dose of dapagliflozin is a 10 mg tablet taken orally once daily at any time of the day, regardless of meals.8

Unlike other medicines for heart failure, dapagliflozin does not have a starting dose, with up-titration to the maximum tolerated dose or target dose.32

No adjustments are required for people with renal impairment; for older people; or on the basis of weight, sex or race.8

The glucose-lowering efficacy of dapagliflozin is dependent on renal function and is reduced when the eGFR is < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2. For patients who have type 2 diabetes, additional glucose-lowering treatment should be considered.8

Safety issues

For information about reporting adverse reactions to the TGA, or to report suspected adverse reactions online, see the TGA website.

Dehydration (volume depletion)

For patients who are dehydrated (volume depleted) or taking loop diuretics, assess the volume status and correct any volume depletion if required before and after starting treatment; for example, consider reducing the diuretic dose.7

For patients with a condition that may lead to dehydration, such as heat stress or severe infection, careful monitoring of the volume status and temporary cessation of dapagliflozin is recommended.8

Renal impairment

Dapagliflozin increases serum creatinine and decreases the eGFR. Renal function abnormalities can occur after initiating dapagliflozin. Patients who are dehydrated (volume depleted) may be more susceptible to these changes.8

Check the patient’s renal function before starting treatment and then periodically as clinically indicated (at least annually). Serum creatinine may increase after starting treatment, but this is usually transient.7 A reduction in the eGFR of up to 15% may occur but is also usually transient and generally resolves within 1–3 months.31

Hypotension

Caution is required when taking dapagliflozin for patients with hypotension if the volume-depleting diuretic effect causes a drop in blood pressure that poses a risk, such as for patients taking blood pressure-lowering medicines, those with known cardiovascular disease and those who are older.8

Hypoglycaemia

Hypoglycaemia is generally a common adverse effect (> 1.0%) for people taking dapagliflozin; however, the frequency may be lower depending on other medicines being taken.7,8 For example, hypoglycaemia is rare when taking SGLT2 inhibitors in the absence of concomitant insulin and/or secretagogue therapy (eg, sulfonylurea). Background glucose lowering therapy might need to be adjusted to prevent hypoglycaemia.31

Genitourinary infections

Urinary glucose excretion may be associated with an increased risk of urinary tract infection (UTI). Temporary cessation of dapagliflozin should be considered when treating patients with pyelonephritis or urosepsis. Stopping dapagliflozin may be considered in cases of recurrent UTIs.8

Genital infections (eg, vulvovaginal candidiasis, balanitis) are common (> 1.0%), more frequent in women than men, generally mild to moderate, and mostly respond well to standard treatment and do not require cessation of treatment.7,8

Perineal necrotising fasciitis (Fournier’s gangrene) is a rare (< 0.1%) but serious and potentially life-threatening infection that has been reported in female and male patients with type 2 diabetes treated with dapagliflozin. Patients presenting with pain or tenderness, erythema and/or swelling in the genital or perineal area, fever, or malaise should be evaluated for perineal necrotising fasciitis. If suspected, dapagliflozin should be stopped and treatment provided.7,8

Ketoacidosis

Ketoacidosis is a rare (< 0.1%) but severe adverse effect of dapagliflozin. Cases of hospitalisation and mortality due to ketoacidosis have been reported in patients taking dapagliflozin. Consider withholding dapagliflozin if there is a risk of ketoacidosis such as in patients with acute serious illness, prolonged fasting, bowel preparation, low carbohydrate intake or excessive alcohol intake.7

Patients presenting with symptoms (including nausea, unexplained severe vomiting, abdominal pain, malaise and shortness of breath) or high anion gap metabolic acidosis should be assessed, even if blood glucose levels are normal or mildly raised (< 14 mmol/L [250 mg/dL]). If ketoacidosis is suspected, dapagliflozin should be ceased, the patient should be evaluated, possibly including blood ketones testing, and prompt treatment should be initiated. Report to the TGA if a causal relationship with the medicine is suspected.7,8

Surgery

Cessation of dapagliflozin is recommended three days prior to major surgery due to perioperative risks such as dehydration, UTI and renal impairment and the potential increased risk of ketoacidosis (the latter risk may remain high for weeks or months after surgery). For bariatric and other surgeries, cessation may be needed earlier. Seek specialist advice for guidance.7

Fractures and amputations

The evidence on whether there is an increased risk of fractures is mixed, and more evidence is required to understand the association with dapagliflozin and other SGLT2 inhibitors as a class effect. For patients with type 2 diabetes, it is important to regularly examine the feet and counsel all patients on routine preventative footcare.7,8,14

Information for patients

Prescribers and pharmacists are encouraged to discuss the following with patients and carers:7,41

- Dapagliflozin may cause dizziness in some people. Low blood sugar levels may also slow reaction times and affect the ability to drive or operate machinery.

- Do not drive a car, operate machinery or perform other activities that have a high chance of injury if feeling dizzy or lightheaded.

- Urine will test positive for glucose while taking dapagliflozin.

- Make sure to drink enough water to control thirst and avoid dehydration.

- Taking dapagliflozin can increase the chances of genital infection (eg, thrush). To reduce the chance of infection, it is important to maintain good hygiene and be aware of the signs and symptoms of infection. Seek medical help if infection occurs (eg, if there is fever and pain, tenderness or swelling in the genital area).

- Dapagliflozin can be taken with or without food.

Additional evidence and guidance

MRAs

The PBS listing for dapagliflozin in HFrEF with LVEF ≤ 40% requires that the treatment must be an add-on therapy to optimal standard treatment, which must include, unless contraindicated or cannot be tolerated, a beta blocker and ACE inhibitor or ARB or ARNI, and allows for treatment with or without an MRA.5

A 2017 network meta-analysis of 57 trials of HFrEF found that when compared with placebo, the dual combination of an ACE inhibitor with a heart failure beta blocker reduced the risk of mortality over 1 to 3 years by 43%, whereas the combination of an ACE inhibitor, heart failure beta blocker and MRA reduced the risk by 56%.23

Over 70% of participants in the 2019 DAPA-HF trial were taking an MRA at baseline, and sub-group analysis showed a similar treatment effect with or without MRA.18

Spironolactone is the most commonly prescribed MRA in Australia.26 It is unrestricted on the PBS. It is the lowest cost option for most patients when supplied via a PBS-subsidised prescription as an add-on to an ACE inhibitor (or ARB) and heart failure beta blocker for HFrEF.6 Adverse effects such as hyperkalaemia, renal impairment, hypotension, or gynaecomastia can limit its use in some patients.2

The PBS listing for eplerenone is Authority Required (Streamlined). Its use is restricted to people who have HFrEF with LVEF ≤ 40% where the condition occurs within 3 to 14 days following an acute myocardial infarction and treatment is commenced within 14 days of an acute myocardial infarction.6

ARNIs

The PBS listing for dapagliflozin in HFrEF with LVEF ≤ 40% requires that the treatment must be an add-on therapy to optimal standard treatment, which must include, unless contraindicated or cannot be tolerated, a beta blocker and ACE inhibitor or ARB or ARNI, and allows for treatment with or without an MRA.5 Sacubitril/valsartan is the only TGA-approved and PBS-listed ARNI.6

In recent years, switching from an ACE inhibitor (or ARB) to an ARNI has become the main treatment option in the 2018 National Heart Foundation and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Guidelines for the Prevention, Detection, and Management of Heart Failure in Australia for patients who have HFrEF with persistent LVEF ≤ 40%, despite receiving the maximum tolerated or target doses of an ACE inhibitor (or ARB) and heart failure beta blocker, with or without an MRA.2 Dapagliflozin is an additional PBS-listed treatment option for these patients.5

The same 2017 network meta-analysis of 57 trials of HFrEF described above found that when compared with placebo, the combination of an ACE inhibitor, heart failure beta blocker and MRA reduced the risk of mortality over 1 to 3 years by 56%, whereas the combination of an ARNI, heart failure beta blocker and MRA reduced the risk by 63%.23

As mentioned above, there is limited evidence providing guidance on which treatment - an ACE inhibitor (or ARB) to an ARNI or adding dapagliflozin - should be selected first.

However, a 2021 network meta-analysis of six ARNIs and SGLT2 inhibitor HFrEF trials found that similar cardiovascular benefits were observed when either an ARNI or SGLT2 inhibitor were added to other standard treatments.42

Similar cardiovascular benefits were seen with both classes in people with and without diabetes, and better cardiovascular outcomes were reported when both ARNIs and SGLT2 inhibitors were used concomitantly.42

Dapagliflozin and other SGLT2 inhibitors

SGLT2 inhibitor cardiovascular safety trials

The cardiovascular safety trials were published for dapagliflozin and other SGLT2 inhibitors between 2015 and 2020. Despite differences in their study populations that might explain why some trials did not demonstrate significant reductions in the primary composite outcome or mortality, these trials consistently showed a 27% to 35% reduction in heart failure-related hospitalisations as a secondary outcome (see Table 3).27-29,43

Table 3: SGLT2 inhibitor cardiovascular safety trials in patients with type 2 diabetes27-29,

|

Trial |

EMPA-REG 2015 |

CANVAS 2017 |

DECLARE-TIMI 58 2019 |

VERTIS-CV 2020 |

|

Population |

Type 2 diabetes + established CVD (100%) |

Type 2 diabetes + established CVD (65.6%) or ≥ 2 CVD risk factors (34.4%) |

Type 2 diabetes + established CVD (40.6%) or ≥ 2 CVD risk factors (59.4%) |

Type 2 diabetes + established CVD (100%) |

|

SGLT2 inhibitor vs placebo |

Empagliflozin 10 mg or 25 mg once daily |

Canagliflozin 100 mg to 300 mg once daily |

Dapagliflozin 10 mg once daily |

Ertugliflozin 5 mg or 15 mg once daily |

|

Primary outcome |

Cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction or non-fatal stroke |

|||

|

Hazard ratio (95% CI) p-valuei,j |

0.86 (0.74–0.99) < 0.001i, 0.04j |

0.86 (0.75–0.97) < 0.001i, 0.02j |

0.93 (0.84–1.03) < 0.001i, 0.17 (n.s.)j |

0.97 (0.85–1.11)k < 0.001i, N/A (n.s.)j |

|

Secondary outcomes |

||||

|

Death (any cause) Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

0.68 (0.57–0.82) p < 0.001 |

0.87 (0.74–1.01) n.s. |

0.93 (0.82–1.04) n.s. |

0.93 (0.80–1.08) n.s. |

|

Cardiovascular death Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

0.62 (0.49–0.77) p < 0.001 |

0.87 (0.72–1.06) n.s. |

0.98 (0.82–1.17) n.s. |

0.92 (0.77–1.11)l n.s. |

|

Heart failure-related hospitalisation Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

0.65 (0.50–0.85) p = 0.002 |

0.67 (0.52–0.87) p-value N/A |

0.73 (0.61–0.88) p-value < 0.0018 |

0.70 (0.54–0.90) p-value N/A |

Established cardiovascular disease (CVD) included a history of myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, unstable angina, stroke or peripheral artery disease.

i one-sided P values are shown for tests of noninferiority.

j two-sided P values are shown for tests of superiority

k 95.6% CI

l 95.8% CI

n.s. not statistically significant; N/A statistical analysis not performed or not reported

SGLT2 inhibitor HFrEF efficacy trials

Following the 2019 DAPA-HF trial described above, the 2020 EMPEROR-Reduced trial for empagliflozin in HFrEF was published. The study design was similar to that of the 2019 DAPA-HF trial.37

A 2020 meta-analysis comparing the 2019 DAPA-HF trial and 2020 EMPEROR-Reduced trial found the two medicines were consistent in their cardiovascular effects, reducing the relative risk of heart failure-related hospitalisations and/or cardiovascular death by 25%.44

The clinical evidence and international guidance suggest either dapagliflozin or empagliflozin may be prescribed for people with HFrEF who have LVEF ≤ 40%, alongside other standard treatments – an ACE inhibitor (or ARB or ARNI), heart failure beta blocker and MRA.30-32

References

- Chan YK, Tuttle C, Ball J, et al. Current and projected burden of heart failure in the Australian adult population: a substantive but still ill-defined major health issue. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:501.

- Atherton JJ, Sindone A, De Pasquale CG, et al. National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Guidelines for the prevention, detection, and management of heart failure in Australia 2018. Heart Lung Circ 2018;27:1123-208

- Dunlay SM, Givertz MM, Aguilar D, et al. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and the Heart Failure Society of America: This statement does not represent an update of the 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA heart failure guideline update. Circulation 2019;140:e294-e324

- Atherton JJ, Hayward CS, Wan Ahmad WA, et al. Patient characteristics from a regional multicenter database of acute decompensated heart failure in Asia Pacific (ADHERE International-Asia Pacific). J Card Fail 2012;18:82-8.

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. PBS Schedule: Summary of Changes (January 2022). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2022. (accessed 1 January 2022).

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. PBS General Schedule (December 2021). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2022. (accessed 1 December 2021).

- Australian Medicines Handbook. Dapagliflozin. Adelaide: AMH Pty Ltd, 2021. (accessed 5 November 2021).

- AstraZeneca Pty Ltd. Dapagliflozin (Forxiga) product information. Macquarie Park, NSW: AstraZeneca Pty Ltd, 2021. (accessed 5 November 2021).

- Boehringer Ingelheim Pty Ltd. Empagliflozin (Jardiance) product information. North Ryde, NSW: Boehringer Ingelheim Pty Ltd, 2021. (accessed 19 November 2021).

- Merck Sharp & Dohme (Australia) Pty Ltd. Ertugliflozin (Steglatro) product information. Macquarie Park, NSW: Merck Sharp & Dohme (Australia) Pty Ltd, 2019. (accessed 19 November 2021).

- Australian Diabetes Society. Australian type 2 diabetes glycaemic management algorithm. Sydney: Australian Diabetes Society, 2021. (accessed 19 November 2021).

- Joshi SS, Singh T, Newby DE, et al. Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor therapy: mechanisms of action in heart failure. Heart 2021.

- Thynne T, Doogue M. Sodium-glucose co-transporter inhibitors. Aust Prescr 2014;37:14-6.

- Chesterman T, Thynne TR. Harms and benefits of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors. Aust Prescr 2020;43:168-71.

- Cardoso R, Graffunder FP, Ternes CMP, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors decrease cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalizations in patients with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. E Clin Med 2021;36:100933. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34308311/.

- Sharma A, Pagidipati NJ, Califf RM, et al. Impact of Regulatory Guidance on Evaluating Cardiovascular Risk of New Glucose-Lowering Therapies to Treat Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Lessons Learned and Future Directions. Circulation 2020;141:843-62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31992065/.

- Mannucci E, Dicembrini I, Lauria A, et al. Is glucose control important for prevention of cardiovascular disease in diabetes? Diabetes Care 2013;36 Suppl 2:S259-63.

- McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1995-2008.

- Tsampasian V, Baral R, Chattopadhyay R, et al. The Role of SGLT2 Inhibitors in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiol Res Pract 2021;2021:9927533.

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian Public Assessment Report for Dapagliflozin. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2021. (accessed 8 November 2021).

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Prescription medicines: new or extended uses, or new combinations of registered medicines. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2021. (accessed 8 November 2021).

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Public Summary Document: Dapagliflozin (September 2021 PBAC Meeting). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2021. (accessed 24 December 2021).

- Burnett H, Earley A, Voors AA, et al. Thirty years of evidence on the efficacy of drug treatments for chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a network meta-analysis. Circ Heart Fail 2017;10:e003529.

- Cardiovascular Expert Group. Therapeutic Guidelines: Heart failure. East Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd 2018. (accessed 29 October 2020).

- National Heart Foundation of Australia. Pharmacological management of chronic heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFrEF). Melbourne: NHF, 2019. (accessed 28 October 2020).

- Sindone AP, Haikerwal D, Audehm RG, et al. Clinical characteristics of people with heart failure in Australian general practice: results from a retrospective cohort study. ESC Heart Fail 2021.

- Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2117-28.

- Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. Dapagliflozin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019;380:347-57.

- Cannon CP, Pratley R, Dagogo-Jack S, et al. Cardiovascular Outcomes with Ertugliflozin in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1425-35.

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3599-726.

- McDonald M, Virani S, Chan M, et al. CCS/CHFS Heart Failure Guidelines Update: Defining a New Pharmacologic Standard of Care for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. Can J Cardiol 2021;37:531-46.

- Maddox TM, Januzzi JL, Jr., Allen LA, et al. 2021 Update to the 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for Optimization of Heart Failure Treatment: Answers to 10 Pivotal Issues About Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:772-810.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dapagliflozin for treating chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2021. (accessed 23 November 2021).

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Prescription medicines: applications under evaluation. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2021. (accessed 20 December 2021).

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. PBAC Outcomes: Recommendations made by the PBAC (November 2021). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2021.(accessed 17 December 2021).

- Novartis Pty Ltd. Sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) product information. Macquarie Park, NSW: Novartis Pty Ltd, 2020. (accessed 23 November 2021).

- Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1413-24.

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Public Summary Document: Dapagliflozin (July 2021 PBAC Meeting). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2021. (accessed 16 November 2021).

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. PBAC Outcomes: Recommendations made by the PBAC (September 2021). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2021. (accessed 27 December 2021).

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Public Summary Document: Dapagliflozin (November 2020 PBAC Meeting). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2020. (accessed 9 November 2021).

- AstraZeneca Pty Ltd. Dapagliflozin (Forxiga) consumer medicine information. Macquarie Park, NSW: AstraZeneca Pty Ltd, 2021. (accessed 9 November 2021).

- Yan Y, Liu B, Du J, et al. SGLT2i versus ARNI in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ESC Heart Fail 2021;8:2210-9.

- Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al. Canagliflozin and Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017;377:644-57.

- Zannad F, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a meta-analysis of the EMPEROR-Reduced and DAPA-HF trials. Lancet 2020;396:819-29.